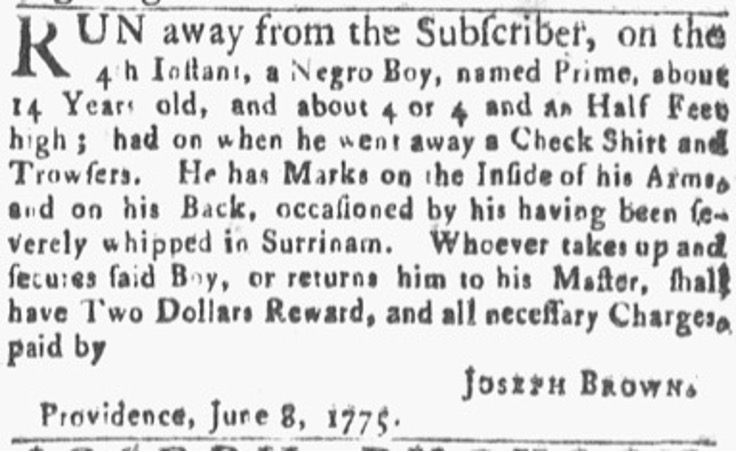

Prime was only about fourteen years old when he escaped, a physically small boy who may not have been in Rhode Island for long. He had come to the colony from Suriname, a Dutch colony in which enslaved people grew and processed coffee, sugar, cotton, and cocoa. Almost 97,000 enslaved Africans were brought to this relatively small colony between 1751 and 1775, and Prime may have been one of these, or maybe he was one of the smaller number of people who was born there.[1] Perhaps Prime had lived and worked in Paramaribo, rather than on a plantation, in the house or workplace of one of the town’s many merchants. Suriname was a particularly profitable colony, which by the mid-eighteenth century may have been producing more wealth per capita than any other.

But the enslaved paid a heavy price, for it was a particularly brutal slave regime. Many enslaved people died, and the plantations prospered only because of a constant supply of newly arrived Africans. John Gabriel Stedman’s journal (1773-7) made the brutality of slavery in Suriname all too clear. Upon arrival in the colony:

the first object I met was a most miserable Young Woman in Chains simply covered with a Rag round her Loins, which was like her Skin cut and carved by the Lash of the Whip in a most Shocking Manner. Her Crime was in not having fulfilled her Task to which she was by appearance unable. Her punishment to receive 200 Lashes and for months to drag a Chain of several Yards in length the one end of which was Lock’d to her ancle and to the other end of which was a weight of 3 Score pounds or upwards.[2]

Stedman bore witness to the singular cruelty of Surinamese enslavers, and of the enslaved he wondered “why in the Name of Humanity should they undergo the most cruel Racks and tortures entirely depending upon the despotic Caprice of their Proprietors and overseers…?”[3]

Did Prime feel fortunate in having been taken away from such a brutal slave society, one in which he had been whipped badly enough to scar his arms and back? Or did he feel isolated, taken away from community and perhaps family, and transported to an unfamiliar place and people, who spoke a language he may not have known? He had become the property of Joseph Brown in Providence, a member of Rhode Island’s leading family of merchants and manufacturers. The Brown family regularly sent ships to the Dutch colony of Surinam, sending horses, tobacco, and various crops from Rhode Island and bringing back molasses, sugar, and on occasion enslaved people. At least six ships arrived in Newport from Surinam during the first six months of 1775, and perhaps Prime had arrived on one of these.[4]

Unlike his brothers Joseph spent no time on the family’s mercantile vessels or as agents elsewhere, and although he managed the family’s spermaceti candle factory he played little role in the Brown’s expansive trading interests. One historian described him as “largely unfitted for mercantile pursuits,” and possessed of a “contemplative, reflective, inquiring mind,” more interested in philosophy and science. The processing of spermaceti into candles may have appealed to Joseph Brown’s scientific interests. Spermaceti, a waxy material found in the cranial cavities of sperm whales, produced some of the finest quality candles, and the Brown’s candle factory in Providence was the largest and most successful in the colonies, and their candles sold throughout the colonies, the Caribbean, and the British Isles.[5]

While Joseph Brown played little direct role in the family’s trade in enslaved Africans and the goods they produced, his predilection for science and more intellectual pursuits did not mean that he was any less implicated in racial slavery. The Rhode Island census of 1774 revealed that while his brothers John and Nicholas each had two Black people in their households, Joseph had four: all were most likely enslaved, and Prime may well have been one of these.[6]

How long had Prime been in Rhode Island when he escaped on June 4, 1775? He appears to have remained at liberty for at least a month, given that Joseph Brown continued advertising for him until July 1. Did this small young boy leave Brown’s household because he felt lost and out of place? Or did he see that he might achieve freedom and a better working situation in a society that would not penalize escape with the violence of Surinamese enslavers? He eloped just over a month after the battle between British troops and colonial militia at Lexington and Concord, and two weeks before the battle of Bunker Hill. It was a period of chaos and uncertainty, with the mobilization of troops and the preparation of ships for battles at sea, and as such it may have been a propitious moment for escape. Did Prime succeed in making a new life for himself, perhaps on board a ship or with either British or Patriot troops? Or was he recaptured, and at least for a while re-enslaved in Joseph Brown’s household? All we can be sure about it that having left the hellish slave society of Suriname, a physically (and probably a psychologically) scarred small young boy dared to seize the opportunity to attempt to escape from his new enslaver in the heart of Providence, as the opening battles of the American War for Independence took place.

View References

[1] Slave Voyages: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyages/r6SfxAS6 [accessed January 30, 2025].

[2] John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative of a Five Year Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam. Transcribed for the First Time from the Original 1790 Manuscript, ed. Richard Price and Sally Price (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988), 140.

[3] Ibid., 171.

[4] James B. Hedges, The Browns of Providence Plantations: The Colonial Years (Providence: Brown University Press, 1968), 29-41. The ships arriving from Surinam were the Harmony, the Sally, the Industry, the Polly, the Freelove, and a second ship named Industry. See Newport Mercury, January 9, March 6, April 10, May 1, May 15, and May 22, 1775.

[5] James B. Hedges, The Browns of Providence Plantations: The Colonial Years (Providence: Brown University Press, 1968), 13, 14, 88-92. See also Christy Mikel Clark-Pujara, “Slavery, emancipation and Black freedom in Rhode Island, 1652-1842” (PhD. Diss., University of Iowa, 2009), 71.

[6] Entries for Nicholas Brown, John Brown, and Joseph Brown, Providence, Rhode Island in Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and providence Plantations, Taken By Order of the General Assembly, In The Year 1774, arranged by John Bartlett, (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), 38.