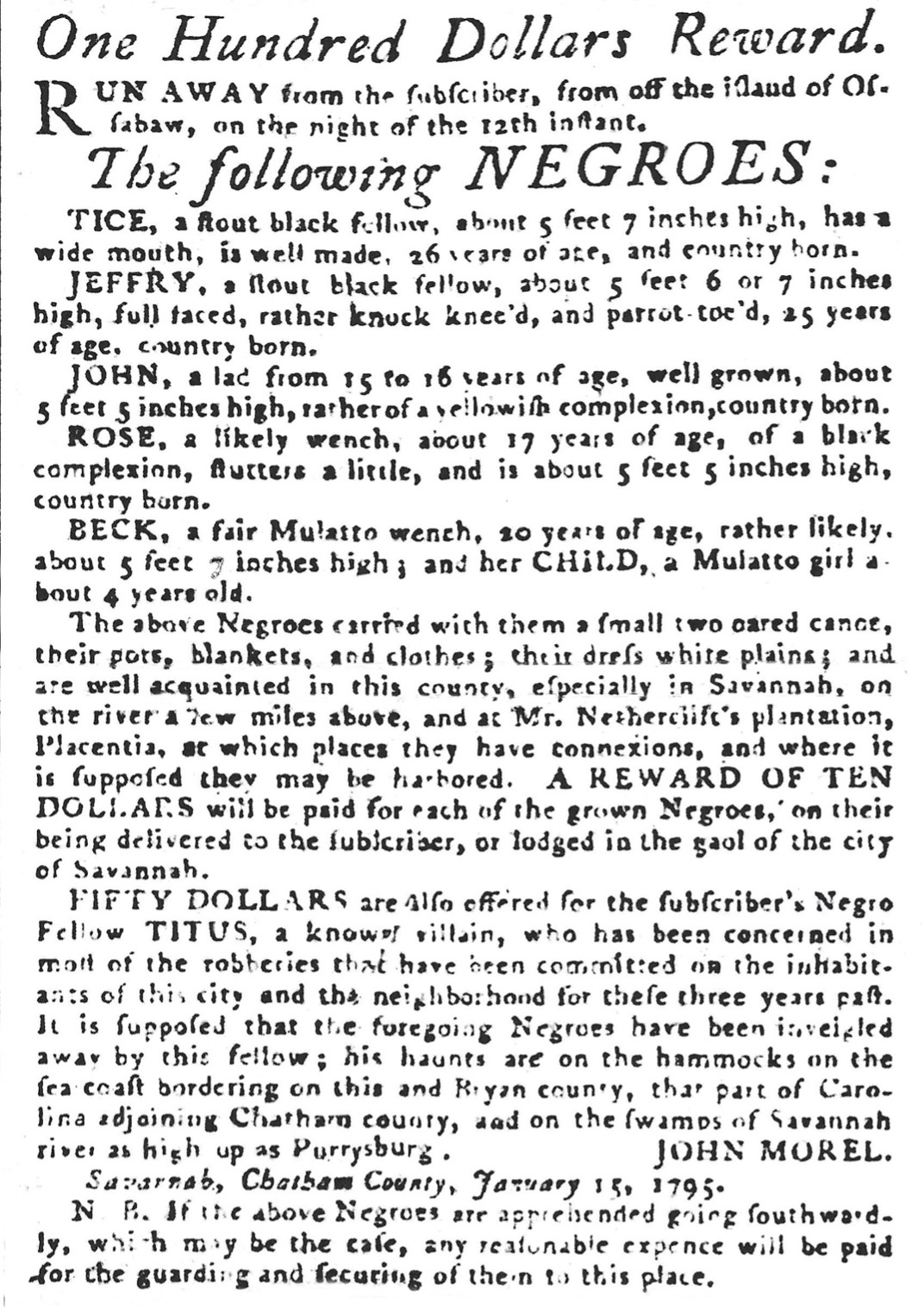

On the night of January 12, 1795, seven individuals escaped from a Sea Island cotton plantation on Ossabaw Island in a small two-oared canoe with pots, blankets, clothing, and, as it turned out, a shotgun and a rifle, and made it to Amelia Island, the northernmost point of Spanish East Florida. They expected to find space to create new lives in a colony that, despite its formal withdrawal of the offer of sanctuary in 1790, rarely returned fugitives to the United States.

