Norton Minors fled slavery in St. Croix and traveled nearly 1,800 miles to his birthplace in northern Massachusetts. A ship carpenter and caulker like Minors could have found work in port cities up and down the East Coast. He had escaped a Caribbean death trap to come back to Newbury for a reason. Perhaps he wanted to reestablish kinship ties that gave him a sense of belonging. What did Minors feel when he stepped foot in Massachusetts again? Fear? Anger? Relief? Minors grew up around Newbury’s waterfront where he learned a trade, before being sold to the Caribbean. Unlike many who faced this fate, Norton survived, returned to New England, slipped out of a slave catchers’ grasp, joined the American Revolution, and bore seven sons with a woman named Mary. From fragmented records he appears as a self-determined man, though likely had help protecting his fragile freedom. May he appear someday in a historical document to tell the full story in his own words.

Minors was born as “Norton” around 1723 to an approximately 26-year-old enslaved woman named “Mariah.” She brought him in 1728 to Queen Anne’s Chapel in Newbury, Massachusetts, to be baptized along with herself.[1] How and when Minors got his surname and what it meant to him is a mystery. Perhaps it came from his father, who remains unknown. Mariah and Norton lived in the house of Richard Brown, who made his money trading around the Atlantic. In his 1730 will, Brown included a condition to release Mariah and Norton from bondage if he and his wife Mary died.[2] Brown died a few years later when he was probably in his late 50s and Mary was about 24.[3] Mary remarried 40-year-old Captain Daniel Marquand, another merchant trader.[4] She could have met him at the Episcopal Church where he became warden and then vestryman in the 1740s.[5]

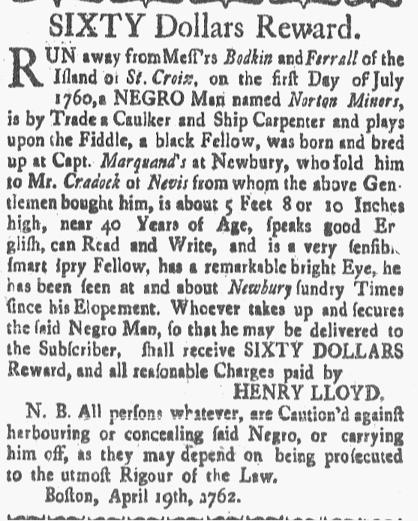

By then Daniel did a thriving trade with the Caribbean on ships he captained and announced in the Boston Post Boy.[6] Under coverture Mary’s property transferred to Daniel. If Richard had paternalistic feelings toward Minors as a boy, Daniel appears to have viewed him through the credit and debit sides of his accounting books.[7] Daniel had ideas for how young Norton could help his business. Minors probably learned caulking and carpentry around this time. Like many other Black New Englanders, Minors could read and write. As one advertisement put it, he was “a very sensible, smart, spry Fellow” with a “remarkable bright Eye.”[8]

Marquand sold Minors to a “Mr. Craddock of Nevis,” a critical event without satisfying answers for questions like when, where, or why.[9] To sell someone as skilled as Minors suggests Marquand’s business might have been faltering.[10] Or had Minors challenged Marquand’s authority? Regardless of the intent, sale to the Caribbean was often a death sentence for the enslaved. In 1756, a 26-year-old, mixed-race cooper named “Cuff, belonging to Capt. Daniel Marquand” fled a ship in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[11] Minors and Cuff had grown up together in the Brown and then the Marquand household.[12] He might also have been baptized.[13] Perhaps Norton’s fate lead Cuff to escape to Canada? The details of Minors’s life in Nevis and his relationship with Craddock are unknown, but he was sold again in 1757 to “Messrs. Bodkin and Farrall on the Island of St. Croix.”[14] Nearly twenty-five years after Denmark purchased the island from France, St. Croix was rapidly filling out with settlers and slaves. What were Minors’s impressions of plantation slavery? Who became his kinfolk? Was he afraid of dying on a sugar plantation?

Historians have created a term for Minors’s next bold move: “Maritime maronage.” On small Caribbean islands like Danish St. Croix, enslaved people did not have the advantage of large forests, mountain ranges, or swamps where they could hide for long periods of time. Most people who wanted to “go maroon” for months or escape slavery permanently had to flee to the sea.[15] Whether he stayed in town or on a rural plantation, Minors was never far from a port. On July 1, 1760, he hopped aboard the sloop Boscawen in St. Croix bound for Louisbourg, Nova Scotia.[16] Somewhere, probably Boston, he slipped off. His enslavers got word to William Kelly and Henry Lloyd, prominent merchants in New York City and Boston, about Minors’s escape. Over the next two years they placed at least 26 ads in newspapers from Pennsylvania to New Hampshire.[17] By 1762, Lloyd believed Minors had come back to Newbury, noting he had “been seen in and about (town) sundry Times since his Elopement.”[18] They raised the initial reward to $60, ten times the $6 average reward in Massachusetts newspapers around this time.[19] But Minors always stayed one step ahead of them. He might have seen the ads and used an alias to evade detection with help from free and enslaved people in the area. Was his mother Mariah, now in her 60s, still alive? What sorts of risks would a daring Minors take to try and see her and what was their possible reunion like?

