Could Billy, Tom, and Lubin have made it is far as Providence, some 1,500 miles north of Cap Français in Saint Domingue, working their way to the New England port on one of the many ships bringing goods from the Caribbean? Their enslaver clearly thought such an escape was possible, for P.F. Claessens and his North American contacts placed versions of this advertisement in newspapers published in Providence, New London, New York City, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston, all port cities engaged in trade with the Caribbean. Multi-racial crews were constantly sailing into United States ports like Providence, and self-liberated men and boys were included in their crews.[1]

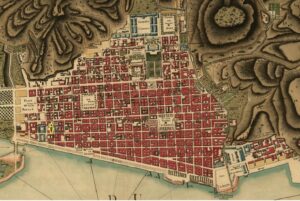

Cap Français was the largest city in the Caribbean’s wealthiest—or greatest wealth-producing—colony. By the late 1780s as many as 15,000 people lived there, about two-thirds of them enslaved, one-tenth free people of color, and the remainder French and other European and North American Whites. The colony boasted a number of large port cities but Cap Français was the largest, handling more than one-third of the prodigious export trade.[2] The United States was a major trading partner of St Domingue. Shedden, Patrick, and Company, the agents mentioned in these North American advertisements, were perhaps the most successful New York City firm trading with the Caribbean. With premises on Water Street, their advertisements offered sugar, rum, and molasses from the Caribbean, tobacco from Virginia and Maryland, madeira from the Atlantic islands, mahogany from central America, and many other goods. Many ships were sailing between St Domingue and North America, and by this time the French colony provided the United States with most of its coffee and much of its sugar and molasses. Often ship captains were desperate for able-bodied sailors, so it is not surprising that Claessens feared that the escapees had joined one of these crews.[3]

This trade was in people as well as in the sugar, coffee and the other goods that they produced. Between 1750 and 1785, more than 350,00 enslaved Africans were brought to St Domingue, and more than half disembarked in Cap Français.[4] Enslaved people from other colonies and the United States were also sent to the city, sometimes expelled and sold because they had attempted escaped or in other ways resisted their enslavement; apparently, these newcomers were disproportionately represented in advertisements for enslaved people who had escaped. Perhaps these people contributed to the simmering discontent among the enslaved in Cap Français and the surrounding area, which would explode into open rebellion in the early 1790s. A report by the French Chamber of Agriculture in 1785 described the town as the center of discontent among enslaved people: “The Negroes are so open in their insubordination that the line of demarcation between whites and slaves has almost vanished. What remains of it can be seen when one journeys away from [Le Cap]. Sooner or later this town is going to cause even greater problems between discipline-loving planters and their workforces.”[5]

Billy, Tom, and Lubin appear to have been typical of the enslaved newcomers who resisted by escaping. All three had come to the island from elsewhere in the Americas, Billy from Charleston, South Carolina, Tom from Jamaica, and Lubin from Dutch Surinam. Their escape was built upon an alliance between men from different places and cultures, united by their resistance to enslavement in the French colony. We learn a little about them from the advertisements placed in North American newspapers, but also from an earlier advertisement published in Affiches américaines in St Domingue in August 1785, shortly after their escape. The notice mentioned “Thom” and Lubin, describing the former as a “Créol anglois,” about 5 feet 4 inches tall, and a carpenter, and the latter as a native of Surinam who was 5 feet 2 inches tall, a cooper and sometime butcher who was scarred both by smallpox and a scar on his leg. The advertisement suggested that the two men had escaped separately, and that both had been seen at different locations outside of Cap Français.[6]

However, a second advertisement, published in the same newspaper almost eighteen months later, mentioned Billy and aligned more closely with the reports of a group escape that had appeared in North American newspapers in late 1785 and early 1786. On December 2, 1786, this advertisement reported that Billy, an Englishman aged about 45, had escaped in a fishing boat with other enslaved people some eighteen months earlier. But unlike the advertisements of a year earlier, which had been published because Claessens feared that Billy, Tom, and Lubin might have found their way onto ships bound for North America, this advertisement suggested that the escapees might have landed their boat near Port-au-Prince in November 1786, more than a year-and-a-half after they had set sail.[7]

Were all three men still free? And if so, what had they been doing, and where had they been for all this time. Eighteen months was time enough for a return voyage to a North American port, or perhaps they had made their way to and from elsewhere in the Caribbean, although landing almost anywhere else risked capture and re-enslavement. Perhaps they had remained at liberty in St Domingue, passing as free, and maybe working as fishermen. Whatever their fates, the traces of Billy, Tom, and Lubin that survive in Haitian and North American newspapers show that however difficult and dangerous it might have been, it was possible for enslaved men to escape from Caribbean islands, and possibly find their way to freedom on the very ships that carried enslaved people and the goods they produced.

View References

[1] “Ran [or Run] away from Cape-Francois,” The Connecticut Gazette; and the Universal Intelligencer (New London), 2 December 1785; Independent Journal (New York City), 2, 5, and 9 November 1785; The Pennsylvania Packet, and Daily Advertiser (Philadelphia), 9 November 1785; Maryland Journal (Baltimore) 18, 25 November, 2 December 1785; The State Gazette of South Carolina (Charleston), 5 January 1786.

[2] David Geggus, “The Slaves and Free People of Color in Cap Français,” in The Black Urban Atlantic in the Age of the Slave Trade, ed. Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, Matt D. Childs, and James Sidbury (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 101-2.

[3]For examples of advertisements, see “For BERMUDAS… SHEDDEN, PATRICK, and Co., Who have for Sale…’” Independent Journal (New York), November 6, 1784; “Shedden, Patrick, & Co… GOODS,” New York Morning Post, July 4, 1786. An example of another firm’s advertisement for goods recently imported from Cap Francais, see “JUST imported in the Brig COMMERCE… from Cape Francois,” Independent Journal (New York), December 15, 1784. For more on Shedden, Patrick, and Company, see Walter Barrett, The Old Merchants of New York City, III (New York: Thomas R. Knox and Co., 1885), 69-71. The scale of the trade between St Domingue and the United States is laid out in Peter Andreas, Smuggler Nation: How Illicit Trade Made America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 71, and Benjamin Grande, “Yankees in Haiti: Boston Merchant Trade in Revolutionary Saint-Domingue,” (MA Thesis, Tufts University, 2016), 46-7.

[4] Slave Voyages: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database [accessed November 20, 2024].

[5] Chambre d’Agriculture report, June 2, 1785, F3/126, fols. 408-10, Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer, Aix-en-Provence. Quoted in Geggus, “The Slaves and Free People of Color in Cap Français,” 119.

[6] “Thom, Créol,” Affiches américaines, Supplement aux Affiches Américaines, (Cap Francais), August 24, 1785.

[7] “Billy, Anglais,” Affiches américaines, Supplement aux Affiches Américaines, (Cap Français), December 2, 1786.