On October 3, 1776, a “young Negro woman named BET” emancipated herself in Philadelphia from the household of Thomas Stone, a lawyer and planter from Port Tobacco, Maryland, on the Potomac River, a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Because the woman known as Bet made her escape while Thomas Stone was preparing to leave Philadelphia to return to Maryland, it is reasonable to assume that the enslaved domestic refused to travel south with Thomas Stone and his wife, Margaret. In a confluence of events, Bet also took advantage of the rising tension in the Mid-Atlantic as an overwhelming British military force took possession of New York City on September 15, 1776. Wearing a fashionable black alamode (silk) bonnet trimmed with lace on the day of her flight, the housemaid or personal attendant carried enough clothing for several outfits. These garments provided warmth, a form of currency, and perhaps a demonstration of her sewing skills to potential employers. Bet evaded capture into November, and then she drops out of the historical record.[1]

Bet’s clothing signaled her status above a common laborer. In the later eighteenth century, manual laborers generally wore coarse, loose-fitting fabrics while genteel people dressed in finer more close-fitting clothing. Bet’s clothing occupied a broad category in between these two poles. Her new purple and yellow checked jacket and petticoat, for example, was made of a worsted wool fabric called stuff. Women chose stuff because it was durable, warm, affordable, yet had a luster that resembled more expensive fabrics. Bet’s blue jacket and petticoat was made with another shiny worsted wool textile called shalloon. Both stuff and shalloon were a step above plains, a cheaper woolen common among the poor. Bet also possessed a short gown made of calico, a printed cotton that was easier to wash than woolens and more costly than a coarse linen like osnaburg. Her petticoat of bombazine, a smooth weave of worsted wool and silk, was black and very fashionable. Whether Bet’s enslaver issued or passed down these clothes or textiles to her, or Bet purchased them in the city, or a combination thereof, Bet claimed a measure of respect through her dress.[2]

Bet may have intended to sell or barter her clothing to finance her journey into freedom. Philadelphia offered a ready market for used clothing, particularly in late summer 1776 when British-imported dry goods were scarce. As part of a Congressional delegate’s household, Bet was well-positioned to hear conversations about the scramble to procure clothing, blankets, and other supplies for American troops in New York after the British landed over 20,000 troops, including Hessian mercenaries, on Staten Island, accompanied by thirty warships, in July and August. As the fighting spread, Maryland’s provisional government was unable to procure clothing “on any terms,” and Thomas Stone was tasked with purchasing clothing in Philadelphia for a company of Maryland troops. On September 30, Thomas Stone reported on his search in the city: “Every thing here is very dear, but I thought it better to pay high, than keep the soldiers doing nothing [i.e., idle] or send them naked to camp.” High prices in the market likely encouraged Bet to carry all the clothes that she could to support herself.[3]

