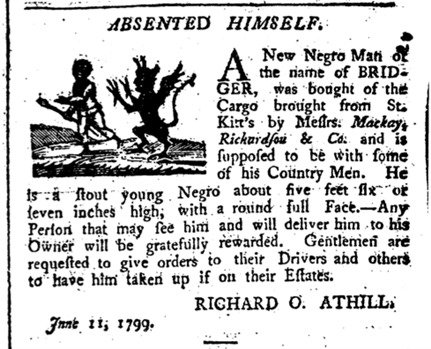

Two days after the above advertisement appeared in the Antigua Journal a second appeared in the Antigua Gazette, also published in St. John’s. The text of the two notices is virtually identical but the accompanying woodcut images are strikingly unusual. In each advertisement the crudely fashioned image of a freedom seeker on the run is accompanied by a devil.[1]

What do these images mean? There does not appear to be anything particularly distinctive about Bridger. The advertisements identify him as African, and recently purchased by Athill from Mackay, Richardson and Company. Athill believed that the freedom seeker might have sought refuge “with some of his Country Men,” meaning people from the same part of Africa who had endured the Middle Passage together. Bridger may well have arrived on board either the Mary, a Liverpool ship which had brought 181 enslaved people from West Central Africa, or the Harlequin, another English ship which brought 274 enslaved people from the same African region. Mackay and Richardson had advertised and then sold “Forty-Three Prime SLAVES” from Angola in November of 1798, quite possibly including Bridger.[2]

What might these devils have signified? In European literature and theater devils were commonly identified by their black faces, and in folk tales the devil was often referred to by such titles as “Black Knight,” “Black Jehovah” and “Black Man.” For centuries sub-Saharan Africans had often been visually identified by European artists on paper, stained glass, tapestries, and other media in ways that associated them with the devil or even as devils themselves. White men and women seeing these Antiguan advertisements might well have drawn on a symbolic lexicon that associated darkness with diabolical evil.[3]

Although the Enlightenment had weakened Europeans’ belief in the devil as an agent in human affairs, diabolical iconography did not quickly disappear from popular culture and folklore. The Prodigal Daughter, for example, was a mid-eighteenth-century work intended for children that told the story of a spoiled girl in Bristol who made a bargain with the devil. This story almost always included wood cut prints of a devil exercising a malign influence over the young woman. The Prodigal Daughter was reprinted regularly over the course of the eighteenth century, and this and similar publications kept alive the idea that the devil might be an active agent in human affairs.[4]

British enslavers in the Caribbean were terrified of the enslaved Africans who outnumbered them and who had every reason to wish evil to be visited upon their oppressors. In 1750 approximately 3,261 enslaved people lived on Antigua’s roughly one hundred square miles, but over the next fifty years almost 76,000 enslaved Africans were forcibly brought to the island: this was a society in which enslaved Africans massively outnumbered Europeans.[5] Antigua’s abortive slave rebellion of 1736 had featured obeah men as active participants. Drawing on ideas associated with the African diaspora, they administered oaths to would-be rebels and performed rites to assure the success of the rising. Whites were convinced that obeah had played a significant role in the rebellion. Whites responded by breaking five rebels on the wheel, gibbeting six of them while alive, and slowly burning seventy-seven alive, some of the most brutal punishments imaginable.[6]

Although Athill did not describe Bridger as an obeah man, White Antiguans might have readily identified him and other new arrivals with the beliefs and practices of Africa. White people in the Caribbean regarded real or “pretended” communication with the devil by enslaved West Africans as intimately connected to violent resistance ranging from poisoning of individual Whites to engaging in a revolution of the type underway in Haiti at the time of this advertisement. With this one simple and instantly recognizable image the runaway advertisement communicated the deadly dangers inherent in the rebellious escape of enslaved people. Moreover, by matching the blackness of the devil with the dark skin of the African freedom seeker, these advertisements enhanced this sense of danger, building on the long-standing European association of light with good and darkness with evil. It was all too convenient for Europeans seeking to justify their brutal enslavement of Africans to see the skin color of the enslaved as physical evidence of savage and dangerous natures.[7]

Was the devil an accomplice or an instigator of the rebellious escape of enslaved people? In both advertisements for Bridger the devil appeared behind the freedom seeker, his arms and clawed hands raised in threat while the escaping freedom seeker looked anxiously over his shoulder at the chasing devil. The testimony of rebels in the Antiguan slave conspiracy earlier in the century had made clear that many of the enslaved were terrified of the spirit world, and of obeah men and women who were believed to exercise some of its power. Were these images intended to suggest that obeah men terrified the enslaved into resistance, including escape?

