By the spring of 1782 the residents of Rhode Island knew that the war for independence was all but over. It had been three years since the British had abandoned Newport, more than six months since the British surrender at Yorktown, and peace negotiations were underway in Paris. It was at this moment that Pero decided to free himself from service to Joseph Reynolds in Exeter, Rhode Island. We do not know how long Pero had labored for Reynolds. Eight years earlier the Rhode Island census of 1774 had recorded that Reynolds was the head of a household of ten people in Exeter, and one of these ten was a Black man, quite likely Pero. But the township was home to only 78 “Blacks” and “Indians,” who together comprised 4.5% of the township’s total population of 1,864. Having served the Reynolds family for at least the duration of the war for independence, Pero likely thought that it was time for his own independence.[1]

What do we know of Pero? We cannot be sure whether or not he appears in any other surviving records, so we must rely on what we can learn from this advertisement. Reynolds identified Pero as American-born, quite possibly in Rhode Island. Although Exeter was predominantly White, Rhode Island as a whole had a relatively high proportion of Black and Indigenous people. By 1790 the state was home to at least 4,355 Black and indigenous people, and this included sizeable Black and Indigenous communities in some towns, with 640 in Newport, 475 in Providence, 943 in North and South Kingston, and 259 in Warwick. All of these communities were within about twenty miles of Exeter, making them both appealing and accessible to Pero.[2]

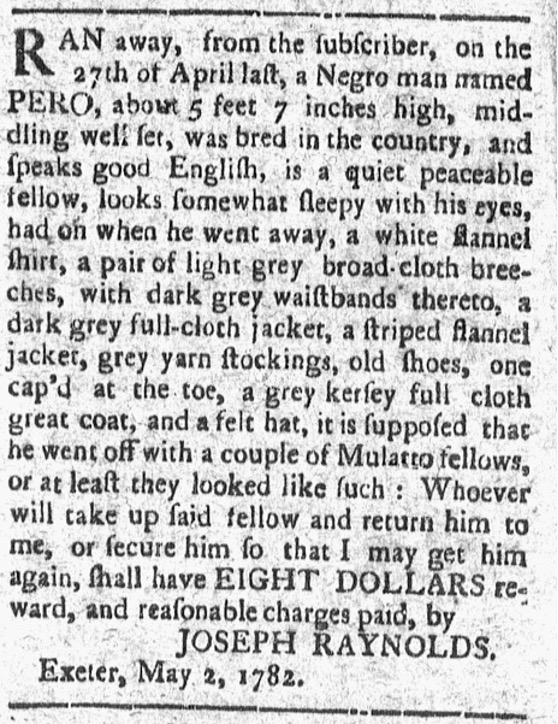

According to Reynolds, Pero was about 5 feet 7 inches tall, spoke English well, and was “a quiet, peaceable fellow, [who] looks somewhat sleepy with his eyes.” Other than specifying that the freedom seeker was a man, Reynolds did not include Pero’s age, and the physical description is fairly minimal. Instead, Reynolds described the clothing that Pero took with him in some detail, apparently believing that this information would be useful in identifying him. It was the clothing of a working man in late-eighteenth century New England, simple and functional. Pero’s leather shoes were old, and one had been patched where the leather had worn through over the toe. Above these, and covering his lower legs, Pero wore grey yarn or woollen stockings, and light grey colored broad cloth breeches, made of a densely woven woollen cloth. His breeches were topped by a dark grey waistband, and on his torso he wore a loose fitting white show, probably tucked into his waistband. Pero took with him a striped flannel jacket, and a larger grey kersey full cloth coat. Both were made of wool, and the fibers of the full cloth kersey coat had been compressed and matted to make a thick, heavy, and water-resistant finish. His felt hat was probably dark in color, likely made of wool and fulled or worked by being pressed to make it solid, water resistant, and able to be worked into the required shape.

Pero may well have sold or exchanged some of this clothing in order to disguise his appearance. But even if he retained them, these clothes were not at all distinctive, and both Black and White working men of this era were wearing much the same. Was the Black population sufficiently large for him to blend in, or was he able to get further away, perhaps joining the crew of a ship in Providence or Newport, or heading north to Boston or south towards New York?

The 1790 Federal census recorded only White people living in Joseph Reynolds’ household in Exeter. Perhaps Pero’s escape eight years earlier had been successful, or maybe Reynolds had granted Pero his freedom. Intriguingly, the census also recorded Pero Potter as the Black head of a household in Exeter containing one other Black person, perhaps his spouse. Might this have been the Pero who had escaped from Reynolds, having taken on a different last name?[3]

View References

[1] Entry for Joseph Reynolds, Sr., in Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Taken by Order of the General Assembly, in the Year 1774 (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), 166. The returns for Exeter are on pages 162-169.

[2] Return of the Whole Number of Persons Within the Several Districts of the United States, According to “An Act Providing for the Enumeration of the Inhabitants of the United States… (Philadelphia: Childs and Swaine, 1791), 3.

[3] Entry for Joseph Reynolds, Exeter, 41; entry for Pero Potter, Exeter, 42, in Heads of Families at the First census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790. Rhode Island (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1908).