The simple woodcut images accompanying many runaway advertisements were striking, and to this day they capture the attention of readers scanning the pages of eighteenth-century newspapers. Each represented a dark-skinned person in motion, escaping from an enslaver who hoped that readers who noticed these images and read the accompanying advertisements might help recapture and return the enslaved people who had dared to seek freedom. The images reflect our understanding of freedom seekers as enslaved people who fled on land, traveling along roads, through woods and marshes, across streams and rivers, through plantations, farms and uncultivated land, always moving away from their enslaver to a destination where they hoped to secure freedom. But not all freedom seekers ran through the North American landscape. A great many males sought freedom on ships, hoping to escape across the waves. Escaping primarily from major seaboard cities like Charleston, Savannah, and Wilmington, the freedom seekers who were able to get away from these ports quite likely had a greater chance of achieving freedom than those who escaped these places on foot.[1]

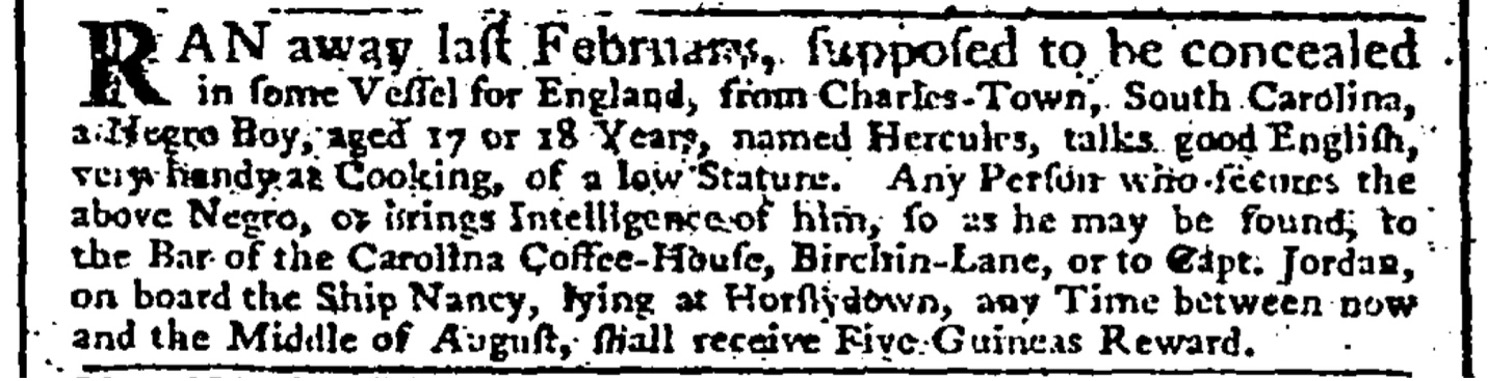

Was Hercules one of these maritime freedom seekers? If the information in a London newspaper advertisement was correct, Hercules had escaped slavery in South Carolina and traveled on a ship all the way to London. Hercules had absconded in February of 1766. No advertisements for him appear in surviving issues of South Carolina newspapers, and as far as we can tell, this single advertisement in a London newspaper is the only one. Apparently whoever paid for the London advertisement was sufficiently confident that Hercules was more likely to be in England than in South Carolina that he went to the trouble and expense of advertising for the freedom seeker in a London newspaper.[2]

The identity of Hercules’ enslaver is unclear. It may have been James Jordan, a South Carolinian who captained the Nancy, a ship that sailed between Charleston, the Caribbean, and the British Isles. Was the young man the enslaved sailor and personal attendant of Captain Jordan? It was fairly common for ship captains to use enslaved boys and young men as crew members and as servants. Or were Jordan and the manager of the Carolina Coffee House in London acting as agents for an enslaver back in Charleston?

