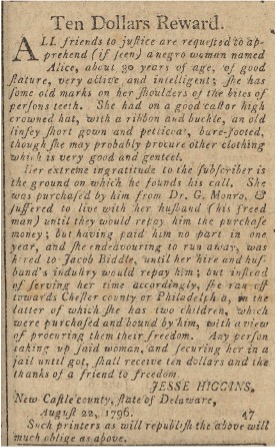

Alice was an enslaved woman who in 1796 escaped from Delaware to what was then the nation’s capital, Philadelphia. Jesse Higgins, the main who claimed ownership of Alice, was particularly upset by Alice’s escape, although the nature of his unhappiness differed from that of other enslavers who were angered by the escape of people they claimed to own. In his advertisement Higgins referred to Alice’s “ingratitude,” for he believed himself to be a friend to enslaved people, and he referred to himself as a “friend to freedom” and a “friend to justice.” Indeed, Higgins devoted a portion of his advertisement to a description of how he had acted in what he believed was Alice’s best interests, allowing her to live with her husband and creating a mechanism for her to purchase her own freedom.

Clearly Alice saw things differently. She was not willing to pay the price for her freedom that Higgins had set. Alice appears to have been an opportunistic and resourceful individual, and Higgins indicated that “she may probably procure other clothing which is good and genteel.” This line suggests that Alice was likely to procure good quality clothing, changing her appearance from the more workmanlike dress provided by her enslaver, and thereby presenting herself as a member of Philadelphia’s free Black community. Higgins may have been implying that Alice was like other freedom seekers and criminals who sought to change their appearance, and he was providing useful information to slave catchers in the Philadelphia and Delaware areas.

Furthermore, the advertisement also described Alice as “very active and intelligent.” It is perhaps a little surprising that the subscriber chose to describe Alice in this manner, as most enslavers used more negative and derogatory language to describe enslaved people. Rather than “intelligent,” more derogatory words like artful and sly were commonly found in advertisements. Perhaps Alice’s escape can be seen as further evidence of her active and intelligent mind. She most likely recognized a chance to escape and possibly had been planning for it. Alice ran away to her children, which would create its own set of challenges beyond an individual escape.

The advertisement described some of Alice’s physical characteristics, including the fact that “she has some old marks on her shoulders of the bites of persons teeth.” However, the advertisement does not specify how Alice had acquired these unusual scars. Perhaps these were the result of a fight, and if so they indicate her willingness to use physical force to defend herself. It seems unlikely that the bite marks occurred due to punishment by an enslaver because this would be a very unusual form of control or punishment, but it cannot be ruled out. Alice was approximately 30 years old when she escaped, so she may have sustained this injury years earlier, perhaps even as a child. Ultimately the cause of the scars is unknown, but they may reflect her strength, or at least her willingness to defend herself.

Perhaps the most unusual part of this advertisement was Higgins references to Alice’s “extreme ingratitude to the subscriber” as “the ground on which he founds his call.” Higgins was a well known and successful man in late eighteenth century Delaware. We do not know how long Alice had been enslaved by Dr. Monro, her previous enslaver, only that Higgins had purchased her from Monro in order to help her toward freedom. Higgins believed himself to be far more progressive than other slaveowners around him. He used terms like “friend to justice” and “friend to freedom” because he believed himself to be a friend to those enslaved, a man who was working to help at least some enslaved people achieve freedom. But he was not giving Alice or her children the freedom that she believed was her’s: he was making her repay what he had paid for her, thus buying her own, and then her children’s liberty. Higgins had hired out Alice and her husband to Jacob Biddle until “they would repay him.” This meant that once the money Alice and her husband earned (or Biddle paid directly to Higgins) equalled the money Higgins had paid for Alice, she would be freed. Higgins saw this as a generous act, but for Alice it was still slavery, and at a time when fewer and fewer Black people in the greater Philadelphia area were enslaved. When Alice ran away Higgins interpreted this as betrayal because he believed that he was helping her. But however generous Higgins believed himself to be, Alice clearly saw things very differently. He was not giving her freedom, but rather allowing her to buy it, making her and her husband work for years, sometimes separated from her children.

After Alice ran away from Biddle, Higgins believed that she was heading towards Philadelhia or Chester County, Pennsylvania. This was not surprising, given that her children were in the former location, and because Philadelphia in the 1790s was home to the largest free Black community in the nation as slavery began slowly to wither away in the city and state. Consequently freedom seekers from the Middle Atlantic and the Upper South often headed towards Philadelphia, and this was surely one factor in Alice’s decision to head towards the city.[1] While we cannot know whether she had connections to Philadelphia or not, she probably received advice or information from other Black people, both enslaved and free.

Alice may have collected her children and then taken them with her. This does not appear to be escape on a whim, but rather a carefully planned attempt to unite her family in freedom. The advertisement reveals only what Alice may have done after escaping, but we cannot know for sure. Alice’s drive to obtain her freedom demonstrates her strength and perseverance during the uncertain times following the Revolutionary War. While Northern states were beginning to gradually abolish slavery, Alice was still enslaved. She saw an opportunity to claim her independence with her children and she seized her chance. If her escape was successful, it is likely she stayed in Philadelphia and found community among the large number of African Americans residing in the city.

View References

[1] Billy G. Smith, and Paul Sivitz, “Identifying and Mapping Ethnicity in Philadelphia in the Early Republic,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 140 (2016): 393–411; Billy G. Smith, “Mapping Inequality, Resistance, and Solutions in Early National Philadelphia,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 110 (2021), 207-229.