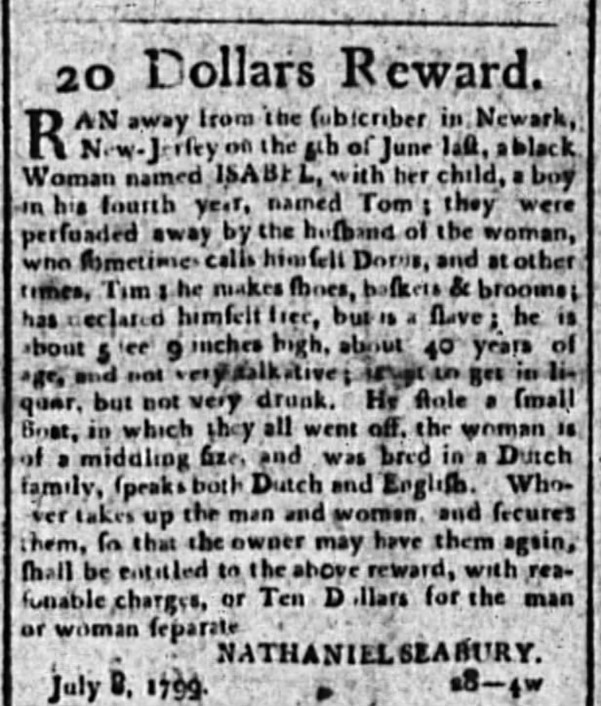

There are tens of thousands of enslaved runaway advertisements in the classified columns of New World newspapers. They are shards, relics from two centuries and more ago. Compressed, factual, and fleeting, these advertisements reveal something of not just enslaved life but perhaps, as was quite possibly the case with Isabel and family, the vital and defining moment in that life. They were intended to help identify and recapture enslaved men and women who had escaped—the most informative of them contain the bare bones of the story of an African American life that, sometimes, we can flesh out. And for that these postcards from the past are all the more moving. Often the material is so vivid that emotional engagement is called for and inevitable. Who now can read Nathaniel Seabury’s advertisement in the Poughkeepsie Journal and not cheer on Isabel, Dorus and Tom as they slipped away, stole a boat and lit out for the territory?

Finds such as Seabury’s advertisement used to be so hard-won, the fruit of countless hours in a library. Even as I write this, it is forty-five years since my first encounter with these advertisements. One Australian summer, as a twenty-year-old working on my honors thesis, I read all extant issues of South Carolinian newspapers published between 1740 and 1770 and copied out every runaway advertisement.[1] It was where and when I found my intellectual feet. Over much of the ensuing decade as a graduate student I similarly pored over New York newspapers, dozens of different titles.[2] Those days are long gone and things are much easier. First came various compilations of runaway advertisements where someone else had collected and published hundreds of these notices.[3] And then digitally searchable newspapers arrived. The South Carolinian material that I collected over three months of very hard work all those years ago, today’s honors student could gather in a matter of minutes. And they could do it from their desktop computer sitting at home.

It would be foolish to deny that a revolution has occurred in the way we find out about the past and that historical research is often a much easier affair than it used to be—and I know it is hackneyed to harp on about it, but something also has been lost. Old-fashioned as it may seem, reading newspapers discolored with age—reveling in their feel, smell and appearance, being distracted by surprising stories about this and that which often turn out to be more important than what you were looking for—remains, to my mind, one of the pleasures of being an historian. Now the New York libraries I use have most of their bound volumes of newspapers in storage somewhere in New Jersey or, god help us all, deep in western Massachusetts. Perusing column after column of classifieds, looking for runaway advertisements and then painstakingly typing out or copying hard-won nuggets is a rather different experience from having a computer present them to you instantaneously. I don’t mean to sound like a Luddite, decrying the plane and advocating the virtues of the train for the trip from New York to San Francisco. Digitally searchable sources are, to anyone who has done time in a research library, a technological wonder. But the old-fashioned route did promote a different perspective on the world. Fossicking, with more often than not a long hiatus between finds, and above all transcribing prompted the historian to reflect on her sources. Still, to this day, I have to type out all my sources preparatory to writing anything. Copying, at least for me, is an essential component of being an historian, inseparable from thinking about the past.

Part of the allure of the advertisements as a source is that they do require reflection if we are to tease out additional meaning from the laconic wording of the enslavers. Note the date of the escape of the slaves Seabury claimed were still his property. Early June 1799 was between the passage of New York’s “An Act for the gradual abolition of Slavery” in late March 1799 and July 4, the date the measure came into effect. This law did not apply to Dorus. It only freed, and then in a limited fashion, the children of slaves born after July 4, 1799. The legislature had simply abandoned to their fate anyone unfortunate enough to be a slave on July 4, as was the case with Dorus. And of course, although Newark, where he was enslaved, fell within Manhattan’s orbit, it was in New Jersey not New York—whatever laws the New York legislature enacted were not intended to have any effect on Dorus’ life. Not that any of these details mattered one whit. With the passage of the gradual abolition measure, somewhere in the universe a gear had shifted and an infectious belief in the possibility of freedom was spreading among the enslaved. No one caught up in the enthusiasm was paying any attention either to legal fine print or to the location of the boundary separating New York from New Jersey. It was now inevitable that slavery was going to end north of the Mason and Dixon Line and this changed forever the relationship between enslaver and enslaved in and around New York City. Over the ensuing three decades or so individual enslaved men and women did their best to exploit the way the old certainties of slavery were crumbling in order to negotiate—or to seize—a better life for themselves.

