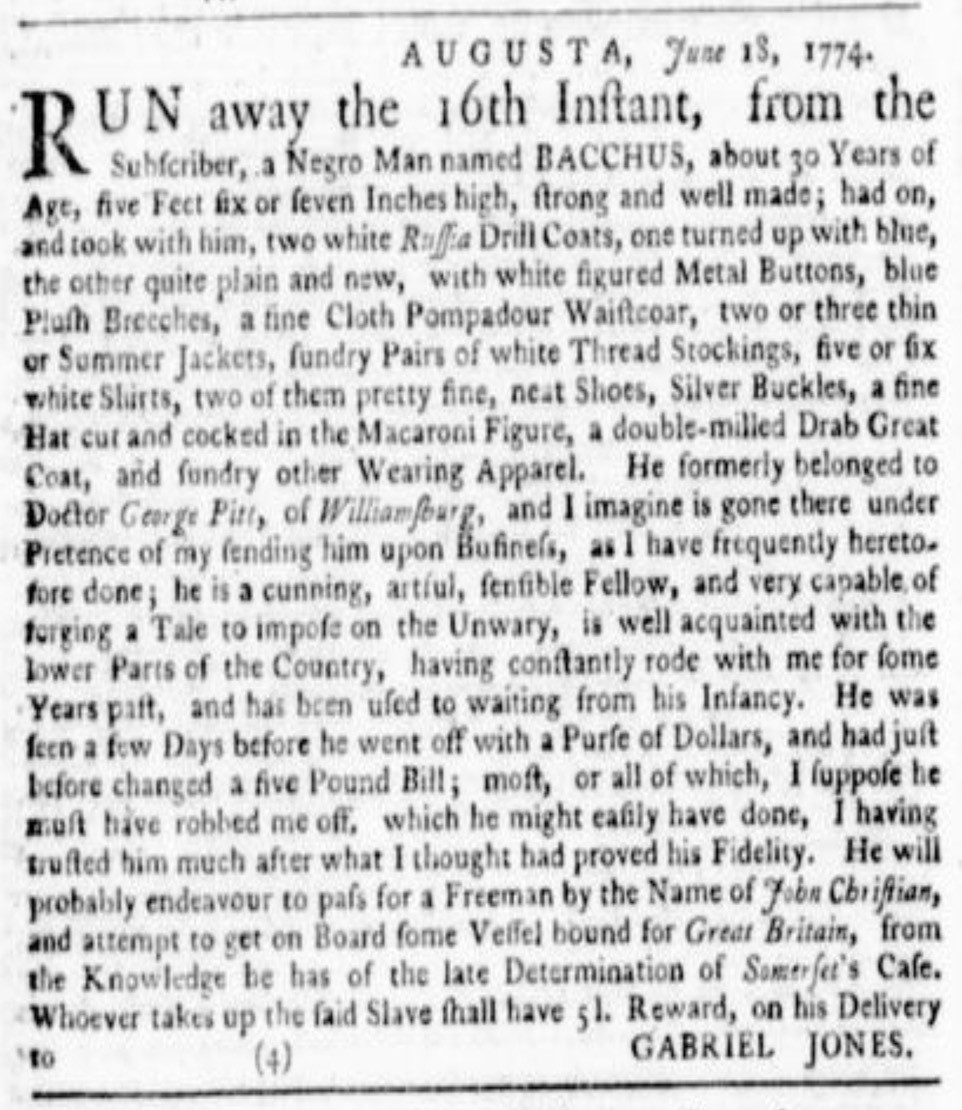

What did the landscape of freedom look like to enslaved people seeking to escape bondage on the eve of the American Revolution? Where in the Atlantic world did runaways think they could find freedom? In the eyes of Bacchus, “a cunning, artful, sensible Fellow” about thirty years old who ran away from his owner in the summer of 1774, liberation could be found across the ocean in England, where the highest court had recently declared in the 1772 Somerset v. Stewart ruling that enslaved people who arrived in Great Britain could not be taken back to the colonies against their will, a decision widely interpreted as providing sanctuary to freedom seekers from the colonies.[1]

Until the Somerset ruling, the legal concept of “free soil” did not exist—not just in the British Atlantic but indeed anywhere in the Atlantic world. Slavery was legally sanctioned throughout the western hemisphere until the northern states of the United States began to abolish slavery gradually during the American Revolution and its aftermath (between 1777 and 1804, depending on the state). The popular strategy of running to “northern free soil,” employed by American runaways from the US South in the nineteenth century, was unavailable to runaways like Bacchus, for the simple reason that “northern free soil” did not exist in 1774. What did exist, at least since the Somerset ruling, was the perception of free soil in England.[2]