Then in June 1762 the ads stopped. Bodkin and Farrall had seemingly given up. Minors’s next moves mixed patience with brashness and a talent for evasion. In March 1768, almost six years later, Norton entered a church in Canterbury, New Hampshire, 57 miles northwest of Newbury, to baptize a son “John” with “Mary,” apparently his wife.[20] Minors seemed to be moving throughout Massachusetts and New Hampshire, finding work and creating a family. Then, less than a year later in April 1769, two men, possibly slave catchers, captured Minors in Middlesex County and delivered him to the jail in Charlestown.[21] After nearly two months the Middlesex Sherriff was ordered to transfer Minors to Essex County. He wrote back two days later: “Since my receipt of this writ I have not had the body of Norton Miners (sic) in my custody.”[22] Minors had escaped again. Near capture did not dissuade Norton and Mary from returning to a church in Newburyport (Newbury’s new neighboring town[23]) in 1771 to baptize their second child, Timothy.

Norton probably lost his fugitive status between 1775 and 1783. During the fog of the Revolutionary War enslaved people, possibly hundreds, walked away from the homes of absent enslavers or were manumitted in wills.[24] Minors joined the Continental Army. He served almost 9 months between 1778-1779 near Boston’s North River and another month in 1780.[25] Between 1777 and 1786, he and Mary baptized five more boys – Stephen, Joseph, Leadington, James, and William – in Newbury.[26] By taking these steps, Mary and Norton showed a determined Christian faith, a shrewd understanding of Christianity’s liberatory potential in New England, or both.

When Minors died and where his body rests remain two final mysteries. On March 27, 1790, Samuel Marsh recorded his intent to marry Norton’s widow Mary “Minah” in a Newburyport church.[27] That year, the country’s new census takers identified Marsh as the head of a Newbury household with seven other free, “non-white” people.[28] Whether those seven people were Mary and six of her children with Norton cannot be confirmed.

View References

[1] The baptism date was April 21, 1728. Vital Records of Newbury, Massachusetts, to the End of the Year 1849, Vol. 1 (Salem, Mass.: Essex Institute, 1911), 564. https://archive.org/details/vitalrecordsofne01newb_0/page/n1131/mode/2up (accessed March 12, 2024). Queen Anne’s Chapel would later become part of what is today called St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. Queen Anne’s Chapel no longer exists. A special thank you to St. Paul’s church historian Bronson de Stadler who tracked down the original baptism records that show both Norton and Mariah baptized on the same day. The original records also include Mariah’s age.

[2] “In case of my death and my wife, I give my Negro Wench Maria & her Son their Freedom.” This clause was perhaps as part of an agreement related their Christian conversion. Brown made a separate direction to leave half of his “Negro slaves” to his wife Mary Brown. “Richard Brown, Will, September 16, 1730.” Essex County, Massachusetts, Probate Records and Indexes 1638-1916; Massachusetts. Court of Insolvency (Essex County); Probate Place: Essex, Massachusetts Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1635-1991 [database on-line] (Lehi, Utah, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015).

[3] There is conflicting information about Brown’s death date and his age at the time of his death. Brown died February 26, 1732/33 or 1734/35. Vital Records of Newbury, Massachusetts, to the End of the Year 1849, Vol. 2 (Salem, Mass.: Essex Institute, 1911), 555. https://archive.org/details/vitalrecordsofnew02newb/page/554/mode/2up?q=Brown (accessed March 18, 2024). This record indicates he was about 43 when he died. However, there are no baptisms of a Richard Brown in 1690 in the Newbury vital records. There is a Richard Brown born September 12, 1675, which would make Brown 56 or 58 at the time of his death. Vital Records of Newbury, Vol. 1, 71. https://archive.org/details/vitalrecordsofne01newb_0/page/n145/mode/2up (accessed March 17, 2024). Mary Brown was probably March 24, 1708, as Mary Hudson, Vital Records of Newbury, Vol. 1, 232. https://archive.org/details/vitalrecordsofne01newb_0/page/n467/mode/2up (accessed March 18, 2024). Separate records from Ancestry.com list a second possible birthdate as December 31, 1709. Mary Hudson married Richard Brown on June 19, 1726, which would mean she was 16 or 18 at the time of her marriage. Vital Records of Newbury, Vol. 2, 69. https://archive.org/details/vitalrecordsofnew02newb/page/68/mode/2up (accessed March 17, 2024). She died in 1785. Vital Records of Newburyport, Massachusetts, to the End of the Year 1849, Vol. 2 (Salem, Mass.: Essex Institute, 1911), 713. https://archive.org/details/vitalrecordsofne02esse/page/n717/mode/2up (accessed March 18, 2024).

