On November 8th, 1775, an enslaved man named Titus seized his opportunity for freedom. He escaped from John Corlis’s farm in Shrewsbury, Monmouth County, New Jersey, just one day after Virginia’s Royal Governor, Lord Dunmore, issued a proclamation offering liberty to enslaved people willing to join the British cause. Dunmore declared that “all indentured Servants, Negroes, or others (appertaining to Rebels)” would be freed if they bore arms for the Crown.[1]

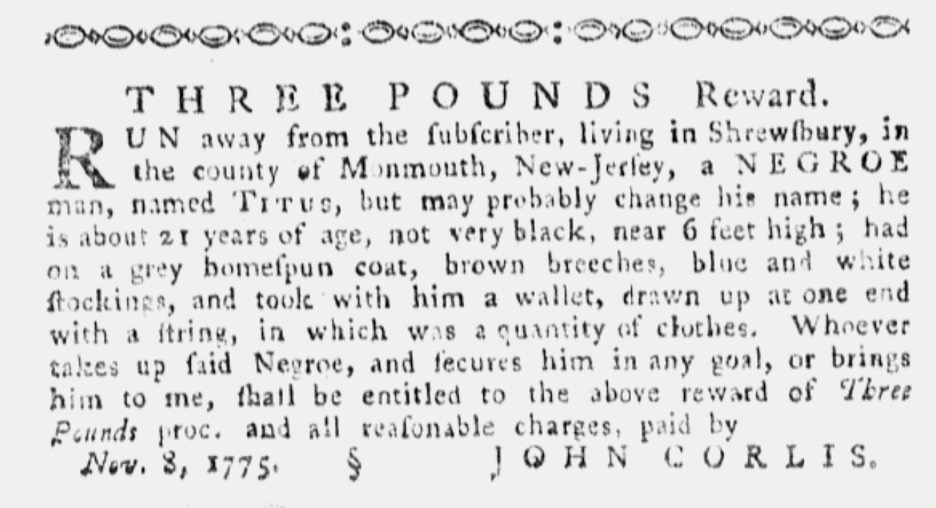

John Corlis’s runaway notice described Titus as about twenty-one years old, nearly six feet tall, and “not very black”, a detail that may suggest mixed ancestry. Corlis also warned that Titus “may probably change his name.”[2] Titus’s self-emancipation was not a mere flight from a cruel master, but also one of the earliest acts of the American Revolution’s freedom struggle. In this struggle, Titus not only obtained a new identity, but a new name that would reverberate through time: Colonel Tye.

Titus’s escape was among the earliest of a wave of self-emancipations across North America during the 1770s. The 1772 Somerset decision in England, which ruled that slavery lacked firm grounding in English law, was widely interpreted by enslaved people in the colonies as a hopeful signal. When war broke out in 1775, thousands of enslaved people fled to British lines seeking the freedom Patriot enslavers denied them.[3] Amid this growing wave of self-emancipation, Titus’s own situation was shaped by the man who enslaved him. Corlis was a Quaker, a community increasingly committed to manumission of all enslaved people, yet he refused to free Titus. News of Lord Dunmore’s impending proclamation was already circulating among enslaved communities, spreading through sailors, messengers, and informal communications networks. By late 1775, Titus may have concluded that Corlis had no intention of ever granting him liberty. With both the injustices he faced and the Crown’s promise of emancipation, Titus chose to “self-emancipate.”[4] Douglas Egerton even suggests there is reason to believe Titus “literally threw down his hoe” upon hearing Dunmore’s proclamation, leaving Corlis’s farm almost immediately.[5]

After slipping off the Corlis farm, Titus apparently made his way south toward the British lines, joining the 2,000 enslaved people who fled to Virginia to join Dunmore’s forces.[6] Changing his name to Tye, he enlisted in Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment, a British provincial corps of formerly enslaved Black volunteers fighting under the motto “Liberty to Slaves”. However, his transition into military life was not instantaneous. As Egerton notes, Tye “vanished from the sight of history” for nearly two years before reappearing around 1778 as a skilled guerrilla fighter.[7] The only surviving hint about these missing years is a brief contemporary remark that provides a vague association with Dunmore.[8]

Although the British army did not formally commission Black officers, they granted honorary titles to distinguish them.[9] Graham Hodges notes that the British tradition of giving informal or honorary military titles to Black soldiers originated among the forces stationed in the Caribbean.[10] This practice explains how Tye, although never formally commissioned, came to be widely known as “Colonel Tye” among Loyalists and fellow soldiers. Within a few years, stories of his exploits would spread through New Jersey and beyond, gaining respect from Loyalists, British officers and fellow Black soldiers.

