The oppressive humidity and heat filled the house. The symphony of crickets and a continuous hum of mosquitoes perhaps woke many from their sleep. Within this dimly lit room, the only light source was the moon filtering through the lone glassless opening. Illumination from the moonlight revealed the faces of some of the ten enslaved African Americans, tightly packed within. These crowded quarters only added to the stifling environment of North Carolina’s summers in which they were compelled to rest. In the distance, the sounds of livestock—neighs and grunts—echoed from the nearby barn. A similar room, across the hall, housed another ten enslaved African Americans; downstairs mirrored this setting with two more identically crowded quarters. Horton Grove slave quarters were on Stagville Plantation, which at its peak would confine a staggering 900 enslaved individuals.[1]

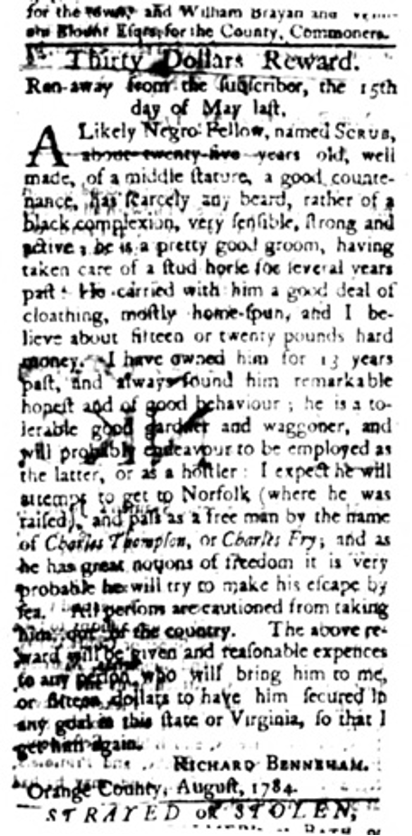

Charles Thompson was courageous enough to attempt to escape from this plantation and gain his freedom. He had been enslaved at Stagville since 1771 and was referred to by his enslaver Richard Bennehan as “Scrub.” Thompson’s escape in 1784 was recorded in an advertisement Bennehan placed in the North Carolina Gazette, in which he acknowledged that the freedom seeker had rejected this derogatory name. The advertisement suggests Thompson, the name the freedom seeker had chosen for himself, may have headed north to Norfolk, Virginia where he had been raised. Thompson was 25 years old at the time of his escape, meaning he was about 12 years old when he was purchased by Bennehan, and possibly separated from his family.

Thompson was entrusted by Bennehan with a significant responsibility. The young man had the duty of caring for a valuable stud horse, no doubt one of Bennehan’s most prized possessions. Thompson’s skills as a groom were particularly important to Southern gentlemen, for these enslavers were extremely enthusiastic about horse racing. Jockey clubs and racetracks existed across the Upper South and annual races evolved into significant social gatherings.[2] As horse breeding became a thriving business, wealthy landowners like Bennehan became “turfmen” who sought to enhance their status by investing in and training horses.[3] However, it was the skill and labor of Black men that made this sport what it was.

As a groom Thompson likely enjoyed certain privileges and what could have appeared to enslaved field workers as an easier life.[4] Grooms had some control over the conditions of their work, and their knowledge and expertise meant that White turfmen like Bennehan valued their opinions. Another indication of Thompson’s relative privilege was the money he took with him on his escape. According to Bennehan, he had taken with him about fifteen or twenty pounds in coins that Thomspon had earned. Bennehan’s language suggests his surprise that Thompson would give up these privileges: “I always found him remarkably honest and of good behavior; he is a tolerably good gardener and waggoner.”

But Charles Thompson’s notions of freedom did not begin with his escape, for he already had asserted his individuality by rejecting the derogatory appellation “Scrub” and choosing for himself the full and proper names “Charles Thompson” or “Charles Fry.” Still, the choice to leave Stagville could have been difficult for Thompson, risking his safety and leaving behind his home of twelve years. Perhaps Thompson’s position and sense of his own status might have isolated him from others within the enslaved community. As a groom he was likely forced to interact more with White people than many enslaved field workers, perhaps even causing tension in Thompson’s relations with other enslaved people at Stagville. Social isolation would surely worsen the long separation from his family and amplify his desire to reunite with them. But this time Thompson was making the break himself.

We don’t know how Thompson escaped. Bennehan assumed that Norfolk was his final destination, a journey of nearly 200 miles. Bennhan was so confident he knew Thompson’s plan, he not only placed an advertisement in the North Carolina Gazette but also invested money in the publication of an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette. If Thompson did indeed embark on this lengthy journey back to Virginia, his skills and local knowledge gained through occasional work for Bennehan as a waggoner surely made his escape a little easier. The 1790 North Carolina census shows 2,000 enslaved individuals among a population of 12,000 in Orange County, where Stagville was located.[5] A few of these enslaved people were waggoners who delivered goods for their enslavers. Thompson’s time on the roads may have given him knowledge of different routes, and where he might expect to encounter White men on the roads. He possibly made friends with fellow African American waggoners who could have aided him in his escape. This type of knowledge, connections with other waggoners, experience, and his skill with horses could all have been factors in Thompson’s escape.

Thompson would have traveled through a mixture of cultivated farmland and densely wooded areas. We might imagine him hidden in a wagon, or walking along the roads watching carefully for any sign that White men were approaching. He would have listened to the rhythm of horse hooves on the road and the sound of the springtime breeze in the trees. Beams of light that filtered through the abundant forest canopy could have gently warmed his skin. Every time he caught sight of an unfamiliar wagon on the road his heartbeat must surely have quickened. The sheer panic that may have overcome him had to be suppressed if he was to pass without suspicion. As unspecified figures approached, Thompson may have concealed himself in the woods, or given a cautious, yet subtle, glance to ensure his identity and intentions remained concealed. Only after the people he encountered had passed would Thompson have breathed a sigh of relief and continued with his journey. Escaping was dangerous and terrifying, and even if we know Thompson’s likely destination, we can hardly begin to imagine how it felt to take his life and future in his hands, and risk everything to be free.

View References

[1] Jean Bradley Anderson, Piedmont Plantation: The Bennehan-Cameron Family and Lands in North Carolina. Durham: Historic Preservation Society, 1985.

[2] Katherine Mooney, Race Horse Men: How Slavery and Freedom Were Made at the Racetrack (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014) 23.

[3] Mooney, Race Horse Men, 5.

[4] Mooney, Race Horse Men, 9.

[5] North Carolina – From Early Statehood to 1800 1790 NC Census Summary by County.” North Carolina – 1790 Census Summary, www.carolana.com/NC/Early_Statehood/nc_1790_census_summary.html. Accessed 11 Nov. 2023.