[4] On May 12, 1740, his former wife Mary Brown ““alias Marquand” amended some debts “of her late husband Richard Brown.” Brown had recently remarried. Newbury town records for February 23, 1739/40, refer to a “Capt Daniel Marquand of Newbury,” who “informed…his intent of marriage with Mrs. Mary Brown of Newbury.”

[5] Two Hundredth Anniversary, St. Paul’s Parish, Newburyport, Mass. Commemorative Services with Historical Addresses (Newburyport, Mass., 1912), 40-41. https://archive.org/details/twohundredthanni00newbiala/page/40/mode/2up (accessed March 20, 2024).

[6] “These are to give Notice to all Persons whom it may concern, by Capt. Daniel Marquand, the late Commander of the Ship Experiment, That whoever has any Demands for Service done on Board said Ship on the late voyage to Jamaica, are hereby desired to make them of the said Marquand; or leave them in writing with Mr. Daniel Wentworth, merchant in Portsmouth, in New-Hampshire, before the Middle of February next.” Boston Post Boy, January 9, 1744.

[7] A surviving tax list dated around 1750 lists 44 enslaved people in Newbury. “Essex County tax list, circa 1750,” box 3, Hudson collection, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. New York, New York. Information obtained via email correspondence with NYPL librarian, March 15, 2024. Fifty enslaved people, 34 men and 16 women, are listed as living in “Newburyport,” in the 1754 Massachusetts Slave Census, Primary Research, https://primaryresearch.org/slave-census/?town=newbury&county=essex (accessed March 20, 2024). This information probably includes both Newbury and Newburyport. See footnote 20.

[8] Kelly and Lloyd’s ads were always generic about Minor’s physical description. He stood between 5’8” and 5’10.”

[9] Boston Evening-Post, March 29, 1762. Some of the early advertisements for Norton Minors claimed that his enslaver in “New England” was a “Mr. Mark Quane” who sold him to Craddock. The later advertisements named Daniel Marquand as the enslaver. I think it is unlikely Marquand sold Minors to Quane who then sold him to Craddock, although such a possibility exists. More likely, I think, is that the early ads named the incorrect enslaver. I have not found references to Mark Quane in Newbury vital records.

[10] Economic problems in 1760s Boston led New England enslavers to sell enslaved people. Marquand’s sale of Minors was probably before this downturn. Jared Ross Hardesty, “Disappearing from Abolitionism’s Heartland: The Legacy of Slavery and Emancipation in Boston,” International Review of Social History 65, (2020): 145-168.

[11] Cuff is described as a “Molatto Servant Man,” and a “good Cooper, aged about 26 years.” Boston Evening Post, July 26, 1756.

[12] Minors would have been about 33 in 1756. A 1735 probate inventory of the Brown household includes 8 “Negroes,” Thomas, Benneto, Cuffee, Norton, Cuffee “Jun.,” Mariah, Peach, and Frann. Norton is assigned a value of $80, the highest value among the 8 servants. Cuffee is assigned a value of $70 and Cuffee Jr. is assigned a value of $35. Given that “Cuff” is 26 in 1756 newspaper ad, he is probably “Cuffee Jr. in Norton’s probate inventory. “Richard Brown, Probate Inventory, April 8, 1735.” Essex County, Massachusetts, Probate Records and Indexes 1638-1916; Massachusetts. Court of Insolvency (Essex County); Probate Place: Essex, Massachusetts Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1635-1991 [database on-line] (Lehi, Utah, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015).

[13] On September 28, 1735, “Coffee” of “Madam Brown” was baptized in the same church as Norton. It is possible this is the adult “Cuffee” rather than young Cuffee Junior, in Brown’s probate inventory. Coffee’s baptism does not appear in the published vital records available online. Special thanks to Bronson de Stadler for providing information from the original church book.

[14] “Bodkin” and “Farrall” were almost certainly Laurence Bodkin and Mathias/Matthew Ferrall, part of an Atlantic network of Irish Catholic merchants who traded legally and illegally with Dutch, Danish, British, French, and Spanish colonies. Olga Power has written extensively about Bodkin, who owned warehouses in Christiansted, St. Croix’s largest city, and sugar plantations. He participated in the slave trade, shipped crops to multiple markets, including smuggling to Saint Domingue. Olga Power, “Irish planters, Atlantic merchants: the development of St. Croix, Danish West Indies, 1750-1766” (Ph.D. diss., University of Galway, 2011), esp. 121-123.

