Barely a month after crowds outside the Pennsylvania State House cheered the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence “a Black Lad” named George Samba made his own bid for independence. In Wapping, on August 12, this fourteen-year-old African escaped from his master’s home on Bird Street, today known as Tench Street, lying a couple of blocks north of Execution Dock in London’s East End. Samba spoke “good English” and so presumably had been on British ships or in Britain for some time, but he was “a native of the Pool nation, in Senegal.” This is quite possibly a reference to the Pular or Fula language, a Senegambian language spoken in various dialects across a broad swath of West Africa, but in this case perhaps referring to the region around the Senegal and Gambia rivers. Later in the history of the Transatlantic slave trade males from this region were recorded with names such as Samba and Sambah, and so perhaps this Senegalese boy had been able to keep his own name and use it in conjunction with the English name George.[1]

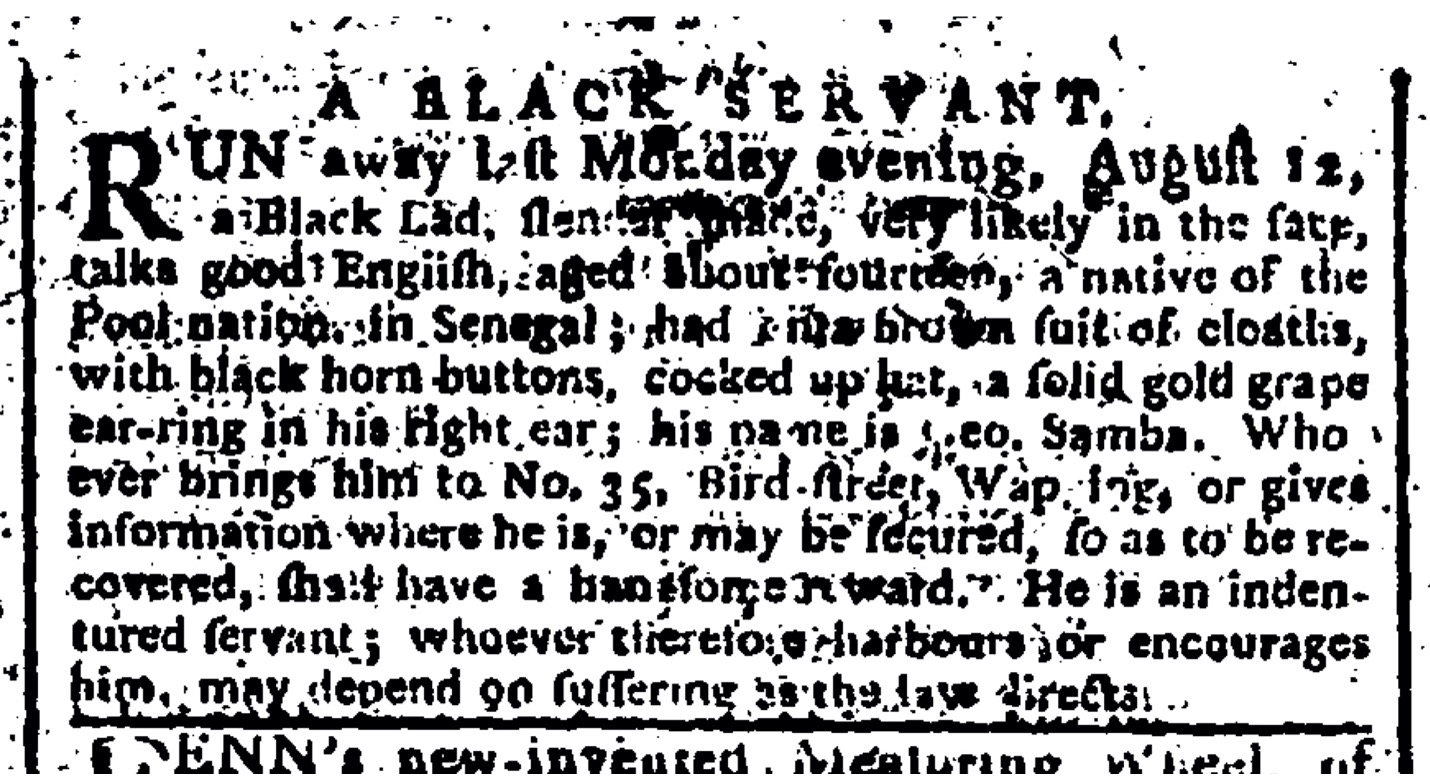

George Samba was identified in this advertisement as “A Black Servant” and “an indentured servant,” so although he almost certainly had been enslaved earlier in his life and had endured the Middle Passage, he was now in a liminal state between racial slavery and the servitude of young White Britons. He was well dressed, suggesting he worked as the personal attendant of a wealthy man, and he wore a livery or uniform of “a brown suit of cloaths, with black horn buttons, [and a] cocked up hat.” Samba also wore “a solid gold grape ear-ring in his right ear,” and he was better dressed than many of London’s White servants. Yet despite all of that he clearly wanted to free himself from the master who was not identified in this short newspaper advertisement. Samba could be returned for “a handsome reward” to Number 35, Bird Street, Wapping.

The newspaper advertisement describing Samba and offering “a handsome reward” for his recapture and return reveals little of his interior life and does not even identify his master. He appears to have lived and worked in the heart of London’s East End amongst those who equipped and manned the ships carrying enslaved Africans and the crops they produced, and it seems clear that he thought that escape was his best path to meaningful freedom. In general the masters of White servants who eloped before the end of their contracted terms of service did not advertise for or offer rewards for their capture, unless they had stolen property when they eloped. By advertising for and offering a reward for the return of George Samba, his master indicated his own belief that Samba was less free than White servants, perhaps helping us to understand why Samba was determined to fully free himself.

