The days were shortening in 1733, and the chill of winter tightening its grip on Boston, when Letitia found a visitor on the stoop. Letitia at the time might have been seven, the age at which children began to be considered useful in New England, or perhaps she was a bit older—ten or so.[1] A girl of African ancestry, she was enslaved by James Gordon, a wealthy merchant in town. As for the visitor at the door, she was a free white woman, a neighbor named Mary Butler. Mary showed up that winter not once, not twice, but “several times.” And each time she brought with her the same request. The wife of a saddler named Samuel Butler, and a new mother of twins, Mary came for Letitia. Again and again, she asked James’s wife to “let her have her Negro girl Lattice to serve her.”[2]

Letitia likely began to dread hearing the women parley over her future by the hearth. But the Gordons, for their part, persistently denied Mary’s request. Perhaps Letitia’s labor was needed in their household. Or maybe Letitia made it clear to her enslaver that she did not wish to go. Months passed. The snow melted, the ground thawed, and Mrs. Gordon’s kitchen garden—likely tended by Letitia—began to bear the season’s first peas and lettuces. Only then did the Gordons relent. In June of 1734, Letitia bade farewell to Prince and Affey, companions of African descent who worked alongside her in the Gordon home, and she went to serve the Butlers.[3] Within two years, however, Letitia was back, as the Gordons and the Butlers could not agree on how much money ought to be paid for her labor.[4] Then, a year and a half after that, James sent Letitia away again—this time, according to the bill of sale, for good.

Letitia was sold to a Boston shopkeeper named John Wass. She was still referred to as a “girl” in the document that deeded her to John, but now she was an older one, perhaps between 12 and 15 years.[5] And she had become valuable as values were reckoned in slave-trading societies: James pocketed 120 pounds from the transaction, a sum that exceeded the average price paid for grown men in the region.[6] Was Letitia especially physically attractive? Unusually hard-working? Literate and capable of helping to run John’s shop? Perhaps she had developed a robust suite of domestic skills when working for the saddler’s wife. Whatever the reason, John was willing to pay dearly to bring Letitia to his household.

John’s household, however, was not one in which Letitia wished to live.

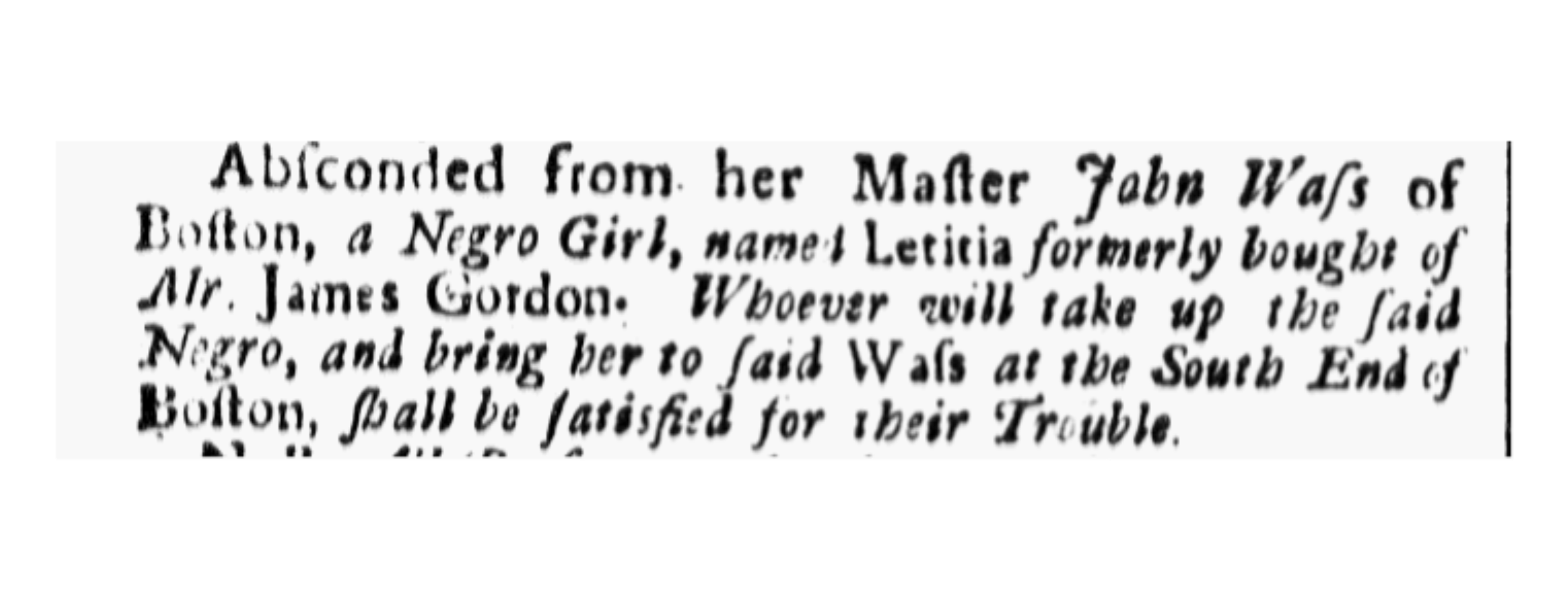

Eventually, Letitia left. Hers was not an escape shrouded in mystery: John knew precisely where she had gone. Consider the advertisement he posted in April, 1739 in attempt to reclaim her. Besides stating Letitia’s name and describing her as a “Negro Girl,” it mentioned only one other bit of information about her: that she was “bought of Mr. James Gordon.” The elaborate descriptions which fill freedom-seeker notices—of clothing, appearances, mannerisms, skills, origins, and linguistic capabilities—are missing entirely. John needed to do just one thing in order to ensure Letitia’s recapture: associate the girl with James. For Letitia had returned to the Gordons.[7]

