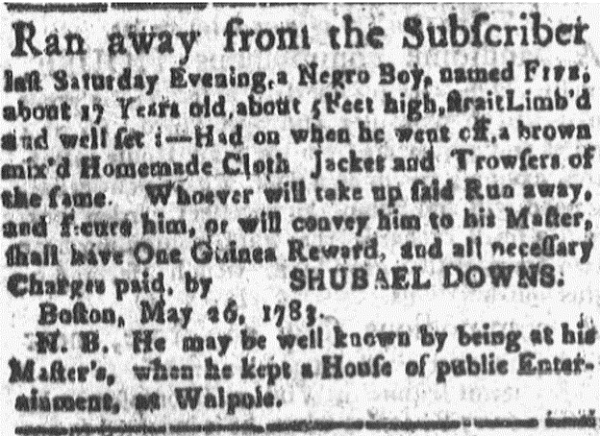

Peculiar indeed is the politics of naming. In a time in which men and women owned other men and women as property, as a simple-minded beast of burden, naming signified power. In the minds of those who were subject to its prerogative, naming represented the ultimate expression of a master’s control over his or her people. Indeed, the privilege of naming, Orlando Patterson reminds us, is “a symbolic act” that strips “a person of his former identity.” While the significance of the new name would vary from one slave culture to the next, they all had one thing in common. “The slave’s former name died with his former self.” Naming signaled, in the most direct way, the transformation of a human being into a thing. That was truly the case of a “Negro Boy, named FIVE” whose story appeared in print in the pages of the Boston Gazette in 1783.[1]

Compared to his counterparts in the mid-Atlantic and southern colonies, Five’s master, a New England mariner and grandee in his own right, appeared no less invested in exercising his rights over his property.[2] Well before the lad had even been born, most New England enslavers, like those elsewhere, had already adopted a practice in which they reserved particularly impersonal names like Goree, Planter, Hazzard, Boatswain, or Sharper for individual captives recently imported from Africa. The same was likely true of Shubeal Downs’ boy. Before the emergence of native-born Black communities, enslavers also routinely named slaves after port cities like London or Boston or figures in classical mythology. Amid notices for missing horses and lots of land for let were numerous advertisements for freedom seekers named Cesar or Cato. If not names like Hercules, Cicero, or Chloe, New England enslavers forced their bondservants to take diminutive names like Tom instead of Thomas, Dick as opposed to Richard. In this setting, Five’s name might disclose something of the “17 Year old” boy’s background.[3]

That had certainly been true in the case of Venture Smith. Brought from Africa to America sometime in 1739, the son of the Prince of Dukandarra arrived in Rhode Island abroad a tight packed vessel whose voyage across the Atlantic marked the beginning of his transformation from a member of an African royal family into a slave. By Broteer’s account, he was purchased on board a slave ship by one Robertson Mumford. In exchange for “four gallons of rum” and “a piece of calico,” the captain’s mate took possession of the young boy and named him “Venture” on account that he deemed the transaction a successful one.[4]

Similarly, in his autobiography, Olaudah Equiano would suffer the indignity of the politics of naming on more than one occasion. By his own account, he had been named and renamed several times. Before he would eventually arrive in Virginia, he had been named twice by his captors; first Jacob, then Michael. In both instances, he had been named for figures in the Bible. Later, however, when he became the property of Michael Pascal, he would be renamed Gustavus Vassa. At first, Equiano refused the name and expressed his preference for the name Jacob. Muffed by the enslaved man’s brazen act of insolence, the mariner placed the African in chains until he relented.[5]

Five’s name might also conceal a similar origin story. The property of a mariner, he too, might have come by his name under peculiar circumstances. Whether on board a slave ship or somewhere else, Downs may have given him the name because he might have been the fifth person he had purchased. Or he might have been the fifth piece of property in a larger business transaction. Either way, with as little regard as it appears that Broteer or Equiano had been named, the same appears to be true of Five’s master. More so than his physical description or the articles of clothing he stole away with, his name tells a tragic story.

Interestingly, while Venture Smith and Gustavus Vassa would elect to stay put, Five did not. His name denoted not only his status as a slave, but also something of the harsh treatment he might have received at the hands of his master. That is to say, Five had had enough. Clearly, he wanted to be his own master. To that end, he took matters into his own hands and protested slavery with his feet. For several days, if not longer, he owned himself. In all likelihood, he assumed for himself another name, one that did not reflect anything of his former master.[6]

View References

[1] Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982), 55.

[2] Several years before he purchased Five, the mariner had been the master of at least two bondservants: a poor child named Peter Bout (October 15, 1768) and a poor boy by the name of William Akley (October 6, 1774). The extant indentures for both servants show indenture servitude as a peculiar institution akin to what Orlando Patterson characterized as a form of social death in which bondservants were rendered as a type of cattle who enjoyed few privileges. https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:zs25xb162; https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:1c18dq02z.

[3] Before emancipation, names signified complex stories not only of resistance, agency, and cultural retentions, but also violence and accommodation.

Naming characteristics of New England runaways (measured in percentages).

Naming categories

Periods African Biblical Classical Work-Geo Anglo n/a

1730s 27% 20% 15% 5% 21% 12%

1740s 20% 15% 29% 13% 16% 7%

1750s 18% 15% 29% 10% 20% 8%

1760s 13% 22% 23% 13% 20% 9%

1770s 9% 13% 26% 14% 28% 10%

Sources: Lathan A. Windley, Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History. New York: Greenwood Press, 1983. 4 vols; Billy G. Smith and Richard Wojtowicz, Blacks Who Stole Themselves: Advertisement for Runaways in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728–1790. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989; Graham Russell Hodges and Alan Edward Brown, ‘Pretends to Be Free’: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial and Revolutionary New York and New Jersey. New York: Fordham University, 1994; Antonio T. Bly, Escaping Bondage: A Documentary History of Runaway Slaves in Eighteenth-Century New England, 1700–1789. Maryland: Lexington Books, 2012; Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers Database; and, Eighteenth-Century American Newspapers in the Library of Congress in Microfilm.

[4] Venture Smith, A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture, a Native of Africa: But Resident above Sixty Years in the United States of America. Related by Himself. New London: C. Holt, 1789.

[5] Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by Himself (London, 1789), 1: 93–6. Billah, whose story is the subject of another Freedom Seekers story, proved the exception to this rule.

[6] Incidentally, news of what would become the Quock Walker cases, that led to the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts, might have inspired Five to run away as well. Robert M. Spector, “The Quock Walker Cases (1781-1783): Slavery, Its Abolition, and Black Citizenship in Early Massachusetts” Journal of Negro History 53.1 (January 1968): 12-32.