What connected people in early America? For some, it was blood ties. This was certainly true of Colonel Job Almy, an enslaver who belonged to one of Rhode Island’s oldest families. Arriving from England in 1630, the Almy family subsequently spread throughout the Narragansett Bay, with its patriarchs establishing themselves as yeomen, merchants, and local leaders. Colonel Almy’s grandfather Christopher Almy and his brother Job (one of the many men named Job in the Almy family) purchased land from the Indigenous Wampanoag in what became Tiverton, Rhode Island. And so the Almy family passed down the land to their ensuing generations, further solidifying their social ties.

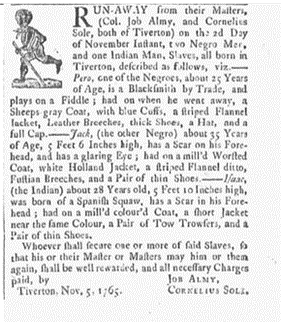

But what connected Pero, Jack, and Isaac, three Rhode Island runaways who Colonel Job Almy and his associate Cornellius Sole desperately wanted returned? Two commonalities emerge from Sole and Almy’s advertisement: all three men had apparently been born in Tiverton and all three were also enslaved. Perhaps this shared condition was enough to encourage a relationship among Pero, Jack, and Isaac. Like many enslaved people separated by their bondage, they may even have considered themselves related to one another. Indeed, Tiverton had been a young, unincorporated settlement when these three freedom seekers were born—meaning they likely grew up around each other. News of their daring actions surely resonated within the small community.

Despite their shared status and hometown, however, Pero, Jack, and Isaac led distinctive lives. We know very little about Jack and Isaac beyond their physical descriptions. Both had noticeable scars on their foreheads. Jack’s glaring eye could suggest that he had trouble seeing in the dark and perhaps needed accompaniment when traveling at night. The glare in Jack’s eye might also be read as a warning from his enslavers of what they perceived as menacing qualities, something which made enslavers uneasy.[1] Of the three, only Pero was described as a “skilled” laborer, having learned the trade of a blacksmith. As a blacksmith, Pero’s skills would have been in high demand both domestically in the farming community and aboard the many ships that flowed in and out of Narragansetts Bay. In addition to his facility at a forge, Pero could play the violin, a valuable skill that surely made him popular at many gatherings, perhaps among both Black and White people. Enslaved fiddle players were relatively common in New England, no doubt a reflection of the importance of music to the social and emotional lives of Black New Englanders.[2] Might Pero’s playing on a fiddle have accompanied enjoyable time spent together with Jack and Isaac?

Even though these men all came from the same small town in Rhode Island, their lives reflect connections forged within a much bigger Atlantic world. Both Pero and Isaac reflect aspects of the influence the Spanish had on New England. The name Pero is probably of Spanish origin and the nature of inter-colonial slave trading meant that some Africans with Spanish backgrounds ended up in places like New England.[3] We can only imagine the journey Pero’s mother must have made to Rhode Island, perhaps from Cuba or another Spanish Caribbean possession. Pero’s mother would have even continued to encounter Spanish speakers, primarily among a growing number of “Spanish Indians” like Isaac’s mother, who was described as a “Spanish Squaw.” Isaac’s mother was possibly an Indigenous woman sold into slavery from the southern colonies in the area around the Carolinas and Spanish borderlands.[4] Rhode Island held a unique place within the ever-changing imperial networks of the eighteenth century, welcoming ships and trade from all across the Americas and West Africa, a useful reminder of the often-forgotten diversity that characterized the colony. Whatever Pero, Jack, and Isaac thought of one another was undoubtedly influenced by this world, even if their actual personal opinions remain unknown.

Of course, the chance to attain freedom was one of the most powerful reasons these men would come together. Whether alone or in a group, the decision to seize freedom was a complex one, with many variables to consider. While the cooperation of other freedom seekers could increase their combined knowledge, skills, and courage, it also likely increased the chances of being caught. The anxiety and fear stoked by running away no doubt tested whatever bonds Pero, Jack, and Isaac created during their years of knowing one another. Unlike on plantations in the Caribbean or southern mainland colonies like South Carolina, Black New Englanders were a tiny proportion of the population. Blending in and hiding among other New Englanders posed a unique challenge. In contrast to men who paid for the newspaper advertisement, Pero, Jack, and Isaac probably had many fewer if any kin in the area.

This is not to say Pero, Jack, and Isaac lacked allies in their bids for freedom. Perhaps the three sought their freedom among Rhode Island’s Indigenous population. Isaac’s Native American heritage suggests the possibility of reconnecting with family. Pero’s skills as a blacksmith would have been highly valued by Narragansetts who could use his skills to repair guns, tools, and other implements. After the devastation of King Philp’s War almost a century earlier, various Narragansett peoples regrouped in and around Mount Hope Bay. Over the first half of the eighteenth century, they transformed Rhode Island’s countryside as they struggled to coexist alongside growing populations of White and Black New Englanders. Indeed, Pero, Jack, and Isaac’s escape coincided with growing alarm among Rhode Island colonists over interracial liaisons between Black men and Indian women and a growing population of mixed-race children, called “mustees” by colonists.[5]

Of course, Pero, Jack, and Isaac may have escaped independently or parted ways after running as a group. If not for this advertisement, we would know little of the bonds that existed among these men. Ironically, the evidence of the relationship between their enslavers has also disappeared from the historical record apart from this advertisement. Sole and Almy’s association persists in print, an allusion to the web of social ties among Whites that collectively supported bondage in New England. Whether Pero, Jack, and Isaac continued on separately or together, they were linked not only by the advertisement, but, more importantly, by their shared ambitions for freedom.

View References

[1] Samuel Johnson. A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from Their Originals and Illustrated in Their Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writer; to Which Are Prefixed a History of the Language and an English Grammar. 2nd ed. (London: Printed by W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755).

[2] William D. Piersen, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988) 103-104.

[3] Gregory E. O’Malley, Final Passages: The Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America, 1619-1807 (Chapel Hill: Omohundro Institute and University of North Carolina Press, 2016) 201-204.

[4] Margaret Ellen Newell, Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2015) 207-209.

[5] John Wood Sweet, Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, 1730-1830 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003) 172-174.