On November 18, 1771, two of Nathaniel Burwell’s enslaved people absconded from his place in Warrasqueak Bay. Unlike most planters of his day, he elected to wait before turning to print. Rather than solicit the attention of his neighbors by way of a newspaper advertisement, the Virginia grandee might have thought a more sensible course of action would be to give the couple time to return home on their own.[1] In that regard, the owner of the Carter’s Grove plantation in James City County might have had another reason in mind for giving these people time alone. During their time together, he might have thought, the couple’s union could prove fruitful, producing an offspring, enlarging ultimately his already large estate. Slave breeding, after all, had been a common part of the peculiar business of slavery in the Chesapeake.[2]

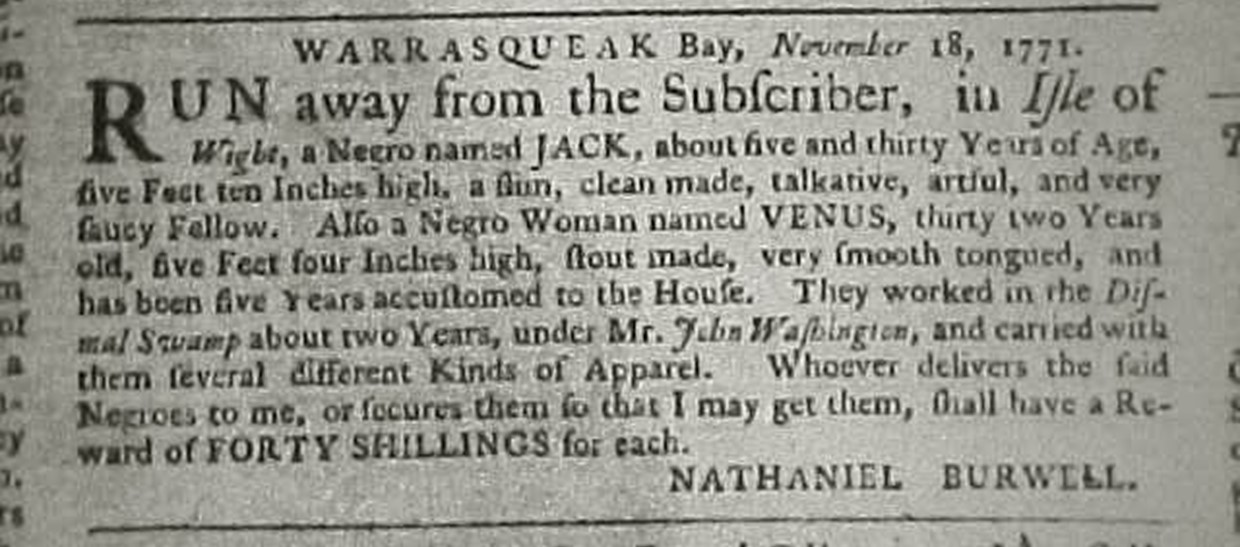

His magnanimity, however, had its limits. After a month had passed and having received no news as to the whereabouts of his unruly property, Burwell sent his agent to Williamsburg and had an advertisement printed in the Virginia Gazette. In mid November, the notice revealed, two of the enslaved people held by Nathaniel Burwell had absconded. He described the first fugitive, a “Negro named Jack” as “a slim, clean made, talkative, artful, and very saucy Fellow.” The other, a “Woman named Venus,” he described as “stout made, very smooth tongued, and has been five Years accustomed to the House.” Both were thirty years old when they decided to steal themselves. Both carried away additional articles of clothing. Burwell suspected that they not only had run away together, but also were probably headed toward the Great Dismal Swamp. For two years before, the notice and another extant record explained, both worked under John Washington, George Washington’s brother and the overseer of the Dismal Town plantation that had been a sanctuary of sorts for a few African Americans and for a variety of reasons.[3]

With the North star at their backs, the couple made their way back to the Dismal Swamp. Clearly, they thought the place was different from the one they left behind. Although forced to work as part of the Dismal Swamp Company, a joint business venture that attempted to harvest the natural resources of the 2,000-square mile area on the border between Virginia and North Carolina, they might have discovered one another there. With its thick foliage of cypress, maple, and pine trees, the swamp provided Jack and Venus an opportunity to fall in love. That is to say, when not clearing parts of the land, or making shingles, or cultivating rice and corn, the two enslaved African Americans found time to talk, court, and entertain the possibility of marriage.

