Block Island lies in Rhode Island Sound, about nine miles south of mainland Rhode Island and fourteen miles east of Long Island. Just under ten square miles in size, Indigenous inhabitants knew the island as Manisses, and today their Niantic, Narragansett, Wampanoag, and Pequot descendants are known as the Manissean people. By 1774 the island was home to 75 families or households, comprised of 469 White, 51 Indigenous and 55 Black people. Many members of the non-White population, like Timothy, were enslaved. Fishing and agriculture were the mainstays of the island’s population, and most enslaved people likely labored alongside White inhabitants in their households or out farming and fishing.[1]

We do not know exactly how many enslaved or bound people of color were members of Abel Franklin’s household, but there appear to have been several. Surviving records include references to an enslaved “Negro man” named “Young Sip,” and a mixed-race woman named “Brigget” Franklin. Timothy was most likely one of several unfree people laboring for Franklin. He had come to the family at about the age of 15 when Caleb Littlefield bequeathed him to his daughter Lydia, Abel Franklin’s wife. Littlefield may have been one of the island’s largest enslavers, as at his death he bequeathed 12 enslaved people to his children and grandchildren. Lydia inherited both Timothy and Martha. It is unclear whether or not these two people were related to one another.[2]

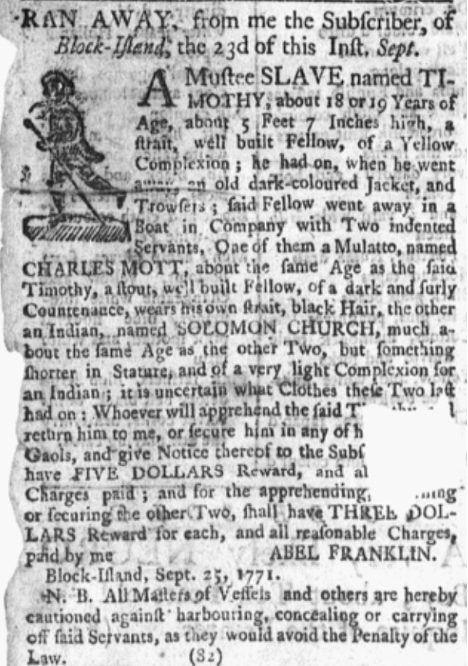

Described in Franklin’s advertisement as “A Mustee SLAVE,” Timothy appears to have had both Indigenous and African ancestry, but we do not know the precise details of his parentage and early life. Nor do we know from which Indigenous community Timothy was descended. He escaped from Franklin’s household with two others, both indentured servants rather than enslaved men, a “Mulatto” man named Charles Mott, and an Indigenous man named Solomon Church. The three embodied the racial diversity of Block Island’s small non-White community.

Timothy’s initial bid for freedom failed and soon he was back with Abel Franklin, at least for a while. However, less than three years later he escaped again, and on March 28, 1774, a second advertisement sought his recapture. This time Timothy was accompanied by “a Negro fellow named Dick” who had eloped from John Paine.[3] Neither the 1771 nor the 1773 advertisement reveals much about Timothy. The first described him as about 18 or 19 years old, five feet seven inches tall and “a strait, well built fellow of a Yellow Complexion,” wearing an old dark-colored jacket and trousers. Three years later the notice indicted that he had grown to a height of five feet ten inches, was “strong built” with curled hair, small legs and big feet, and that he spoke English fluently. On both occasions his clothing was unremarkable, and much like the clothing worn by most working men on the island.[4]

Remaining at liberty on Block Island would have been difficult, and the fact that Franklin advertised for the freedom seekers in Newport newspapers indicates that he expected them to try and escape to Newport or the nearby mainland, both home to significant free and enslaved Black communities. It may have been possible to steal small boats, or even to have previously found and secreted such craft in preparation for an escape. In 1766 Abel Franklin advertised that he had found “two canoes,” offering to return them to their rightful owner, and four years later he published a similar notice for a long boat “in a shatter’d Condition” that he had recovered. Clearly there were small boats to be found, as well as others that might be stolen.[5]

For escapees, timing could be everything, and the imperial crisis had brought chaos and confusion to Block Island. Guarding the approaches to Newport and to Long Island Sound, and from there access to New York City itself, Block Island was vulnerable to assault by the Royal Navy. In August 1775 the Rhode Island assembly confiscated much of the island’s livestock, determined to keep these precious supplies out of British hands. Five months later a British force assaulted the island, plundering and destroying many buildings, including Abel Franklin’s home. The chaos and upheaval of conflict, and the recruitment of young men by British and American armies and navies offered opportunities to many young male freedom seekers.[6]

