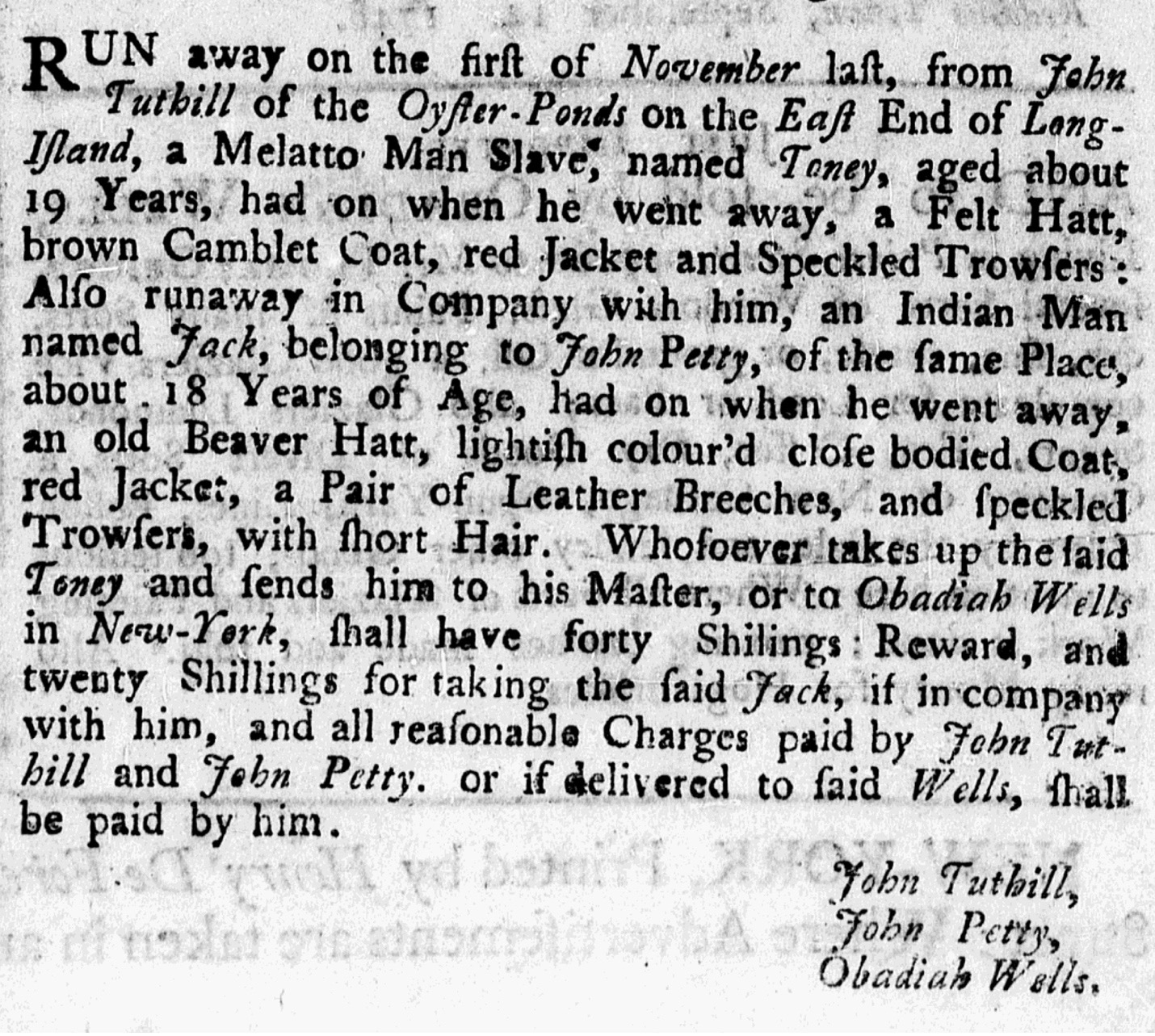

On the first of November, 1748, two freedom seekers fled from the east end of Long Island. Toney, a nineteen-year-old “Melatto Man Slave,” and Jack, an eighteen-year-old Indigenous man, left behind the homes of their enslavers, John Tuthill and John Petty, disappearing into the cold autumn winds. Their absence did not go unnoticed. Within weeks, their names and descriptions were published in The New-York Evening Post, marking them as fugitives.[1]

By the early 1700s, Southold,(a town close to Oyster Ponds on Long Island) had become a well-established settler community. According to local historians, the Tuthills, Toney’s enslavers, had held land in the region since at least 1687.[2] Slavery was integral to the economy and daily life on Long Island. In fact, New York, which included Long Island, was home to the largest enslaved population of any northern colony.[3] By 1698, Southold, included 41 enslaved individuals among its residents. Slavery assumed a particular form on the East End of Long Island. Most households enslaved one or two people, meaning that men like Toney and Jack lived and worked in proximity to their enslavers, rather than within a larger enslaved community. Enslaved people worked in agriculture, fishing, and skilled trades, as well as undertaking household and domestic work.[4] Though they worked under the constant scrutiny of their enslavers, many of the region’s enslaved people were mobile, often traveling alone or between households with little immediate supervision.[5]