Dorus had staked his claim for freedom right at the beginning of this liminal period as slavery transmuted stutteringly into freedom. It was a time of uncertainty. Owners faced the threat of losing their property with little or only partial recompense but for the enslaved it burst with possibility. Seabury’s wording is telling: Dorus had “declared himself free, but is a slave.” In a slave society—and roughly four out of every ten households living within fifteen miles of New York City possessed at least one African American in the 1790s[4]—an enslaved man simply announcing that he was free and no one owned him anymore was a harbinger of how messy slavery’s demise would be in this area. Seabury’s enslaved man’s aggressively pre-emptive declaration of freedom had taken him by surprise. Perhaps he almost acquiesced. In the first few lines of the advertisement he almost seemed to accept Dorus’s self-liberation.

Seabury’s advertisement also underlined the importance of Dutch culture in and around New York City. The Dutch, long settled in the Hudson River Valley, western end of Long Island, much of New Jersey and New York City itself, were heavily involved in slavery, and the influence of their culture lingered. It was not unusual even in the early nineteenth century to find enslaved African Americans who could speak only Dutch; many more were bi-lingual, conversant in both Dutch and English. As with many of her compatriots, Isabel had been “bred in a Dutch family, speaks both Dutch and English.” Here what is revealing is Dorus’s name. Perhaps at first sight he appears to be named after the Greek mythological figure of Dorus, son of Hellen and founder of the Dorian nation. There was almost no end to enslavers’ jocularity when it came to the nomenclature of the enslaved. Any number of unfortunates were lumbered with classical or other “humorous” names thanks to some perverse whim of their owner. A “Negro Man” who celebrated Independence Day by decamping from his owner in Westchester County on July 4, 1816, was “named BRAVEBOY, but calls himself Martin.”[5] The passive “named” followed by the active “calls himself” gives a fair indication of the tension between enslaver and enslaved’s differing perspectives on the world. Seabury’s former enslaved man, though, chose to use both Dorus and Tim. As it turns out, “Dorus” also was a not unusual Dutch abbreviation of “Theodorus.” Isabel and Dorus may have been owned by the Anglo Seabury, but, more likely than not, they had been raised in and shaped by the African Dutch culture still obviously a powerful presence in New York’s hinterland.

That background also helps to make sense of why Seabury placed his advertisement in the Poughkeepsie Journal—Poughkeepsie is some seventy miles away from Newark. Chances are that when this family pushed their stolen boat off from the shore near Newark and lit out for the territory, that territory was the Dutch stronghold on the left bank maybe a few score miles up the Hudson River. That certainly seems to have been their former owner’s expectation. If Nathaniel Seabury had been somewhat taken aback by Dorus’ own declaration of independence, he regathered himself and did not just shrug his shoulders and resign himself to the loss of his property. In ways that presaged race relations in and around New York City for decades, Seabury wanted things to stay the same and went to some effort to regain possession of what he thought of as his rightful property. On the other hand, African Americans insisted on change, most particularly they sought desperately to become free as quickly as possible, certainly earlier than any legislature intended. Struggles over the unresolved differences between Black and white views of the meaning of slavery and expectation of what freedom meant—often the gap was more of a chasm—would cast a long shadow over race relations down at least as far as the Draft Riots of 1863.

Thousands of names of the unknown enslaved, as well as those of their not nearly as anonymous owners, do live on, momentarily, in runaway advertisements buried in the endless columns of classifieds in newspapers. But it is the most fleeting and ephemeral of existences. If occasional runaway advertisements reveal the bare bones of an enslaved person’s story most were fragmentary and laconic. It is a spare minimalist genre—more haiku than epic poem. That is one of the frustrations of these notices as a source for historians, as well as part of their charm. We have no idea what happened to Isabel, Tom and Dorus.

View References

This piece is adapted from my article “The Allure of the Advertisement: Slave Runaways in and around New York City,” Journal of the Early Republic, 40 (Winter 2020): 611-33.

[1] Part of the honors thesis was eventually published as Shane White, “Black Fugitives in Colonial South Carolina,” Australasian Journal of American Studies, 1 (July 1980), 25-40.

[2] My PhD thesis was published as Shane White, Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City, 1770-1810 (Athens and London: University of Georgia Press, 1991).

[3] Most obviously, see Lathan A. Windley, Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History from the 1730s to 1790 (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1983 (4 vols)). But for the purposes of this piece, see Graham Russell Hodges, “Pretends to Be Free”: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial and Revolutionary New York and New Jersey (New York: Garland Publishing, 1994); Susan Stessin-Cohn and Ashley Hurlburt-Biagini, In Defiance: Runaways from Slavery in New York’s Hudson River Valley, 1735-1831 (Delmar, NY: Black Dome Press, 2016).

[4] On slaveholding in and around New York City, see White, Somewhat More Independent, 16.

[5] New York Herald, July 27, 1816.