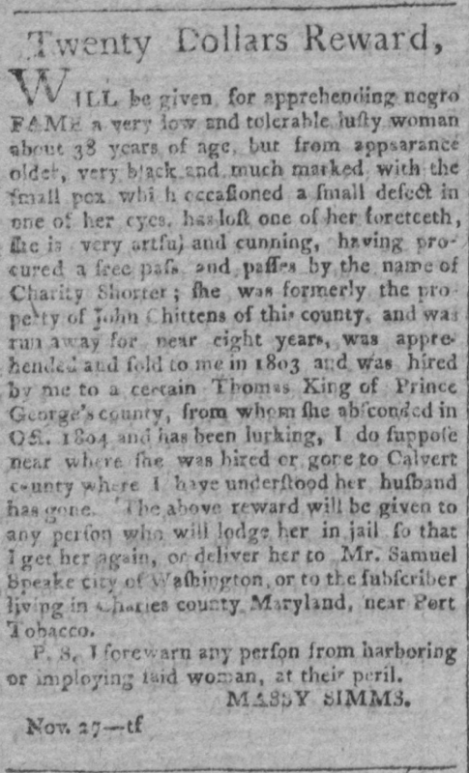

On January 15, 1806, an advertisement appeared in the National Intelligencer seeking the return of an enslaved woman named Fame. The advertisement stated that Fame, who was approximately 38 years old, had escaped from Thomas King of Prince George’s County, Maryland, in October of 1804, over two years earlier. What makes Fame’s case extraordinary is that this 1804 escape marked her second long-term spell of freedom. Fame had previously fled bondage in 1795 and managed to live free for eight years before being recaptured by John Chittens, who then sold her to Massey Simms, who in turn hired her out to Thomas King for the period of one year. Before their agreement concluded Fame orchestrated a second escape. Simms then published an advertisement over forty times between November 23, 1804 and May 5, 1806, in order to “get her again.”[1]

Fame may have had help in escaping. She appears to have acquired several free passes under the name of “Charity Shorter.” This was an astute choice of name, for throughout the Washington D.C. and Maryland area, members of the Shorter family sued for their manumission between the years of 1795 and 1823. Claiming and proving their descent from a free woman by the name of Elizabeth Shorter, the Shorter family were probably quite well known as a free family of color.[2] The suggestion that Fame had assumed the identity of Charity hints at a possible network of collaboration, resistance, and possibly kinship that existed in this area, and maybe Fame was related to or friendly with members of the Shorter family. Other historians have used the supposed relationship between Fame and Charity as evidence of the local networks of resistance that existed between Black women at this time, suggesting that many Black women were “willing to lend their support and quite possibly their literacy and writing abilities for another woman’s escape.”[3]

The maintenance of familial and kinship bonds may well have served as a primary motivation in Fame’s desire for freedom. It took incredible courage for any enslaved person to escape, and resisting and escaping slavery posed a particular threat for enslaved women. Fame’s story and that of countless other women in this period not only demonstrates the strength and tenacity that was required to seek freedom for themselves and their families, but the presence of “gendered resistance … in their quest to escape captivity and to embrace the consequences of freedom.”[4] In discussing the motivating factors that may have influenced Fame’s decision to flee, it is important to analyze the importance of family as well as kinship. We may understand these two terms to be closely related, or even synonyms, but in the context of early American slavery, kinship can also be a useful reminder that enslaved people utilized particular networks in fashioning their senses of solidarity and community. As historian Tera Hunter explains, “kin networks had to be reconstituted from fractured pieces left behind or formed out of newly arriving individuals. Slaves searched for surrogates to make up for missing loved ones, giving greater emphasis to extended and adoptive familial strategies.”[5] Fame’s connection to her family, as well as the network she formed with the Shorter family highlight the role familial as well as kinship and friendship bonds played in her search for freedom.

Several first-hand accounts of slavery help document that the maintenance of family connections and ties to children often motivated enslaved women, not only in efforts to secure individual freedom, but also to reconnect with lost relatives. In her autobiography, abolitionist Harriet Jacobs explained, “I had a woman’s pride, and a mother’s love for my children; and I resolved that out of the darkness of this hour a brighter dawn should rise for them. My master had power and law on his side; I had a determined will. There is might in each.”[6] This courage and determination exhibited by Jacobs quite possibly reflects similar sentiments exhibited by Fame in her quest for freedom.

One aspect of Fame’s story, however, also appears to set her apart from the more common experiences enslaved women had: she escaped alone. The advertisement which appeared in the National Intelligencer made no mention of anyone she might have been traveling with, only that she may have absconded to reunite with her husband. In many circumstances it was common for women to escape as members of groups, consisting either of family members or other community members. This is in part due to the limited independent mobility and familial responsibilities many enslaved women experienced, and also the extreme danger they faced at the hands of white men. Perhaps Fame was willing and able to escape and face these risks not only because of her connections with free individuals like Charity Shorter, but because she was fleeing in search of her family, perhaps including her children.