Somerset v. Stewart revolved around the status of an enslaved man from Boston named James Somerset, who had been brought to England in 1769 by his owner, Charles Stewart. Two years later, in 1771, Somerset absconded. When he was caught, Stewart had him imprisoned on board a ship bound for Jamaica, with instructions for his enslaved man to be sold there for plantation labor. Somerset’s godparents in England enlisted the help of an abolitionist attorney, who sued for Somerset’s freedom, arguing that he had become free upon arrival in England. In his final ruling, the chief justice, Lord Mansfield, declared that slavery in England had no basis in either “natural law” or “common law,” and that it therefore required a statute passed by Parliament to legitimate it. As such a statute did not exist, Mansfield ruled that Somerset could not be forced to leave Britain for renewed slavery in the colonies, and ordered him discharged. Although technically limited—the Mansfield decision did not necessarily end slavery in Britain—the Somerset ruling was widely interpreted as upholding the principle that enslaved people became free upon arrival in Britain. It caused a sensation in the colonies, especially in North America, where a rebellion against British rule was already brewing and where slaveholders now widely feared that Parliament would start to interfere with slavery in their colonies. To enslaved people, however, the Somerset case seemed to create new opportunities for escape. It linked British soil with freedom in the minds of the enslaved, and by extension turned the merchant ships docked at American harbors into potential vehicles to freedom.[3]

Freedom in England appears to have been Bacchus’ ultimate plan, at least according to his owner, Gabriel Jones—a well-known Virginia lawyer and Patriot politician—who placed this advertisement in the Virginia Gazette some twelve days after Bacchus went missing. Jones apparently had good reason to believe that Bacchus would “attempt to get on Board some Vessel bound for Great Britain, from the Knowledge he has of the late determination of Somerset’s Case.”[4] Information networks transmitted news through slave communities like wildfire, especially news of monumental decisions regarding slavery like the Somerset case. It is hardly surprising that Bacchus knew about the case and understood its consequences. The question is how he intended to reach England. Ship captains of merchant vessels docked throughout the Chesapeake Bay—or anywhere else in the colonies—were explicitly prohibited from transporting enslaved people, certainly those who had run away from their owners. Bacchus could hardly present himself as a runaway to a random ship captain and plead to join him on his transatlantic journey. Moreover, he had escaped from Augusta County and was presumed to be making for Williamsburg, a distance of some 275 kilometers (about 170 miles). He had to traverse much of the colony—the largest slaveholding colony in mainland North America—without being taken up as a runaway just to reach a ship in the first place.

Jones believed that Bacchus was traveling across the colony in broad daylight by disguising his true identity and intentions—in short, by passing for someone he was not. Either he was pretending to be traveling “under the Pretence of my sending him upon Business,” as he was “very capable of forging a Tale to impose on the Unwary,” as Jones surmised—or, more interestingly, he was “endeavour[ing] to pass for a Freeman by the Name of John Christian.”[5] The latter strategy—commonly employed by runaways throughout the colonies—entailed a kind of theater. By changing his name and pretending to be a free Black man, Bacchus could hope to travel unmolested throughout the colony and reach the ports of the Chesapeake, essentially achieving freedom in practice, even in the midst of slavery, long before reaching British soil. Passing for free was no easy feat, certainly not in Virginia, where the free Black population constituted less than one percent of the colony’s Black population and where Black people on the roads were regularly stopped on suspicion of being runaways. If Bacchus was going to convince people he was free, he was going to have to look and act free. He needed to have a plan.

He apparently had one, as he escaped with fashionable clothes that were far removed from the coarse garb worn by enslaved people, including “two white Russia Drill Coats”; a “fine Cloth Pompadour Waistcoat”; “neat Shoes [with] Silver Buckles”; and a “fine Hat…cocked in the Macaroni Figure.” Bacchus meant to travel looking like a free man, and a well-dressed one at that. Donning the finest clothes, “John Christian” hardly looked like an enslaved person—at best a personal valet, but he more likely gave the impression of being free. He also took with him a purse of money, stolen from Jones, to sustain himself on his journey, however long it might take.[6]

Bacchus’ networks were important elements of his escape strategy. Jones believed him to be making his way to Williamsburg, where he had previously lived and where he undoubtedly had family or friends who could help provide him with useful information and possibly harbor him until he could put his plan into effect. Disguised as a free man, Bacchus—or “John Christian”—presumably intended to hire his labor to a departing vessel and work his way across the Atlantic to freedom. Whether he made it is unknown, as he subsequently disappears from the historical record. A daring and heroic escape it would have been, however.

View References

[1] “Run away the 16th Instant,” Virginia Gazette, June 30, 1774.

[2] Sue Peabody and Keila Grinberg, “Free Soil: The Generation and Circulation of an Atlantic Legal Principle,” Slavery & Abolition 32 (3) (2011), 331-339; Alan Taylor, American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804 (New York: Norton, 2016), 118-119; Damian Alan Pargas, Freedom Seekers: Fugitive Slaves in North America, 1800-1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), 7-9.

[3] Peabody and Grinberg, “Free Soil,” 331-339; Taylor, Atlantic Revolutions, 118-119; Edlie L. Wong, Neither Fugitive Nor Free: Atlantic Slavery, Freedom Suits, and the Legal Culture of Travel (New York: NYU Press, 2009), 20-22; George Van Cleve, “Somerset’s Case and Its Antecedents in Imperial Perspective,” Law and History Review, 24 (2006), 601-46.

[4] “Run away the 16th Instant,” Virginia Gazette, June 30, 1774.

[5] “Run away the 16th Instant,” Virginia Gazette, June 30, 1774.

[6] Ibid.