This advertisement offers a glimpse into the bonds of solidarity that could form between enslaved Black and Indigenous people. In this case, we see a relationship that defied the imposed racial categories and even likely aided their escape. While the relationship between the enslavers is unknown, it seems clear that Jack and Toney knew each other well enough to escape “in company” with each other. We can only speculate as to how they knew each other, but their clothes serve as a clue. The advertisement describes Toney’s and Jack’s clothing in detail. Toney wore a “felt hatt, brown camblet coat, red jacket and speckled trousers,” while Jack had an “old beaver hatt, lightish colour’d close-bodied coat, red jacket, leather breeches, and speckled trowsers.” Such clothing was quite expensive. Camblet, for instance, was a high-quality woven fabric. Leather breeches and beaver hats were also high quality items. These were not field clothes, suggesting that neither of the freedom seekers were agricultural workers, and they may well have undertaken work that brought them into contact with one another, while working alongside their enslavers.[6]

As an Indigenous man on Long Island, Jack would likely have been a part of the Algonquians of Northeast Long Island, as neighboring parts of Connecticut and Rhode Island. This included several groups such as the Montaukett, Shinnecock, Manhanset, and Corchaug, which were part of the larger Eastern Algonquian linguistic and cultural group. Though these groups shared roots with other Algonquian-speaking peoples, Long Island’s Indigenous communities developed distinct regional identities due to geographic and social factors. Their closest cultural ties were with tribes in Southern New England rather than with those to the west in New York. During the colonial period, the Long Island communities were recognized collectively as the Paumanoc confederacy. They maintained partially mobile lifestyles, which helped preserve shared cultural practices and facilitated interaction with neighboring Indigenous nations, including some Iroquoian-speaking groups. Despite pressures from European colonization, these communities retained strong inter-tribal relationships and continued to adapt their social and political structures in response to changing circumstances.[7]

Jack and Toney’s decision to flee was shaped not only by their courage but also by the broader conditions that made escape both imaginable and possible. First, their age matters, as young men of 18 and 19, they were physically able and at a transitional age of adulthood, making them the most likely to escape.[8] Only a few years earlier, when Jack and Toney were 11 and 12 respectively, they would have heard news of a conspiracy in New York City that included eight fellow enslaved Long Islanders.[9] While White Long Islanders were not necessarily worried about slave uprisings, rumors of enslaved people trying to overthrow their enslavers in nearby Manhattan led to suspicion and prejudice, and a tightening of controls of the enslaved.[10] Raised in this period of heightened repression, Tony and Jack would have grown up knowing the constant threat of violence, mistrust, and the risk of being caught should they escape.

Jack and Toney were categorized according to the racial divides that shaped colonial society in the 18th century. Colonizers viewed enslaved Africans and Indigenous peoples as separate groups, a distinction made clear in the advertisement itself: Toney is labeled a “Melatto Man Slave,” while Jack is described as an “Indian Man.” These labels point to the perspective and control of their enslavers. But here, we can consider a different question: in their shared experience of enslavement, how did they view each other? This advertisement gives us the rare opportunity to consider their relationships.[11] Their friendship, or at least collaboration, shows that relationships were built despite racial classification and the conditions designed to isolate them. Fleeing together, Toney and Jack challenge their enslavers’ insistence on difference.

They may have fled to an Indigenous community, perhaps Jack’s community, to the “unsettled” west, hiding in New York City, or one of the surrounding colonies. Perhaps they ran away by sea. Long Island’s maritime geography of coves and inlets aided some enslaved people in their pursuit of freedom.[12] Did they make it? While these answers are unknowable, we can hold onto this moment of companionship and imagine what it took for two vulnerable teenagers to disappear together. Their flight is all we have, but it reveals the enduring solidarity of this act of resistance. Through this story, we see the buried histories of Black and Indigenous life on Long Island as people who imagined freedom together.

View References

[1] New-York Evening Post (New York, New York), no. 186, December 12, 1748.

[2] Southold (Long Island, N.Y.), Southold Town Records, vol. 2, ed. J. Wickham Case (New York: S.W. Green’s Son, 1882), 71. https://archive.org/details/southoldtownreco02sout/page/70/mode/2up?q=1687 [Last accessed June 1, 2025].

[3] Southold New York Town Government, “Slavery in Southold.” 2, available at https://southoldtownny.gov/DocumentCenter/View/5995/Slavery-in-Southold-African-and-Indian?bidId= [Last Accessed May 23, 2025].

[4] “Slavery in Southold.” 2.

[5] Richard Shannon Moss, Slavery on Long Island: A Study in Local Institutional and Early African-American Communal Life (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1993), 156.

[6] “Slavery in Southold,” 1.

[7] Katherine Howlett Hayes, Slavery before Race: Europeans, Africans, and Indians at Long Island’s Sylvester Manor Plantation, 1651–1884 (New York: New York University Press, 2013), 18.

[8] Moss, Slavery on Long Island, 181.

[9] Moss, Slavery on Long Island, 196.

[10]“Slavery in Southold,” 2.

[11] Hayes, Slavery Before Race, 3. In the introduction, Hayes points out that the enslavers’ viewpoints on race are far more accessible than enslaved peoples’ understandings of race.

[12] Moss, Slavery on Long Island, 178.