Around Christmas of 1810, a young boy, an adolescent of 14 or 15 years of age, whose name we will never know, is “picked up” in Fort Royal, Martinique, on the road leading to Fort Bourbon. He is found “in a dying condition.” The boy neither protested about being free, nor was he able to present freedom papers to prove so. He had simply decided at some point in his short life that it was enough. The advertisement’s wording hints at the violence and terror he must have endured since even in this state or rather because of it, he refuses to say his name or that of his enslaver. If he was African-born, he would have known his birth name, as well as the one that his enslavers might have imposed on him, but intentionally chose to stay silent. Living in a regime that sought to strip him of his humanity and self-determination, this was a deliberate act of resistance. It might even be his last one considering that he appeared to be dying.

From the advertisement, it is not obvious if he was born in the West Indies or if he was trafficked into the Caribbean around 1795 from Africa. The advertisement comments that he speaks English and French remarkably well, the underlying assumption being that many other notices for freedom seekers made clear that they spoke broken English or even could not speak it. He might have been brought into the Caribbean as a very young child, considering that he had learned both languages well. Perhaps he had learned English and French growing up in Martinique, or he had learned the languages in other colonies before being trafficked to the island. For at least part of his life Martinique had been under British control.[1]

If he had indeed escaped, the timing—some weeks before Christmas—may have been meaningful. He might have learned that his enslaver planned to sell him away in the New Year. The prospect of being torn, perhaps not for the first time, from a place that even if violent would have been the place that he might call home, and where he might be together with his mother or other family members and friends, would surely have been terrifying. Or if he was indeed African-born, he might have been trafficked to the Caribbean alone. Without a support network of family and friends to aid him in his escape, without food and water, and facing the heat of the island, he may have grown weaker and weaker. Although there were maroon communities in the interior, mountainous part of Martinique, the young boy did not have the stamina to navigate there. Alternatively, he might have escaped after suffering violence at the hands of his enslaver or others. Perhaps he had summoned up the courage to file a complaint with the royal magistrate about physical abuse and mistreatment, before he was found in a pitiable state on the road to Fort Royal.[2]

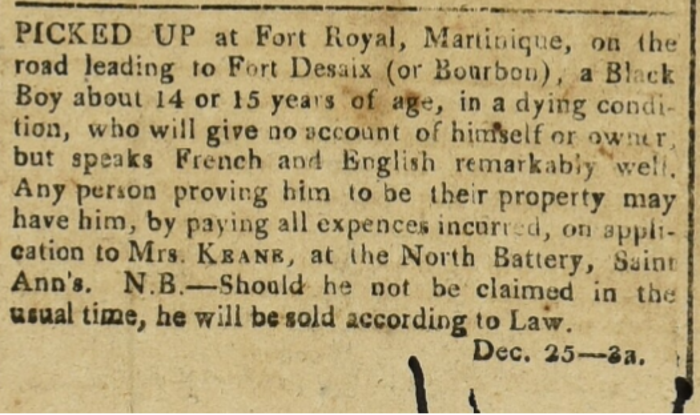

We learn about this boy from an advertisement placed in the Barbados Mercury, and Bridgetown Gazette on 29 December 1810.[3] Nested among other advertisements for sales of goods and plantations on the first page of the Barbados Mercury, this short notice (like others for freedom seekers), was a tool of persecution. The boy was considered chattel property and the newspaper made known his whereabouts so that anyone who could prove he was their “property” would be able to reclaim him, “paying all expences (sic) incurred,” otherwise he would be sold. To reclaim him, people should address Mrs. Keane “at the North Battery, Saint Ann’s.” Since it was illegal to take enslaved people from an island to the other, and to avoid prosecution, Ms. Keane was eager to emphasize that she was doing everything “according to Law.”

Ms. Keane might have been Elizabeth Keane, a “free Mustee woman” from Barbados.[4] Elizabeth had lived openly with Michael Keane, a well-connected plantation lawyer who emigrated to the Caribbean from Ireland.[5] Keane operated first out of Barbados, where he must have met Elizabeth, and later moved to St. Vincent together with her, rising to become the attorney general there. Michael Keane became a major figure in the colonization of the Caribbean, and after acquiring two plantations and considerable property in St. Vincent, “the Keane family would become so successful that they merged first into the West Indian planter society and, after achieving their fortune, the English gentry.”[6] As a Catholic Irish lawyer, Michael Keane would have been a somewhat liminal yet influential person, connecting through his contacts and alliances not only with planters and regional merchants in the British Atlantic, but also through Catholic networks with clients in various cities in Ireland, in ceded islands, such as Dominica and Grenada, and in French colonies like Martinique and Guadeloupe.[7]

The advertisement does not specify why and how Ms. Keane came to have the boy in her possession. After Michael Keane’s death in 1797, he had left Elizabeth fifty pounds “in consideration of her faithful services,” and directed that she be permitted to stay in her chamber at his Liberty Lodge plantation “until she thinks proper to return to Barbados or go elsewhere without any molestation by my son or any other person.”[8] It seems indeed that Elizabeth returned to Barbados where to survive she might have opened a tavern at St. Ann’s garrison or a boarding house, as many free women of color did.[9] Considering that Martinique was under British occupation at that time, maybe one of the Royal Navy officers found the boy and brought him back to the garrison. Or Ms. Keane might have been traveling in Martinique at that time, found the boy, and brought him to the island with her. Elizabeth would have nurtured the boy back to health, and then, after his sale, she would recoup her expenses, or she might even seek to buy him herself. In any case, she provided no specific physical characteristics about the boy other than his age and the place he was found. Maybe Mrs. Keane wanted to reveal enough information to ensure she would not be prosecuted, but not as much as to make the boy recognizable for his enslaver to reclaim him. Compared to other notices that also mention physical characteristics, signs of violence on the body or signs of modification, or color and type of clothes, this one is remarkably laconic.

We will never know what became of this unidentified young freedom seeker. His is one more life story distilled in the ten lines of an advertisement in the Barbados Mercury. While that notice is a record of violence and persecution, it is nonetheless suggestive of the humanity of the young boy found dying alone on a road in Martinique.

View References

[1] The British occupied Martinique primarily between 1794-1802 and 1809-1815. Rebecca Hartkopf Schloss, “”Happy to Consider Itself an Ancient British Possession”: The British Occupation of Martinique,” in id., Sweet Liberty: The Final Days of Slavery in Martinique (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).

[2]The Code Noir granted the enslaved the right to appeal directly to a royal magistrate, although many of these complaints were dismissed and enslaved people were often punished for doing so.

[3] The same ad was also placed in the December 25 issue of the newspaper, hence the date on it.

[4] The National Archives’ Website: Discovery: PROB 11/1327/274 Will of Michael Keane, 30 July 1799, Description available at https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D450619 (accessed 27 November 2024).

[5] Mark S. Quintanilla, “‘From a Dear and Worthy Land’: Michael Keane and the Irish in the Eighteenth-Century West Indies,” New Hibernia Review / Iris Éireannach Nua 13, no. 4 (2009): 59–76. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25660921.

[6] “Michael Keane,” Legacies of British Slavery Database, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146654575.

[7] Mark S. Quintanilla, An Irishman’s Life on the Caribbean Island of St Vincent, 1787-90 : The Letter Book of Attorney General Michael Keane (Chicago, IL: Four Courts Press, 2019).

[8] PROB 11/1327/274.

[9] Marisa Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), 49.