Abel Franklin died in 1775. The 1790 federal census recorded ten White people in the household of his eldest son John, but no people of color, either free or enslaved. Was Timothy back on Block Island but now living free, or had he escaped and made a life for himself elsewhere? Either way, if he was still alive, he was almost certainly at liberty. The war had provided plenty of opportunities, and it is certainly possible that he had found freedom by joining either the American or British armies, or by signing aboard a privateer or other ship. But it is also possible that Timothy remained on or returned to Block Island, eventually living as a member of the island’s small yet significant community of free people of color. The 1790 census revealed that 15% of New Shoreham’s population was non-White, a substantial minority. To this day the Manissean people of Block Island are racially heterogenous, a living testament to their diverse ancestry and heritage. Perhaps Timothy’s descendants are numbered among them.[7]

View References

[1] See “Timothy,” in Stolen Relations: Recovering Stories of Indigenous Enslavement in the Americas” https://stolenrelations.org/referents/b733f9fe-927e-4978-b676-e99228816e10/ [accessed May 28, 2025]. Entry for New Shoreham, then the name commonly applied to Block Island, in Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and providence Plantations, Taken By Order of the General Assembly, In The Year 1774, arranged by John Bartlett, (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), 239. For the Manissean people today see “Manissean Tribe,” https://manisseantribe.com [accessed March 24, 2025]. For more on the society and economy of seventeenth and eighteenth-century Block Island see S.T. Livermore, A History of Block Island, From Its Discovery in 1514, To the Present Time, 1876 (Hartford, Conn.: Case, Lockwood & Brainard, 1877), 20-43.

[2] Record of Young Sip’s sentencing to 25 lashes for getting Sarah Trim pregnant, “At a Meeting of the town Council of New Shoreham… April 6, 1762,” and “Whereas Brigget Franklin…,” April 6, 1762; record of Caleb Littlefield’s bequest of Timothy to his daughter Lydia Franklin, and Littlefield’s bequest of other enslaved persons, reproduced in Jeffrey Howe, The History and Genealogy of Descendants of Slaves and Indians from the Island of Manissee, Block Island (Riverside, Rhode Island, 1997), 42-3, 86, 83-6 https://drive.google.com/file/d/1zHOPmOLB6PHZGrjplHeTqUKKb2Femydg/view?pli=1 [accessed March 24, 2025]. For the genealogy of Abel Franklin and Lydia Mott Littlefield, who were married in New Shoreham on October 14, 1741, see entry for Abel Franklin, Jr., Family Search, https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/LBCC-MH5/abel-franklin-jr-1719-1775 [accessed March 25, 2025].

[3] “Thirty Dollars Reward. Ran away from the subscribers, in New Shoreham, a Negro fellow named DICK, and a Mustee, named TIM,” Newport Mercury (Newport, RI), March 28, 1774.

[4] “RAN AWAY, from me the Subscriber, of Block-Island… A Mustee SLAVE named TIMOTHY,” Newport Mercury (Newport, RI), September 30, 1771; Thirty Dollars Reward,” Newport Mercury (Newport, RI), March 28, 1774.

[5] “TAKEN up at New-Shoreham, by Abel Franklin, two Canoes,” Newport Mercury (Newport, Rhode Island), January 28, 1766; “A LONG-BOAT, now in Possession of the Subscriber,” Newport Mercury (Newport, Rhode Island), February 12, 1770.

[6] “NEWPORT, December 11. About one o’clock yesterday morning… upwards of 200 marines, sailors and negroes, [landed] at the East-ferry, [Block Island],” The New-York Gazette; and the Weekly Mercury (New York), December 18, 1775. Reprinted The Pennsylvania Evening Post (Philadelphia), December 19, 1775, and other newspapers across the colonies. For the impact of the Revolutionary War see Livermore, A History of Block Island, 88-106.

[7] Entry for “John Franklin,” New Shoreham Town, and total population for New Shoreham, in Heads of Families At the First census of the United States Taken in the Year 1790. Rhode Island (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1908), 18, 9; “Manissean Tribe,” https://manisseantribe.com [accessed March 26, 2025].