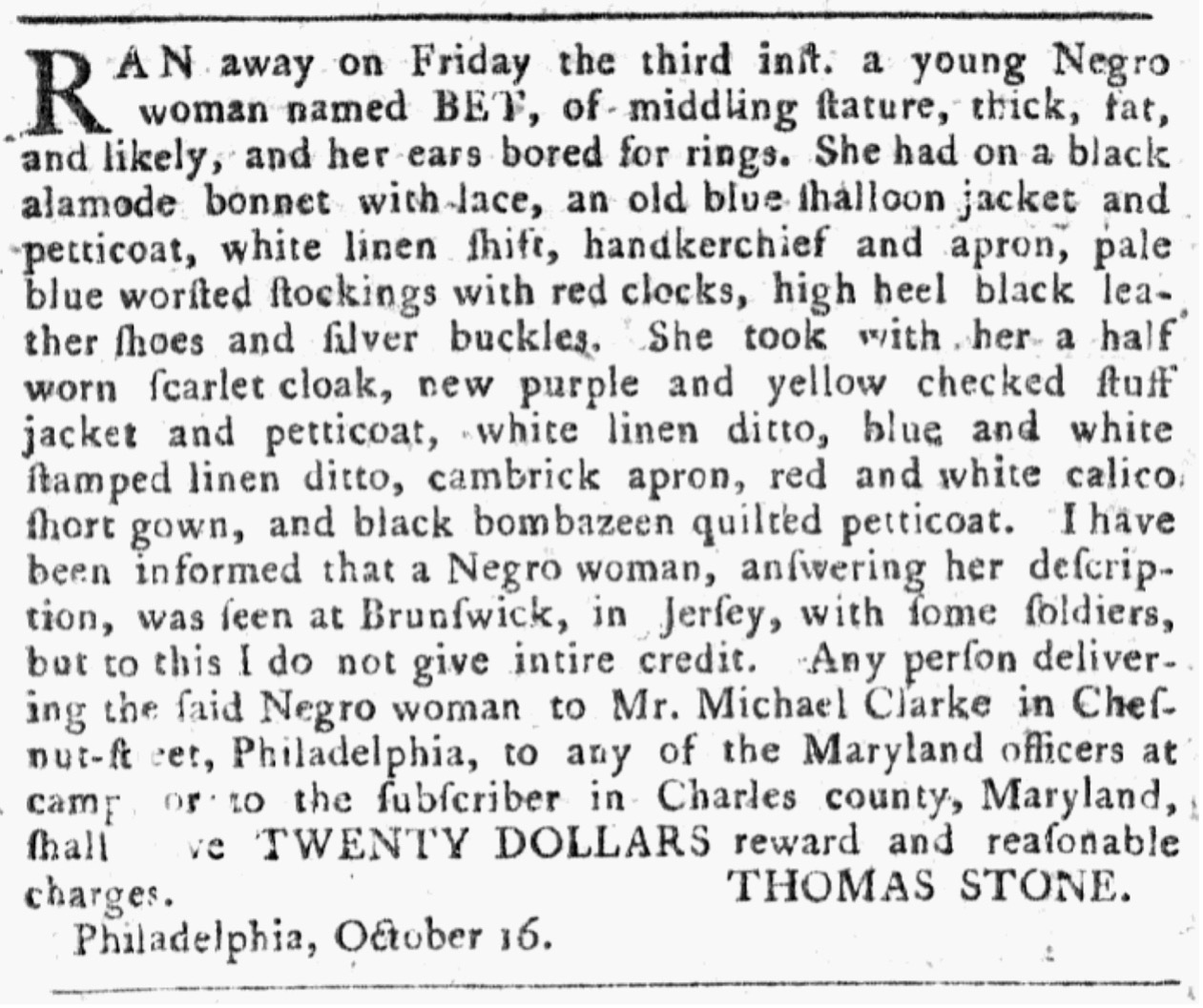

Thomas Stone acted swiftly but discreetly to recapture her. Within two days of Bet’s disappearance, a Philadelphia tavernkeeper named Michael Clark began to place advertisements in city newspapers on behalf of “a gentleman of Maryland.” Michael Clark’s tavern stood across the street from the Pennsylvania State House where the Continental Congress met (now known as Independence Hall). Thomas Stone apparently trusted Michael Clark’s knowledge about goings-on in the city—or believed that Michael Clark could elicit leads from his patrons, hired staff, and servants. “It is supposed she is concealed in this city,” read Michael Clark’s notice for Bet dated October 5. Philadelphia in the 1770s had a free Black population of several hundred people that may have offered Bet a safe harbor. [4]

Nearly two weeks had passed after Bet’s flight when Thomas Stone, his departure for Maryland drawing close, disclosed his name in advertisements for Bet and shared a rumor that she had been seen at “Brunswick, in Jersey with some soldiers.” He notified the public that Bet, upon capture, could be delivered to “any of the Maryland officers at camp” for a reward. Thomas Stone thus expanded his search north of Philadelphia towards British-occupied New York City. Because New York remained the focus of the fighting between the Continental and British armies in mid-October, Stone seems to have been suggesting that Bet may have traveled along a principal route between Philadelphia and New York City that ran through New Brunswick, New Jersey.[5]

All advertisements for Bet appear to have stopped after November 20, the day that the British captured Fort Lee on the New Jersey side of the Hudson, ushering in a new stage of the campaign: we cannot know whether she was recaptured, and perhaps sold as punishment for her escape, or whether her bid for freedom was successful. In mid-December 1776, Congress declared Philadelphia “a seat of war” and voted to remove itself to Baltimore, Maryland. The British army occupied the city nine months later. By then, perhaps, Bet had been able to begin to realize the future she had imagined for herself when she stepped out on that fateful October night.[6]

View References

[1] No adult named Bet, nor any adult with similar names such as Betty and Elizabeth, appear in Thomas Stone’s 1788 probate inventories (Amy Speckart, “New Perspectives on Haberdeventure Plantation in Charles County, Maryland, 1770-1787, Historic Resource Study of Thomas Stone National Historic Site, Port Tobacco, Maryland,” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, February 2022, Appendices 4 and 9, https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2293176).

