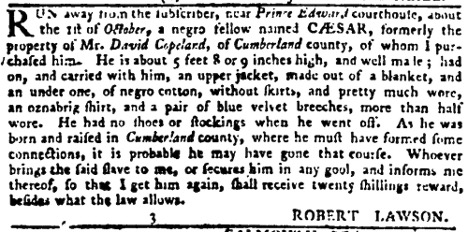

On or about October 1, 1774, an enslaved Virginian named Caesar slipped away from the site of his bondage, ascended and crossed the Appalachian Mountains, likely descended the Kanawha River to the Ohio, and made his way to the Shawnee villages on the lower Scioto River in the Ohio country, where he sought sanctuary.[1] Caesar was one of perhaps hundreds of slaves in Virginia and Maryland who made their way to Native American villages in the Ohio country during the era of the American Revolution. We know more about his biography than most thanks to the work of Shawnee genealogist Don Greene and a runaway advertisement posted in the Virginia Gazette by his owner. Born about 1740 in Cumberland County in the Virginia Piedmont, his parentage reflected the triracial heritage of colonial America. His father, an African, had been enslaved and transported across the Atlantic in the Middle Passage. His mother was a mestizo slave from Bermuda of mixed Spanish and Shawnee descent. The property of David Copeland of Cumberland County during his childhood and youth, Caesar was owned at the time of his escape by Robert Lawson of Prince Edward Court House, a man of some local importance. His mother’s partial Shawnee ancestry likely played a role in his decision to set out for the Ohio country.[2]

In late 1774, not long after reaching the Shawnee villages on the Scioto, Caesar was adopted into the tribe. At about the same time, he met and married Sally, a fourteen-year-old meti girl of mixed Shawnee and white racial heritage. Sally belonged to the Kishpoko division, the warrior clan within the Shawnees. Together, they produced several children over the next three decades. Two of these, named “Sally’s white son” and “Sally’s black son” because of their difference in skin color, left the greatest mark in the historical record, joining Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa (also known as the Prophet) by 1811 in their effort to construct a Pan-Indian confederacy at Prophetstown on the Wabash River in central Indiana.[3]

As part of the Kishpoko clan, Caesar fought with other warriors to try and hold on to the Ohio country. He took part in conflicts at Point Pleasant on the upper Ohio (1775-1778), at the siege of Boonesborough (1778) and the Battle of Blue Licks (1782) in Kentucky, and Crawford’s Defeat (1782) in the Sandusky River valley in northern Ohio. From 1788 through 1792, he was involved in other raids on white settlements throughout the Ohio River valley. Meanwhile, these conflicts dislodged his family and his adopted people. In 1777 many Shawnees, including Caesar and Sally, abandoned their homes on the Scioto and moved northwestward to the Great Miami, Little Miami, and Mad rivers, where they established new villages.[4]

We have few details of Caesar’s exploits as a warrior. There is a single exception. In the Fall of 1786, General Benjamin Logan led American troops and his sizeable Kentucky militia, some 780 men in all, on an expedition against the villages that constituted the Shawnees’ new home. The main attack was to be against the seven villages on the Mad River – where Caesar and Sally lived. Caesar, who was unaware of Logan’s purpose, signed on with the Americans as a scout and guide. As the American forces neared the Mad River villages Caesar learned of the Americans’ intent to make a surprise attack, and he slipped away into the night, warning the Shawnees of what lay in store. Many Shawnees quickly packed up their belongings and fled. Logan and his forces found some of the villages empty but in others they killed twelve Shawnees, captured seventy-five more, plundered their villages of anything of value, and set fire to their homes and cornfields.[5]

About a thousand Shawnees, including Caesar and Sally, then built new towns some one hundred miles to the north. From 1787 to 1792, they lived in the Shawnee village at Kekionga, the site of contemporary Fort Wayne, Indiana, and a major trading center at the confluence of the St. Joseph, St. Mary’s, and Maumee rivers. From 1792 to 1794, they lived in the Shawnee village at The Glaize, the site of contemporary Defiance, Ohio, and an old buffalo wallow at the confluence of the Maumee and Auglaize rivers. Both Kekionga and The Glaze were diverse communities of villages that included Shawnees, other Indigenous peoples, French traders, and even people of African descent.[6]

Caesar became attracted to the efforts of Shawnee leader Blue Jacket to construct a pan-Indian confederacy to resist further white encroachment. He likely fought in Native American victories known as Harmar’s Defeat (1790) and St. Clair’s Defeat (1791) in northwestern Ohio, which demoralized the American army and persuaded many Indians they could retain control of most of the Ohio country. Caesar may have been a warrior in the decisive and unfortunate Battle of Fallen Timbers (1794) on the Maumee, in which Native Americans were thoroughly routed and their villages and cornfields burned. In the Treaty of Greenville (1795) that resulted from the defeat, Native Americans were forced to sign away claims to the southern and eastern two-thirds of Ohio.[7]

After the decisive defeat at Fallen Timbers, many Shawnee warriors determined to stop fighting and migrate westward. Caesar was one of them. In 1812 he and Sally joined some 1200 Shawnees who left the Ohio country after 1790 for fertile farmland along Apple Creek just north of Cape Girardeau, Missouri. Many of these were Kishpoko. There they continued to speak their Indigenous language, hunt and farm, gather nuts and roots, process animal skins, and celebrate Shawnee rituals. Even so, their cabins resembled those of their white neighbors. The presence of so many white neighbors brought growing conflict, theft of their livestock, ransacking of their houses, and occasional violence against the Shawnees themselves. It must have been a troubling time for Caesar and Sally, who apparently died at Apple Creek during the decade that followed.[8]

Caesar is an early example from the Indian Country of the Old Northwest of what historian William Loren Katz has described as “Black Indians,” that is people of dual African and Native American ancestry or “black people who lived for some time with Native Americans.” Caesar embodied both parts of this definition. His life illustrates that enslaved people who escaped during the revolutionary era pursued a variety of strategies. They did not all join the British, and that some headed westward or in some cases southward and forged new lives with Indigenous communities.[9]

View References

[1]Virginia Gazette, November 10, 1774; Don Greene, Shawnee Heritage I: Shawnee Genealogy and Family History (Research Triangle Park, NC: Lulu Press, 2008), 57; Don Greene, Shawnee Heritage VI: 1700-1750 Surnames C-D-E (Research Triangle Park, NC: Lulu Press, 2014), 9.

[2]Virginia Gazette, November 10, 1774; Greene, Shawnee Heritage I, 57; Greene, Shawnee Heritage VI, 9.

[3]Greene, Shawnee Heritage I, 57, 268-69.

[4]Greene, Shawnee Heritage I, 57; Colin G. Calloway, The Shawnees and the War for America (New York: Penguin Books, 2007), 63.

[5]David Wagner, ed., Historic Glimpses of Logan County, Ohio (n.p.: Logan County Historical Society, 2003), 9; George F. Robinson, History of Greene County, Ohio (Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1902), 180, 226.

[6]Colin G. Calloway, The Victory with No Name: The Native American Defeat of the First American Army (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 29, 98; Helen Hornbeck Tanner, “The Glaze in 1792: A Composite Indian Community,” Ethnohistory, Vol. 25 (1) (Winter 1978), 15-19.

[7]Greene, Shawnee Heritage I, 57; Calloway, Victory with No Name, 64-153.

[8]Greene, Shawnee Heritage I, 57, 268; Stephen Warren, The Shawnees and Their Neighbors, 1795-1870 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 75-81.

[9]William Loren Katz, Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage (New York: Atheneum, 1986), 5.