[15] N. A. T. Hall, “Maritime Maroons: ‘Grand Marronage’ from the Danish West Indies,” The William and Mary Quarterly 42, no. 4 (1985): 476-498.

[16] New-York Gazette, November 17, 1760.

[17] The 26 ads I have found are: New-York Mercury, November 10, 1760; New-York Gazette, November 10, 1760; Boston Post-Boy, November 17, 1760; New-York Gazette, November 17, 1760; New-York Mercury, November 17, 1760; New-York Mercury, November 24, 1760; Boston Post-Boy, November 24, 1760; Boston Post-Boy, December 1, 1760; New-York Gazette, December 1, 1760; Pennsylvania Journal, December 11, 1760; Pennsylvania Journal, January 22, 1761; Pennsylvania Journal, February 12, 1761; Pennsylvania Journal, February 19, 1761; Pennsylvania Journal, February 26, 1761; Boston Evening-Post, March 29, 1762; Boston Gazette, March 29, 1762; Boston Post-Boy, March 29, 1762; Boston News-Letter, April 1, 1762; Boston Gazette, April 5, 1762; Boston Post-Boy, April 5, 1762; Boston Evening-Post, April 12, 1762; Boston Post-Boy, April 12, 1762; Boston Evening-Post, April 26, 1762; Boston Evening-Post, May 3, 1762; New-Hampshire Gazette, May 28, 1762; New-Hampshire Gazette, June 4, 1762. The Freedom on the Move database lists an ad in Parker’s New York Gazette, November 20, 1760, without an image of the ad. I believe this is the same as the New York Gazette from November 17, 1760, since the paper did not publish an issue on November 20. The Freedom on the Move database also lists an ad in the Boston Gazette, November 16, 1761, also without an image. I could not locate this ad in the actual newspaper.

[18] Boston Gazette, March 29, 1762.

[19] The initial reward was $40. Average reward of $6.14 dollars calculated from sample of 51 ads in Massachusetts newspapers published between 1760-1765. Ads collected from Freedom on the Move database. Calculation includes 3 ads offering rewards in pounds. One ad indicated $20 = 6 pounds, which was used as an exchange rate. The sample excludes one ad of freedom seeker from Connecticut that offers reward in “York” money. The sample also excludes 7 ads which do not give specific reward amount but instead say a person will be “well” or “handsomely” rewarded. The largest award for a freedom seeker other than Minors was $20 for man named Boston. Boston Post Boy, June 28, 1762.

[20] The baptism took place on March 22, 1768. Vital Records of Newbury, Vol. 2, 322. https://archive.org/details/vitalrecordsofne01newb_0/page/n647/mode/2up (accessed March 16, 2024).

[21] The two men, “John Densmore” and “Alexander Gitriot” cited the New Hampshire Gazette ad from April 19, 1762. Suffolk County (Mass.) court files, 1629-1797, Court files v. 812 cases 131736-131825 1768-1769, Family Search (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSR4-DG3S?i=393) Images 394-399 of 805. (accessed March 18, 2024). Note: Family Search doesn’t provide a recommended citation for this source.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Newburyport, which was closer to the ocean, split off from Newbury to form a separate town in 1764. The Marquand house, where Minors had lived in his youth, was in Newburyport.

[24] Gloria Whiting, “Emancipation without the Courts or Constitution: The Case of Revolutionary Massachusetts,” Slavery & Abolition (2019): 1-21.

[25] “Massachusetts, Revolutionary War, Index Cards to Muster Rolls, 1775-1783,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSQZ-6WHT-F?cc=2548057&wc=QZZQ-MHC%3A1589088739 : 20 September 2019), Mills, Drake – Moffatt, Joseph > images 932 and 1009 of 2698; Massachusetts State Archives, Boston (accessed March 19, 2024).

[26] Vital Records of Newbury, Vol. 1, 322. https://archive.org/details/vitalrecordsofne01newb_0/page/n647/mode/2up (accessed March 12, 2024). I have an outstanding inquiry with archivists at the Presbyterian Historical Society, which holds the original baptism records for a specific Newbury church where Norton and Mary might have baptized their five sons. One of the unanswered questions is whether Minors baptized any of these sons at the same church that the Marquand family attended. Linking Minors and Daniel Marquand, who died in 1789, through a church after Minors returned from St. Croix would raise a series of questions about their possible contacts.

[27]Vital Records of Newbury, Vol. 2, 329. https://archive.org/details/vitalrecordsofnew02newb/page/328/mode/2up (accessed March 16, 2024).

[28] The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC; First Census of the United States, 1790.; Year: 1790; Census Place: Newbury, Essex, Massachusetts; Series: M637; Roll: 4; Page: 433; Family History Library Film: 0568144, Ancestry.com. 1790 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. (Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010). Original data: First Census of the United States, 1790 (NARA microfilm publication M637, 12 rolls), Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29 (National Archives, Washington, D.C.).