Determined to punish the Gordons for the girl’s escape, the aggrieved shopkeeper soon filed a lawsuit against James. John claimed that he had “lost” Letitia and James had “found” her, speaking about the girl as if she were an object that had been misplaced—or, perhaps, an ignorant beast: a cow that had strayed from the herd or a sheep that had lost its way.[8] But Letitia, for her part, knew exactly where she was. She had lived in Boston for at least the past six years, and she was intimately familiar with the neighborhood. Letitia had not gotten lost; she had made a conscious decision to leave.[9]

Why had Letitia abandoned her present enslaver for her former one? Depositions filed in court reveal that the girl was sick, grievously so, and that she attributed her ailments to mistreatment in the Wass household. A neighbor recalled in graphic detail the extent of Letitia’s suffering. She “sett down in our Kitchin without saying anything for a Considerable time, being almost Choak’d w[i]t[h] a Violent fit of Coughing.” Letitia vomited as well—this, too, was described as “Violent”—and she had lost her appetite almost entirely; as the neighbor put it, Letitia had “scarce any stomach at her Victuals.”[10] She was described by another as “much emaciated” with a “violent cough”: a girl in a state of “genuine consumption.”[11]

When a neighbor asked Letitia how long she had suffered from her racking cough, the girl answered a “good while,” and she explained that she had “been Ill ever Since her M[ist]r[es]s Cut off her Wool.”[12] Letitia apparently was victim of the forcible bodily manipulation that enslaved people suffered in many times and places. John’s wife had shaved the girl’s hair, clearly against her will. And this maltreatment, as Letitia saw it, had consequences that went beyond physical appearance: The shearing had made Letitia dangerously ill.[13]

When the ailing girl showed up on the Gordons’ stoop, her former enslaver summoned a doctor in hopes of treating her. Letitia, though, remained trapped by the fact of John’s ownership. The doctor refused even to dispense advice because he did not have the permission of the girl’s “Proper Master.”[14] And though the Gordons made an effort to hide Letitia in their house, secreting her in an “upper Chamber,” Letitia was forced back to the Wass home before the end of April. A heartbreaking deposition recalled that the girl was “afraid” to go in upon her return, and that her old comrade Prince had to beg John on Letitia’s behalf “not to beat her” for absconding.[15]

Head shorn, lungs bloodied, and body wasted, Letitia did not live long in the Wass household. By July, her lifeless body lay in an area burial ground.[16]

If anyone memorialized the place of her interment—Prince, perhaps, or Affey, or maybe the Gordons—their marker does not survive.

View References

[1] See Ruth Wallis Herndon, “‘A Proper and Instructive Education’: Raising Children in Pauper Apprenticeship,” in Children Bound to Labor: The Pauper Apprentice System in Early America, eds. Ruth Wallis Herndon and John E. Murray (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009), 15. See also Gloria McCahon Whiting, Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Freedom in Early New England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2024), chap. 3.

[2] Deposition of Keziah Passloe, Suffolk Files case 53169, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston.

[3] Gordon v. Butler, Suffolk County Court of Common Pleas, vol. 1740, 144, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston.

[4] Gordon v. Butler, Suffolk County Court of Common Pleas, vol. 1740, 144–145.

[5] Bill of Sale, Suffolk Files case 51176, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston.

[6] In 1737, the year Letitia was sold, the average enslaved man appraised by Suffolk County’s probate court was valued at less than 120 pounds. For two examples of inventories valuing men, see John Welland’s inventory, 1737, Suffolk County Probate Court, First Series, vol. 33, 389, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston and Jacob Williams’s inventory, 1737, Suffolk County Probate Court, First Series, vol. 33, 136, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston.

[7] “Absconded from her Master,” Boston Gazette, Apr. 2, 1739.

[8] Wass v. Gordon, Suffolk County Court of Common Pleas, vol. 1739, 231, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston.

[9] Cases arguing that bondspeople were “lost” and then “found” proliferate in Massachusetts court records, and the bondspeople at their center seem regularly to have chosen to desert one enslaver for another. For more on the application of language dealing with strayed livestock to people in New England, see Gloria McCahon Whiting, Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Family in Early New England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2024), chap. 5. See also Holly Brewer, “Creating a Common Law of Slavery for England and its New World Empire” Law and History Review 39 no. 4 (November 2021), 765–834.

[10] Deposition of Kezia Passloe, Suffolk Files case 51176, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston.

[11] Deposition of William Douglass, Suffolk Files case 51176, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston. Letitia likely was suffering from tuberculosis, which regularly was called “consumption” at this time due to the wasting effect it had on the body.

[12] Deposition of Kezia Passloe, Suffolk Files case 51176.

[13] For the shaving of enslaved people’s heads as a punishment or out of spite, see Shane White and Graham White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries” Journal of Southern History 61 no. 1 (February 1995), 49, 68–69. For what appears to have been the opposition of Black women to shaving their heads in North America during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, see White and White, 54.

[14] Deposition of William Douglass, Suffolk Files case 51176.

[15] Deposition of Mary Butler, Suffolk Files case 51176, Massachusetts State Archives, Boston.

[16] Deposition of Mary Butler, Suffolk Files case 51176.