What is more, the new couple might have found time to realize a sense of community. In the absence of their enslaver, whose place had been some thirty miles away, Jack and Venus likely socialized with other enslaved African Americans who were hired out to the Dismal Swamp Company. Despite the rough terrain, they were forced to navigate, the couple might have realized some degree of freedom. They might have achieved a sense of economy. They might have also even engaged members of the various maroon communities that peppered the landscape of the swamp. Their time in the wetlands, however, did not last long. At end of Burwell’s contract, they were returned.[4]

Since neither Jack nor Venus agreed to any of the terms of Burwell’s contract with the Dismal Swamp Company, the couple took matters into their own hands and elected to steal away. Interestingly, they decided to return to that place where they might have found love and one another. Several advertisements printed in the Virginia Gazettes reveal those details. After the first advertisement he had published in the newspaper, Burwell had it reprinted on January 30, 1772. This reprint suggests that the couple had not been taken up for at least one month. By March, however, it appears that they ran away again. Like before, they ran away together. On April 2, they resumed their joint flight. In the month of May, Burwell advertised the couple as missing on three separate occasions. Almost a full year would pass before either Jack or Venus’s name would reemerge in the newspapers. On February 18, 1773, Robert Burwell placed a notice in Rind’s Virginia Gazette for a fugitive, “Negro Man named Jack Dismal.” The description of the freedom seekers almost matches the one Nathaniel Burwell had printed in the paper before in its description of Jack. The new detail, that is the man’s surname, Dismal, might reflect Jack’s time working for the Dismal Swamp Company. Five years later, on July 10, 1778, Jack Dismal ran away again. On that occasion, however, yet another Burwell, Mary, had a notice printed in the Gazette. Jack, she reported, did not leave alone. Instead, the man absconded with his wife, “Venus,” and two other women, “Zeny” and her daughter “Nelly.” Clearly, for the enslaved couple the Dismal Swamp proved not only a special place, but also their refuge, both real and symbolic.[5]

View References

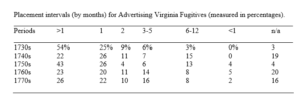

[1] Most enslavers in Virginia advertised between one and three weeks after enslaved people absconded. Burwell prove the exception to that general rule.

Sources: Lathan A. Windley, Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History. New York: Greenwood Press, 1983. 4vols; Billy G. Smith and Richard Wojtowicz, Blacks Who Stole Themselves: Advertisement for Runaways in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728–1790. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989; Graham Russell Hodges and Alan Edward Brown, ‘Pretends to Be Free’: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial and Revolutionary New York and New Jersey. New York: Fordham University, 1994; Antonio T. Bly, Escaping Bondage: A Documentary History of Runaway Slaves in Eighteenth-Century New England, 1700–1789. Maryland: Lexington Books, 2012; Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers Database; and, Eighteenth-Century American Newspapers in the Library of Congress in Microfilm.

For a useful biography of Burwell, see https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/burwell-nathaniel-1750-1814/.

[2] For a fuller account of the Dismal Swamp Company, see Marcus P. Nevius’s City of Refuge: Slavery and Petit Marronage in the Great Dismal Swamp, 1763-1856.

[3] Venus and Jack’s name appears on John Washington’s 1764 company list. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-07-02-0191 For a useful history of the Dismal Town, see Marcus P. Nevius’s City of Refuge.

[4] In addition to Marcus P. Nevius’s City of Refuge: Slavery and Petit Marronage in the Great Dismal Swamp, 1763-1856, Sylviane A. Diouf’s Slavery’s Exile: The Story of the American Maroons for fuller account maroons in the Dismal Swamp.

[5] Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), January 30, 1772, 4; Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), March 19, 1772, 4; Virginia Gazette (Rind), April 2, 1772, 4; Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), May 7, 1772, 4; Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), May 14, 1772, 4; Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), May 28, 1772, 4; Virginia Gazette (Rind), February 18, 1773, 3; Virginia Gazette (Purdie), July 10, 1778, 3.