[2] Linda Baumgarten, What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2002); Sally A. Queen, Textiles for Colonial Clothing: A Workbook of Swatches and Information (Arlington, Virginia: Q Graphics Production Co., 2000); Shane White and Graham White, “Slave Clothing and African-American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” Past and Present, No. 148 (August 1995), 149–86; John Styles, The Dress of the People: Everyday Fashion in Eighteenth-Century England (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2007). Notably, Thomas Stone did not accuse Bet of stealing the clothes, leaving open the possibility that he regarded the clothing as Bet’s possessions. As an enslaved person, Bet did not have a formal right to own property. Anglo-American legal practice, though, recognized the rights of a head of household’s dependents, including the enslaved, to possess and exchange textiles (Laura F. Edwards, Only the Clothes on Her Back: Clothing and the Hidden History of Power in the Nineteenth-Century United States [New York: Oxford University Press, 2022).

[3] Archives of Maryland Online,12: 258 (quote), 291, 311 (quote), 344, https://msa.maryland.gov (accessed November 13, 2024); Julie Flavell, The Howe Dynasty: The Untold Story of a Military Family and the Women Behind Britain’s Wars for America (New York: Liveright Publishing Company, 2021), 218-9.

[4] Michael Clark (also spelled Clarke), tavernkeeper at the Sign of the Blue Ball on Chestnut Street opposite the Pennsylvania State House (now Independence Hall), submitted a notice for Bet on Stone’s behalf dated October 5 that appeared in Philadelphia newspapers from October 9 (Pennsylvania Gazette) until November 9 (Pennsylvania Ledger, or, the Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey Weekly Advertiser). On Clark’s occupation and location, see Anna Coxe Toogood’s “Historic Resource Study, Independence Mall, The Eighteenth-Century Development, Block One, Chestnut to Market Streets, Fifth to Sixth Streets,” Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia, August 2001, pp. 19, 60; entries for Michael Clark, Tavern and Liquor License Records, Historical Society of Pennsylvania; Michael Clark, “Twenty Schillings Reward,” runaway advertisement for an Irish female indentured servant, Pennsylvania Gazette, January 12, 1769. On Philadelphia’s free Black communities in the later eighteenth century, see Gary B. Nash, Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia’s Black Community, 1720–1840 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1988), and Erica Armstrong Dunbar, A Fragile Freedom: African American Women and Emancipation in the Antebellum City (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2008).

[5] The runaway advertisement subscribed by Thomas Stone and dated October 16, Pennsylvania Evening Post, October 19, 1776, also appeared in the Pennsylvania Packet on October 22 and 29, 1776, and in the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser on November 20. Stone left Philadelphia for Maryland by October 24 (Edmund C. Burnett, Letters of Members of the Continental Congress, 8 vols. [Washington, DC: Carnegie Institute of Washington, 1923], 2:l). Congress and its armed forces used New Brunswick, New Jersey, as a stopover between Philadelphia and New York and as a place to gather troops in the summer and fall of 1776. See, for example, P.H. Smith, G. Gewalt, R. F. Plakas, and E. R. Sheridan, eds., Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1775–1789, 26 vols. (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1976–2000), 4:381, 5:129, 130, 137, 159, 453, 561; George Washington to John Hancock, October 5, 1776, and George Washington to William Livingston on the same day, Papers of George Washington Digital Edition (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia Rotunda, 2008), Revolutionary War Series, 6: 474, 482, also 7:161n. On New Jersey as a theater of war in 1776, see Arthur S. Lefkowitz, The Long Retreat: The Calamitous American Defense of New Jersey, 1776 (Metuchen, New Jersey: The Upland Press, 1998), and Leonard Lundlin, Cockpit of the Revolution: The War for Independence in New Jersey (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1940). For a brief overview of the literature about refugees fleeing enslavement in the rebel colonies who sought the protection of the British military, see Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 50–3.

[6] Worthington C. Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, 34 vols. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1906), 6:1027 (quote). Michael Clark, in his October 5 advertisement for Bet, reported that she “went away” in the “evening.” For other stories of enslaved women taking advantage of the social and political upheaval on the Eastern seaboard during American Revolutionary War, see Karen Cook Bell’s Running from Bondage: Enslaved Women and their Remarkable Fight for Freedom in Revolutionary America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2023).