Escaping in 1776 gave George Samba great opportunities to find new employment as a nominally free man. The advent of a large imperial war, and the recruitment of boys and men to both the army and navy offered him the opportunity to join up, or to use the chaos as cover for an escape. The army regularly advertised for new recruits, offering a shorter three-year term of service as well as a bounty of one-and-one-half guineas. Between spring of 1775 and 1776 the Royal Navy set about increasing the number of seamen from 16,000 to 28,000, and thereafter the number increased significantly, as did the number of merchant sailors and privateers. The British army increased in size too, with almost 20,000 new British recruits in the two years from 1775, again increasingly significantly once France entered the war. For the Royal Navy and the merchant navy in particular, the employment of Black mariners “was an essential component to Britain’s military successes.” Military service was harsh, and Black soldiers and sailors did not enjoy all of the benefits potentially available to Whites. But there was a rough equality amongst the sailors and soldiers who depended upon one another, and Olaudah Equiano wrote with real affection about his time as a sailor, and his relations with White crewmates. Perhaps George Samba was one of the enslaved people on both sides of the Atlantic who were able to escape their masters by joining the British military or merchant marina in the war against American independence.[2]

View References

[1] African Names Database, Slave Voyages, https://www.slavevoyages.org/resources/downloads#african-names-database-downloads/0/en/ (accessed March 17, 2022). See, for Example, the name Samba listed for voyages 2319 and 2898, and the name Sambah listed for voyage 3013.

[2] Charles R. Foy, “The Royal Navy’s employment of black mariners and maritime workers, 1754-1783,” The International Journal of Maritime History, 28, no.1 (2016), 8. For an example of a recruiting notice see “War Office, December 16, 1775. It is His Majesty’s Pleasure…,” recruiting announcement in the London Gazette, December 16, 1775. See also Stephen Conway, The British Isles and the War of American Independence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 13-15; Edward E. Curtis, The Organization of the British Army in the American Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1926), 54-6. For Equiano see Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings, ed. Vincent Carretta, (New York: Penguin, 2003), 62-94.