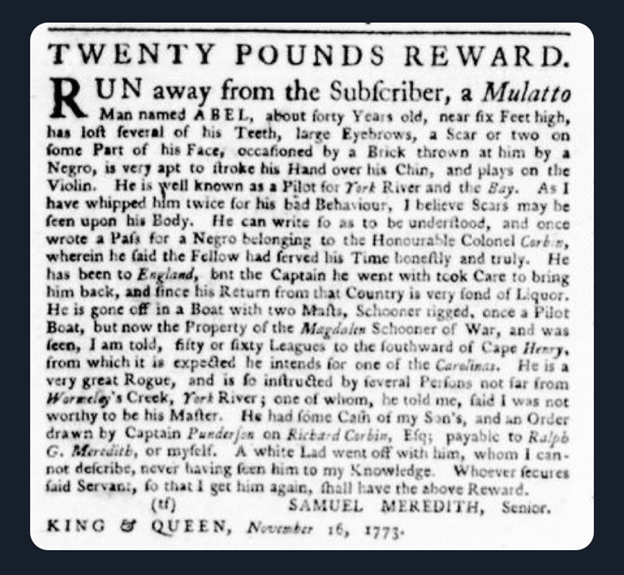

Abel was born about 1730. Identified as a “Mulatto,” he was almost certainly the son of a white man and an African-born or African-descended woman. If he was born in Virginia, his mother could have been one of the many girls and women enslaved and transported to the Americas in the early eighteenth century. Perhaps Abel was conceived in an act of rape or of coerced sex, as sexual abuse was endemic within the slave system. It is possible as well that his name was chosen by the very man who forced himself upon his mother. But perhaps not. It might be that Abel’s mother named him or that he selected his name for himself. In both Christian and Islamic traditions, Abel was known as the younger son betrayed by his older brother, Cain, and subjected to extraordinary violence that resulted in death. Perhaps this story resonated with the man who took his freedom into his own hands in Virginia in 1773. Violence certainly marked his life. A strapping man of nearly six feet, Abel had suffered confrontations with at least one other Black man, as well as with his enslaver, who had whipped him at least twice. He bore the scars to prove it.

Powerful and bold, Abel was also a man of skill and learning. His enslaver discussed his habit of stroking his chin, a sign of thoughtfulness. He could bow the violin, a skill developed by many enslaved men. He could also read and write. By 1773, the year he escaped enslavement, Abel had already used his skill in composition to write a pass for another enslaved man, not only to secure the man passage but also to state that he “had served his Time honestly and truly.” This was an ingenious document, far beyond the standard of a typical pass. It sought not only to give its bearer freedom of movement, as was the norm in passes, but also to attribute to him the most sterling and steadfast qualities of workingmen. And Abel’s literacy extended to the cartographic ability to read maps—possibly even to create them—which would have helped him as a navigator. Maps were a genre of their own; those depicting rivers and coastal zones included soundings, place names, and information about wind and currents.

In 1773, Abel used his skill in navigation to seek his own freedom. In this quest, the land, the waters, and watercraft were all crucial elements. Abel was adept as a “Pilot for York River and the Bay,” that is, Chesapeake Bay. King and Queen County, today east of Richmond, had an extensive bank along its southern tip on the York River, providing a natural outlet to the Chesapeake Bay: a route for Abel to train as a pilot and, in 1773, to seek freedom. Tobacco and other goods flowed east from Richmond for the Atlantic trade, so Abel would have been well familiar with routes of travel and ways that profits were made. In a remarkably bold move, he seized a two-masted schooner that probably served as a pilot boat for a schooner of war, the Magdalen. A six-gun craft with a complement of sixty men, the Magdalen sailed in 1769 from Portsmouth Dockyard, where she was fitted, to service in the Royal Navy in the British North American colonies; she was decommissioned in 1777.[1] Even a skilled pilot would need a second hand on board to sail the pilot boat, particularly if his goal was to the south, “the Carolinas,” where offshore waters were treacherous. It makes sense that Abel had a shipmate: A “white Lad went off with him,” Abel’s enslaver claimed. In a vessel with this profile, two masts and at least three sails, speed would have been essential to avoid detection. The boat had already been spotted “fifty or sixty Leagues to the southward of Cape Henry,” which meant about 190 land miles south of the opening of Chesapeake Bay. A rough approximation is the mid-point between Cape Hatteras (to the north) and Cape Fear (to the south).