According to Massey Simms, Fame was likely around 30 years old at the time of her first escape in 1795, raising the possibility that she may have had one or more children. According to the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, “enslaved women tended to give birth to their first child at a relatively young age and have short intervals between births…because of the pressures placed upon women by slaveholders who were ever-anxious to keep their slave population increasing without the purchase of new people.”[7] While enslaved men were commonly sold alone, mothers and infants were often sold together. However, it is important to note that older children were often separated from their mothers, creating the context which might have propelled Fame to flee enslavement in 1795, and again in 1804. Did she leave children behind when she escaped, or was she trying to return to her husband and children elsewhere? Was her husband enslaved, or a free man? We cannot know.

The desire to reunite with her husband likely animated Fame’s second pursuit of freedom in 1804. Simms admitted as much when he suggested that Fame may have fled to Calvert County, Maryland in search of him. We do not know if she had married him when she was enslaved, or during the eight years when she was free. Marriages between enslaved persons or enslaved and free people in this period were common, although complicated given their lack of legal standing. Because enslaved persons at this time were not recognized as individuals with substantive legal rights, but rather as property, any marriages they entered into were not legally recognized. However, these marriages were important to enslaved persons as a form of resistance and in an effort to reclaim some semblance of personal autonomy, and to make real their own choices in creating families.[8] In some circumstances a husband, wife, and children belonged to the same enslaver and lived on the same plantation, however in many cases these families were separated, and clearly this was at least partly the case for Fame. Financial incentives and the deliberate effort to “blunt the development of affection” between enslaved persons and their children, as noted by Frederick Douglass, were common justifications for familial separation.[9] Through this lens of systematic destruction of family bonds, we can better understand Fame’s motivation for escaping bondage twice over the course of more than ten years.

Fame’s story highlights several key themes in the lives of female freedom seekers: the role family ties had in motivating escape; the gendered differences which were experienced by enslaved persons; and the Black networks of support that occasionally helped aid in escape. To secure their personal freedom, women often had to employ strategies and devise plans that “went beyond the bold actions of their male counterparts.”[10] Fame’s story is remarkable for several reasons, foremost being that the flight detailed in these advertisements was her second escape, with her first lasting an awe-inspiring eight years. Additionally, the ads published over forty times across a two-year period highlight both the familial and kinship connections that likely motivated and supported Fame’s pursuit of freedom, helping her avoid detection and remain free. Indeed, these same networks may have helped her remain free for eight years after her earlier escape. While factors such as limited mobility, lack of geographical knowledge, and familial responsibilities have been identified as reasons many enslaved women did not seek to escape slavery, Fame’s story and that of countless other women highlight evidence to the contrary.

View References

[1] The content of the advertisement in the National Intelligencer remained basically the same, and Simms made only two minor adjustments to its language, the first version being published in November of 1804, and a slightly altered version in February of 1805.

[2] William G. Thomas III, et al., O Say Can You Say: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. http://earlywashingtondc.org [Accessed April 21, 2025].

[3] Tamika Y. Nunley, At the Threshold of Liberty: Women, Slavery, and Shifting Identities in Washington, D.C. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 46.

[4] Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, “Coerced but Not Subdued: The Gendered Resistance of Women Escaping Slavery,” in Mary E. Frederickson and Delores M. Walters, eds., Gendered Resistance: Women, Slavery, and the Legacy of Margaret Garner (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 50.

[5] Tera W. Hunter, Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriage in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017), 29.

[6] Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (New York: Dover, 2001), [1861] 130.

[7] “Motherhood and Children,” Lowcountry Digital History Initiative. https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/hidden-voices/enslaved-women-their-families/motherhood-and-children [Accessed April 21, 2025].

[8] Marriage between enslaved persons throughout this period demonstrates the complexity of this sphere of American society. While marriage and family was seen as a form of liberation and emancipation for enslaved persons, it was also occasionally encouraged by slave-owners to dissuade them from escaping. This notion in itself highlights what historian Tera Hunter refers to as “an institution defined and controlled by the superior relationship of master to slave.” In this circumstance, marriage was re-shaped by enslaved persons to reflect their personal affections and social bonds, while simultaneously controlled by slave-owners. Hunter, Bound in Wedlock, 6.

[9] Heather Andrea Williams, “How Slavery Affected African American Families,” National Humanities Center. https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/freedom/1609-1865/essays/aafamilies.htm [Accessed April 21, 2025].

[10] LaRoche, “Coerced but Not Subdued,” 51.