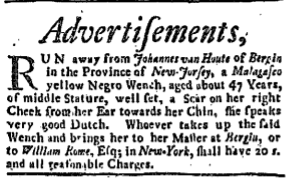

In September 1742 Johannes Van Houte of Bergen, New Jersey advertised for a “Malagasco yellow Negro wench” who was about 47 years old, marked by a “scar on her right cheek,” and fluent in Dutch.[1] Though the advertisement offers few details about her escape, it hints at important aspects of the unnamed Malagasy woman’s life, and in particular her struggle to adapt to an unfamiliar culture under the weight of an oppressive system. It is likely that the unnamed woman originated from one of Madagascar’s coastal regions, frequently targeted by the Merina kingdom, which captured people from other ethnic groups like the Betsileo, Bara, and Sakalava. These people were then sold to European traders who in turn sold them in the Americas.[2] This particular woman quite likely suffered the Middle Passage aboard the Crown Gally, the only known slave ship from Madagascar to arrive in New York between 1700 and 1740. The ship carried 240 enslaved Malagasy people, though only about half survived the grueling journey around southern Africa and across the Atlantic, arriving in New York in 1721. She would have been about 26 years old when she disembarked, and by the time of her escape she had spent 21 years in bondage, nearly half of her life.[3] During these years, at least 17 other ships brought more than 1,900 enslaved Africans to New York (including northern New Jersey), reshaping its demographic and cultural landscape. Bergen County, which lay across the Hudson River from Manhattan, had the highest percentage of enslaved people of all counties in New Jersey, with about one in five residents being enslaved between 1728 and 1820.[4] While living among many enslaved people could have offered some community to this woman, upon her immediate arrival, she would have been set apart by her Madagascan origins, language, and culture.

Madagascar was more than 3,500 miles from Cape Coast Castle on the Gold Coast of West Africa—roughly the same as the distance between London and Philadelphia. Madagascar’s culture, society, and language was significantly different from that of the West Africans who dominated the transatlantic slave trade. Shared rituals, languages, and customs often helped enslaved West Africans connect with one another and resist the dehumanizing effects of slavery. These practices helped maintain a sense of community and purpose in a world that sought to erase them.[5] However, upon her arrival this woman would have been as unfamiliar with the languages and practices of the West African enslaved community as with the world of her Dutch enslavers. This was the isolated and lonely life the enslaved woman would have endured, at least at first.

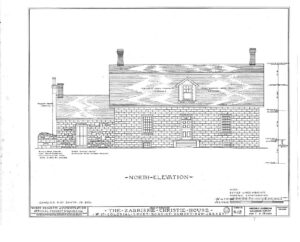

The Van Houte family, the unnamed woman’s enslavers, held significant tracts of farm land in Bergen County, New Jersey.[6] Dutch settlers there were Christian, and their values of frugality and communal labor shaped the community. Homes were typically one story with low ceilings, and small lofts would have been used to store grain, wool, and sometimes divided into sleeping apartments for servants. This unnamed woman likely lived in cramped quarters, possibly above or beside her enslaver’s home, where she had little privacy or autonomy.[7] For the Malagasy woman, the spaces that defined family life and belonging for the European family who enslaved her were separate: she was in their home, but was not truly a family member who belonged.[8]

Her fluency in Dutch indicates a degree of assimilation necessary for survival but also marks a growing distance from her Malagasy identity. The forced labor she performed may have contributed to the scar on her face, or it could have been the result of abuse. Another advertisement from 1734 highlights the range of enslaved women’s labor in Dutch New Jersey, illuminating the kind of work the freedom seeker likely undertook during the two decades before her escape.

To be sold, A Young Negro Woman, about 20 years old, she does all sorts of housework; she can brew, bake, boil, roast, soap, wash, iron & starch; and is a good dairy woman; she can card and spin at the wheel, cotton, linen, and woolen; she has another good property: she neither drinks rum nor smokes tobacco, and she is strong and hale, a healthy wench; she can cook pretty well for roast and boil; she speaks no other language but English; she had the smallpox in Barbados when a child.[9]

The Van Houtes were members of the First Dutch Reformed Church in Hackensack, and this Malagasy woman may well have been influenced by their teachings.[10] Rooted in Calvinist theology, the church emphasized moral discipline, frugality, and communal labor, values imposed upon her. She may have been required to attend services with the Van Houtes, sitting apart from white congregants and exposed to teachings that justified her enslavement. Like the household, the church offered her a position adjacent to rather than fully within the community. Still, the church may have also connected her to a social network of enslaved people working for other Dutch families, offering rare opportunities to create her own community. While church teachings tended to reinforce her status as property, the church may also have provided moments for reflection or quiet resistance, allowing her to reinterpret Christian doctrines in ways that preserved her identity.[11]

We cannot know the reasons behind her escape. Perhaps it was the culmination of years of mistreatment, the pain of separation from members of a family she might have formed, or a longing for freedom and self-determination. Perhaps she sought to join a partner or child, live among a Black community, or simply find peace away from the oppressive environment that had defined her life. What we do know speaks to her remarkable resilience. After being torn from Madagascar, surviving the harrowing transatlantic voyage, and enduring decades of forced labor in an unfamiliar land, she adapted to a society that sought to erase her identity. She learned Dutch, perhaps developed her own beliefs in the framework of the Reformed Dutch Church, and found ways to survive in a system designed to dehumanize her. Her life was defined by this liminal existence, always near enough to see the structures of belonging but never fully allowed entry. Though her name and much of her story are lost to history, her courage in seeking freedom remains a testament to the strength of her spirit and the depth of her humanity.

View References

[1] “Advertisements,” The New-York Weekly Journal, Sept 27, 1742, 4.

[2] Gwyn Campbell, An Economic history of Imperial Madagascar 1750-1895: The Rise and Fall of an Island Empire (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 50-52. Campbell details the political climate and tribes subjected to raids by the Merina.

[3] Given that she was 47 years old, the Crown Gally is the only ship that she could have been on. See Crown Gally, Voyage 75307 in Slave Voyages: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database [accessed December 30, 2024].

[4] Statistics for ships arriving in New York City between 1700 and 1740, drawn from the Slave Voyages database at www.slavevoyages.org [Last accessed December 30, 2024].

[5] Andrea C. Mosterman, Spaces of Enslavement: A History of Slavery and Resistance in Dutch New York (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021), 92-94.

[6] Charles L. Demarest Washburn, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record 28, no. 1 (January 1897), 9-12.

[7] Mosterman, Spaces of Enslavement, 92-94.

[8] For descriptions of Bergin’s early homes and lifestyles, see W. Woodford Clayton, History of Bergen and Passaic Counties, New Jersey (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1882), esp. 35, 46-47.

[9] Quoted in Christopher Matthews, The Black Freedom Struggle in Northern New Jersey, 1613-1860: A Review of Literature (for the Passaic County Department of Cultural and Historic Affairs, 2019), 13. https://www.montclair.edu/anthropology/research/slavery-in-nj/ [Last Accessed December 30, 2024].

[10] Holland Society of New York, Records of the Reformed Dutch Churches of Hackensack and Schraalenburgh, New Jersey (New York: Printed for the Society, 1891), 34.

[11] See Daina Ramey Berry, “Soul Values and American Slavery,” Slavery & Abolition 42 no. 2 (2021), 201-218, 209. See also the Netherlands Reformed Church’s Resources on “Doctrinal Standards & Liturgy.” [Last Accessed: January 13, 2025].