The advertisement suggests that a guiding experience in Abel’s life was a trip to Great Britain, which exposed him to open ocean navigation and, quite possibly, to the 1772 Somerset vs Stuart case, which asserted the right of enslaved people to freedom in England. Abel “has been to England,” the advertisement states, “but the Captain he went with took Care to bring him back.” If Abel’s trip took place after the Somerset decision, no one could legally have forced him to sail back to Virginia—and to slavery—alongside the captain. Yet return to Virginia Abel did (though likely not of his own free will). Nonetheless, the Somerset case may have had an effect on Abel. Perhaps the man became determined gain his freedom upon hearing of it. He may also have come to believe that if he eventually stepped into a free territory he would then be unenslavable.[2]

When Abel absconded in 1773, he took cash with him, suggesting skill in counting. He also took an “Order,” which was a voucher payable on demand, suggesting familiarity with financial instruments. That the order was payable to his enslaver and that Abel apparently intended to convert it to cash surely infuriated the man. The description of Abel as “a very great Rogue” was part of a pattern in advertisements whereby Black people were tarnished as disruptive and prideful. Indeed, his enslaver suspected that, in Abel’s eyes, “I was not worthy to be his Master.” Abel’s enslaver blamed the man’s trip to England for a fondness of liquor despite the fact that strong spirits were a common feature of both Black and white life in Virginia. Less than thirty years later, in 1800 in Richmond, alcohol consumption among the insurrectionists of Gabriel’s Rebellion would be closely scrutinized by the court that tried the men after the uprising faltered.[3] The implication in 1773, as in 1800, was that Black men who drank were a problem, but in reality alcohol permeated the lives of men of all races.

Nothing seems to be known about Abel after his bid for freedom. However, his enslaver, Samuel Meredith, Sr., left additional records that allow more insight into Abel’s life. In 1767, Meredith advertised a reward of 20 shillings for information concerning thieves who had stolen a mare belonging to his son.[4] He stated that the mare had been taken at his plantation near Dudley’s Ferry and he requested that information be delivered to him at West Point, Virginia. Dudley’s Ferry was on the banks of the York River; it carried passengers to and from West Point, about 30 land miles to the northwest, directly east of Richmond and at the fork where the Mattaponi and Pamunkey Rivers join to form the York River.[5] It seems likely that Abel was familiar with both Meredith’s home at West Point and his plantation near Dudley’s Ferry. It might have made more sense for him to embark on his freedom journey near the plantation, rather than from West Point, where he might have been missed sooner. When he seized the pilot boat, moreover, he would have preferred to be as close as possible to open water, not in a river with, possibly, close traffic and prying eyes nearby. Yet we cannot know for certain where he commenced his journey to freedom. That Abel escaped in the fall of 1773 and Meredith advertised a reward in December 1773 and again in January 1774 suggests that the white man knew there was no hope of an informal method of recapturing the Black man or of a voluntary return on Abel’s part. A hefty reward of twenty pounds offered within a few weeks of the escape suggests that Meredith had measured Abel’s monetary value and had no hope of an easy return.

View References

[1] For information on the Magdalen, see Rif Winfield, British Warships in the Age of Sail, 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates (Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK, 2007), 327.

[2] For one of the many fine and useful analyses of Somerset vs Stuart, see William R. Cotter, “The Somerset Case and the Abolition of Slavery in England,” History 79, no. 255 (1994): 31–56.

[3] John Saillant, “Covenants and Craftsmanship in Gabriel’s World: Hermeneutics and Material Culture in an 1800 Slave Rebellion,” The Journal of Black Religious Thought 1, no 2: (2022): 173–95, analyzes the trial testimony concerning the Black conspirators’ consumption of alcohol.

[4] “Strayed or stolen from my plantation,” Rind’s Virginia Gazette, 24 December 1767, p. 3, advertised Meredith’s offer of a reward of 20s for a stolen mare. Meredith was offering a reward for the mare within two weeks of its disappearance (recorded on 12 December 1767), whereas he waited more than two months (from 16 November 1773 to 27 January 1774) to do the same for Abel, implying that he initially believed that a less formal and more personal—and less costly—process might eventuate in Abel’s return. Since 20 shillings equaled one pound, Meredith’s offer of 20 pounds for Abel’s return was 20 times what he had offered for information on the horse.

[5] “This is to inform the public,” Rind’s Virginia Gazette, 29 March 1770, p. 4, advertised travel by water between Dudley’s Ferry and West Point, Virginia.