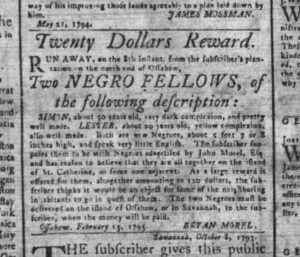

Their leader, Titus, was born on Ossabaw and a maroon of long-standing. He had escaped to Florida in 1789, enjoyed three years of freedom, then been captured and returned to his enslaver, John Morel. In a matter of months, he escaped once more and became a salt-water maroon, travelling up the Ogeechee River and the Savannah River, resupplying himself with rice and other food from the friendly enslaved population, and occasionally stopping on Ossabaw to visit family and friends or so we assume.[1]

His former enslaver was the son of one of the wealthiest men in pre-revolutionary Georgia, with three indigo plantations, a large herd of cattle, and a shipyard on Ossabaw Island. After the Revolution, he incurred heavy debts as he shifted to Sea Island cotton, pursued a reckless lifestyle, and soon faced bankruptcy. In the fall of 1794, Morel made plans to sell part of his holdings of men, women and children, including relatives and friends of Titus.[2]

A master of coastal maritime culture, Titus made the decision to give up his life of freedom and rescue as many of his kin as he could in a bold escape to Florida. The fully loaded canoe that slipped away on the night of January 12 met another craft with other freedom seekers, a total of fourteen people, including those from plantations on other barrier islands and the mainland. He guided the canoes through the marshes behind the barrier islands that dominated the coast.

Stepping out of the craft on Amelia Island were seven men – Titus, Tice, who may have been the brother of Titus; Jeffrey and John; Lester, Summer, and Mingo. Five women accompanied them: Beck, Sue, Nelly, and Betty; and three children, Bess, Elsey, and Phoebe.[3]

Seven individuals came from the plantations of John Morel while two, Lester and Summer, were “New Negroes” from Bryan Morel’s nearby estate. Nelly, whose master was not a Morel, was the wife of Titus as well as the mother of their child Phoebe. Most of the freedom seekers were in their twenties and “country-born.” Tice was accompanied by his wife, Betty. Beck was described as “a fine Mulatto wench” with a mixed-race child. The presence of women and children harked back to revolutionary times when the confusion and chaos of the war created opportunities for whole families to flee, an indication of the strength and depth of feeling that animated this unusually cohesive community.

This small band had good reason to expect success. An earlier agreement between the Spanish governor and the governor of Georgia to return fugitives had fallen apart after the first few months and enslaved people continued to find shelter in Florida. Unbeknownst to them, a new agreement had been reached only a few weeks before. The government in St. Augustine was eager to show its good will.[4]

When news spread of the landing of fourteen people on Amelia Island, Spanish troops quickly surrounded them. Their freedom at stake, the fugitives resisted with their rusty weapons, a brief firefight ensured and one of their number was badly wounded. The seven men, five women, and three children were led away to a nearby plantation not far from the military post of San Vincente Ferrer on the St. Johns River.

Shackled, Titus was placed in a dungeon in the formidable Castillo de San Marcos, where he would remain for the next two years. Titus attempted to escape from the Castillo, was caught, and put on half-rations. Some months after this failure, he made a successful effort to break free, a remarkable achievement given the conditions at the fortress-prison. He headed back to the Savannah region at the head of several enslaved people and the creation of a new maroon community. The Georgia state militia dispersed that community but Titus was never caught.[5]

Titus’ exploits cannot be fully understood unless they are placed within the larger movement of African Americans from the Georgia Lowcountry to Spanish Florida across a forty-year span of time. His remarkable ability to traverse the width and breadth of the Lowcountry, cross international borders and seemingly appear and disappear at will, represented an accentuated version of what hundreds of other Black people in this region were doing across a long space of time. His life and those of his companions pose critical questions about the nature of choices that faced freedom seekers operating in a borderland where an imperial colony, a republic, indigenous people, adventurers, filibusterers, African Americans, and outlaws confronted each other.[6]

View References

[1] Paul M. Pressly, A Southern Underground Railroad: Black Georgians and the Promise of Spanish Florida and Indian Country (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2024), 93-112. The notice of John Morel in the Georgia Gazette (February 26, 1795) gives the details of the range of Titus’s movement in Chatham County from 1792 to 1795.

[2] Paul M. Pressly, “The Many Worlds of Titus: Marronage, Freedom, and the Entangled Borders of Lowcountry Georgia and Spanish Florida,” Journal of Southern History 84, no. 3 (August 2018), 565-567.

[3] List of fugitive Negroes fled from Georgia, February 22, 1795, “Correspondence between the Governor and Subordinates on the St. John’s and St. Mary’s Rivers, 1784-1821, January-March 1795,” East Florida Papers, 1737-1858, Library of Congress, MF Reel 51, frame 214. Titus and Betty/Bella were identified as a couple in an accompanying letter; Georgia Gazette, January 22, 1795, “One Hundred Dollars Reward.”

[4] Jane Landers, Black Society in Spanish Florida (Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 1999), 79-81; Jane Landers, “Spanish Sanctuary: Fugitives in Florida, 1687-1790,” Florida Historical Quarterly 63, no. 3 (September 1984), 311-313.

[5] Governor Enrique White to Gonzalo Zamorano, August 8, 1796, reel 26; James Seagrove to Governor Enrique White, July 4, 1797, East Florida Papers, reel 42, Library of Congress; Sylviane Diouf, Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 132-134; Jane Landers, Atlantic Creoles in the Age of Revolution (Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2010), 98-100.

[6] Pressly, A Southern Underground Railroad, 93-181.