Tye’s first recorded military actions occurred in June 1778 at the Battle of Monmouth in his home state of New Jersey, where he captured a Patriot militia captain and immediately gained a daunting reputation.[11] Leading a small band of Black and white Loyalists, he launched a series of raids throughout Monmouth County.[12] In July 1779, he led a strike on Shrewsbury, seizing livestock, supplies, and several Patriot prisoners, before retreating across the backroads he knew well.[13] His knowledge of the landscape allowed him to attack Patriot estates, disrupt supply lines, and earn substantial bounties from British commanders, who paid his men for successful missions in gold guineas.[14] By the winter of 1779-1780, Tye emerged as the leading figure of the Black Brigade, an elite guerrilla unit operating alongside the Queen’s Rangers to defend British-held New York and gather provisions.

Tye’s campaign reached its height in the summer of 1780. On June 9th he led a raid capturing Captain Barnes Smock and several members of the Monmouth County militia. Additional raids followed throughout June, during which Tye’s men plundered patriot homes. Throughout this period, the Black Brigade suffered almost no casualties while consistently undermining local Patriot authority.[15]

In September 1780, Colonel Tye took charge of his final raid. He and a mixed force of Black Brigade fighters and white Loyalists set out to capture Captain Joshua Huddy, a Patriot militia captain who had long harassed Loyalists.[16] On the morning of September 1, 1780, Tye’s raiders surrounded Huddy’s house in Colts Neck, New Jersey.[17] Huddy fended off Tye’s band for two hours with musket fire everywhere. Unable to take the house, the Loyalists set it on fire and forced Huddy to surrender. During this battle, Colonel Tye was shot in the wrist by a musket ball.[18] At first, the wound seemed minor, but within a few days, it became infected. Sepsis set in, which likely led to tetanus, or lockjaw, a dreaded complication in the eighteenth century.[19] Tye’s condition worsened rapidly, and muscle spasms immobilized the guerrilla leader. In September of 1780 this severe infection led to Colonel Tye’s death. He was about twenty-seven years old. Tye’s death dealt a heavy blow to the Black Brigade’s operations in New Jersey.[20] In the brief span between 1775 and 1780, Tye had transformed himself from an enslaved farm laborer into one of the most feared and highly effective Loyalist commanders. That someone once held in bondage could become a central figure in Monmouth County’s guerrilla conflict reveals the scale of Tye’s impact during these years. Leadership of the band passed to another Black Loyalist, Colonel Stephan Blucke, who continued raiding through 1781-82 in place of Colonel Tye. While Colonel Tye had been born into slavery, he had taken full advantage of the revolutionary moment to seize liberty, and he died a free man.

View References

[1] John Murray, “Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation (1775),” Encyclopedia Virginia, last modified May 15, 2023, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/lord-dunmores-proclamation-1775/ [accessed October 15, 2025].

[2] “Three Pounds Reward,” Pennsylvania Gazette, (Philadelphia), November 22, 1775.

[3] Douglas R. Egerton, Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 65.

[4] Alan Gilbert, Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 141–60.

[5] Edgerton, Death or Liberty, 66.

[6] Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 30.

[7] Egerton, Death or Liberty, 67.

[8] This was a reference to “brave Negro Tye, (one of Lord Dunmore’s crew,” in “Extract of a Letter from Monmouth, New Jersey,” Pennsylvania Packet, (Philadelphia), October 3, 1780.

[9] Douglas R. Egerton, Death or Liberty: 67–72.

[10] Bill Smith, “Teaching Colonel Tye: Slavery, Self-Emancipation, and the Black Brigade,” NJCSS Journal, March 27, 2023, TeachingSocialStudies.org, https://teachingsocialstudies.org/2023/03/27/teaching-colonel-tye-slavery-sel-emancipation-and-the-black-brigade/ [accessed December 15, 2025].

[11] Gilbert, Black Patriots and Loyalists, 141–160.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Joseph E. Wroblewski, “Colonel Tye: Leader of Loyalist Raiders—and Runaway Slave,” Journal of the American Revolution, February 17, 2021, https://allthingsliberty.com/2021/02/colonel-tye-leader-of-loyalist-raiders-and-runaway-slave/ [accessed December 15, 2025].

[14] Egerton, Death or Liberty, 69.

[15] Monmouth County Historical Association, “Colonel Tye and the Black Brigade,” https://www.monmouthhistory.org/250/colonel-tye-and-the-black-brigade [accessed December 3, 2025].

[16] Egerton, Death or Liberty, 67–72.

[17] Wroblewski, “Colonel Tye

[18] Ibid.

[19] Gilbert, Black Patriots and Loyalists, 141–160.

[20] Egerton, Death or Liberty, 67–72.