Whether consciously or not, White European readers interpreted these descriptions in ways that were informed by centuries of associating blackness both with Africans and with evil. However unusual these Antiguan images were, they nonetheless signified a range of European interpretations of enslaved Africans that drew on a European symbolic lexicon that was all but universal. The image of two black figures, with a devil running behind a freedom seeker, communicated the dangers inherent in what Whites interpreted as the uncivilized, savage, and pagan beliefs and practices of enslaved Africans who dared to challenge their subordinate position.

View References

[1] The advertisement in the Antigua Journal was reprinted June 18, while the one in the Antigua Gazette was reprinted June 20 and June 27. Similar advertisements featuring freedom seekers and devils were published in the Antigua Journal on November 6, 13, 20 and 27, 1798 (for Quashey), and July 23 and August 6 (for Farley). The American Antiquarian Society (Worcester, Massachusetts) holds most issues of the Antigua Gazette and the Antigua Journal published between July 1798 and October 1799. It is possible that woodcuts of devils and runaways were similarly juxtaposed in issues of the newspapers that have not survived.

[2] It has not been possible to determine which ship brought Bridger from Africa to the Caribbean. Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database reveals that nine ships brought enslaved Africans to St. Kitts between 1795 and 1799, almost all of them from West Central Africa (seven of the nine ships). Only the Mary and the Harlequin appear to have arrived at the right time, in 1798, and if the information in the runaway advertisement is correct, one of these ships sold part of its human cargo in St. Kitts and then sold some or all of the remainder in Antigua. Only the Young Ralph, another Liverpool ship, arrived in Antigua between 1797 and 1800. This ship brought 230 enslaved people to Antigua in 1797, but if Bridger had been on this ship it is less likely that the advertisement would have referred to him as “A New Negro Man” given that he would have been on the island for at least two years, and the advertisement probably would not have referred to the merchants who sold him. See http://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/search?submit_val=restore_prev_query&prev_query_num=0 (accessed 21 May 2017). “NEW NEGROES TO be Sold at the Store of MACKAY RICHARDSON & Co,” Antigua Gazette, Thursday 2 May 1799, 3.

[3] Debra Higgs Strickland, Saracens, Demons, & Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 61-74, 83-86. See also Joseph Leo Koerner, “The Epiphany of the Black Magus Circa 1500,” in David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. eds., The Image of the Black in Western Art, Volume III: From the “Age of Discovery” to the Age of Abolition, Part 1: Artists of the Renaissance and Baroque (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2010), 71-81; Jean Devisse and Michel Mollat, “The Appeal to the Ethiopian,” in David Bindman and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. eds., The Image of the Black in Western Art, Volume II: From the Early Christian Era to the “Age of Discovery” (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2010), 83-152.

[4] The Prodigal daughter: or A strange and wonderful relation, shewing, how a gentleman of a vast estate in Bristol, had a proud and disobedient daughter, who because her parents would not support her in all her extravagance, bargained with the Devil to poison them… Likewise the substance of a sermon preached on this occasion by the Reverend Mr. Williams, from Luke 15:24. (Boston: Thomas Fleet, between 1742 and 1754).

[5] Vere Langford Oliver, History of the Island of Antigua… (London, Mitchell and Hughes, 1894), I: cxv. The ‘Estimates’ function of the transatlantic slave trade database indicates that between 1751 and 1800 perhaps 75,998 Africans were brought to the island. See Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database http://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates (accessed February 15, 2024).

[6] David Barry Gaspar, “The Antigua Slave Conspiracy of 1736: A Case Study of the Origins of Collective Resistance,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 3d. ser., 35, 2 (1978), 308-323; David Barry Gaspar, Bondsmen and Rebels: A Study of Master-Slave Relations in Antigua (Durham: Duke University Press, 1985), 3-37; Diana Paton, The Cultural Politics of Obeah: Religion, Colonialism and Modernity in the Caribbean World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 35-6.

[7] There is a growing literature on the developments of ideas of race and blackness. See, for example, Craig Koslofsky, “Knowing Skin in Early Modern Europe, c. 1450–1750,” History Compass 12 (2014), 794–806; Roxann Wheeler, The Complexion of Race: Categories of Difference in Eighteenth-Century British Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000); Colin Kidd, The Forging of Races: Race and Scripture in the Protestant Atlantic World, 1600–2000 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Andrew S. Curran, The Anatomy of Blackness: Science & Slavery in an Age of Enlightenment (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011); Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, ed. Race and the Enlightenment: A Reader (New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008).