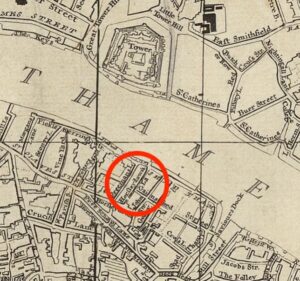

The Carolina Coffee House was in the heart of the financial district of the City of London. The Royal Exchange was close by, on the north side of Cornhill; the East Indian Company a few dozen yards to the east on Leadenhall Street; the Royal African Company further north on Throgmorton Street, and more coffee shops in the streets and alleys connecting these institutions. Ship captains, merchants, and investors connected to the South Carolina trade met in the Carolina Coffee House, and it was a logical place to seek information about ships recently arrived from Charleston, as well as the people aboard them. Anyone who had information about the whereabouts of Hercules, or who had captured him, could go to either the coffee house or directly to Captain Jordan aboard the Nancy. Jordan would not have been in London for long. The Nancy was moored off Horsleydown Steps, a rickety wooden stairway down to the river in Southwark, across the Thams from the Tower of London.

Hercules’ only appearance in surviving records appears to be this one advertisement, suggesting that he may have made a successful escape Charleston. The city contained a very small free Black population before the War for Independence, and the young man would not have found it easy to remain free within the small city: in 1770 there were fewer than 1,300 dwellings in Charleston. It was becoming a focal point for North American slavery and the slave trade; newspapers in the 1760s and 1770s were filled with advertisements offering for sale newly arrived enslaved Africans. Of the more than 300,000 enslaved Africans whose place of arrival in what would become the United States is known, almost half disembarked in Charleston. The presence of so many “Guineamen” or slave ships was all too apparent. In the later 1760s, residents complained that the bodies of so many dead Africans had been thrown off ships in Charleston’s harbor, that their decomposition in nearby marshes represented a threat to public health. The deaths of these poor souls bothered White people less than the smell. The brave few who tried to escape slavery in and around Charleston were trying to achieve freedom in an incredibly dangerous place. Little wonder that some, perhaps including Hercules, chose to try and gain passage on a ship that would get them far from the city.[3]

We know very little about Hercules. He was 17 or 18 years old, relatively short, spoke good English, and was a good cook. If he managed to secure passage on a ship bound for London, he likely worked as a sailor or perhaps a ship’s cook. If he had been enslaved by Jordan or another ship captain, he would have learned seafaring labor, and perhaps he was able to convince a different ship captain that he was a free man, and an experienced sailor. There were laws against captains taking on runaways but often ships that had come from Africa and the Caribbean had lost significant numbers of White crew men to tropical diseases. Anxious to get back to sea and desperate for new sailors, captains may have occasionally taken on young men whom they may have suspected were passing as free.

What must it have felt like for a young man like Hercules to see Charleston disappearing over the horizon, and to feel the freedom of an open sea and the wind in his face? And then, after weeks aboard a ship, how must London have appeared? Charleston was the richest city in British North America, but in 1770 it was home to fewer than 11,000 inhabitants. London was a massive city of some 750,000 people, tremendously cosmopolitan, and by this date home to the largest urban free Black population in Britain and its colonies. If Hercules made it to London, he had a good chance to maintain his freedom for a long time. He quite likely dropped the name given to him by an enslaver, and perhaps he appears in the baptismal or marriage records of a London church with a name of his choosing. Perhaps he continued to live and work as a free Black sailor, or he may have found work in London where there was a huge market for unskilled labor. If Hercules made it to England his had been one of the longest journeys from slavery to freedom.[4]

View References

[1] Marcus Rediker, Freedom Ship: The Uncharted History of Escaping Slavery by Sea (New York: Viking, 2025). Although focused on the antebellum era, Rediker’s book adds greatly to our understanding of maritime escape from slavery.

[2] No advertisements for Hercules appeared in surviving issues of The South Carolina and American General Gazette, the South Carolina Gazette, or The South Carolina Gazette; And Country Journal that were published in 1765 or 1766.

[3] Emma Hart, Building Charleston: Town and Society in the Eighteenth Century British Atlantic World (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010), 7, 101-2; Gregory E. O’Malley, “Slavery’s Converging Ground: Charleston’s Slave Trade and the Black Heart of the Lowcountry,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d. ser., 74, 2 (2017), 271-2.

[4] Hart, Building Charleston, 102; “Population in the Colonial and Continental Periods,” A Century of Population Growth in the United States, 1790-1900 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1909), 13; Simon Newman, “Freedom-seeking slaves in England and Scotland, 1700-1780,” English Historical Review, 134, 570 (October 2019), 1136-68.