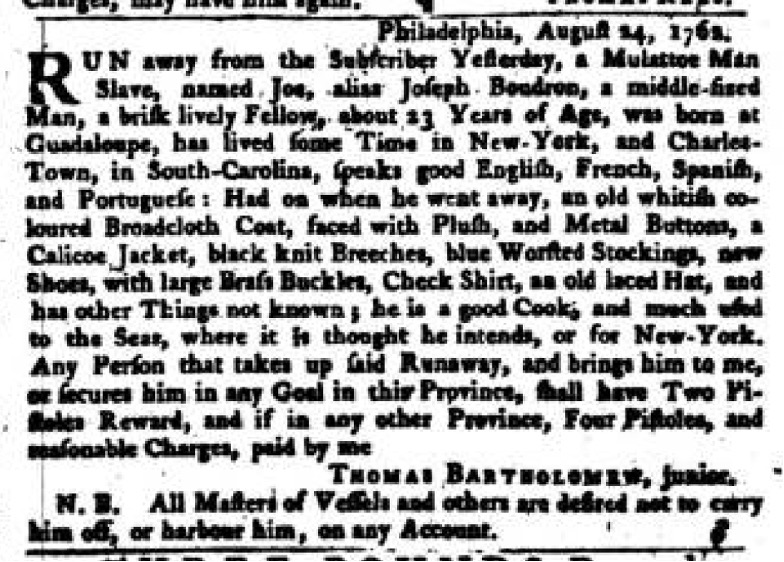

On August 24th, 1762, Joe decided to take his chance for freedom. Escaping from the Arch Street home of his enslaver, Thomas Bartholomew, Joe made his way through the streets of Philadelphia.[1] According to Bartholomew, Joe was twenty-three years old at the time of his escape and was proficient in four languages, French, English, Spanish and Portuguese. Bartholomew described Joe as a mixed-race, middle-sized man from Guadeloupe, who was skilled in cooking and had experience as a sailor. Bartholomew also mentions that Joe had lived in Charleston, South Carolina and in New York City. Joe’s life was one of mobility and adaptability, having traversed large sections of the Atlantic coast.

Born in the French colony of Guadaeloupe in 1739, Joe was quite likely raised to speak French. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, Guadalupe’s population of eleven thousand was fifty-eight percent enslaved; by 1720 it had more than doubled to twenty-four thousand with seventy-percent of them enslaved. By 1751, the nearly 41,000 enslaved people on the island constituted an overwhelming Black majority, representing over eighty percent of the island’s population.[2] European men frequently formed unions with Native or African women, and this likely explains Joe’s mixed-race background.[3]

According to Bartholomew, Joe used the full name Joseph Boudron. Boudron was undoubtedly a French last name. While his name marked him as coming from a French colony, Joe was a highly adaptable person. His knowledge of Spanish and Portuguese was possibly acquired during his time at sea, as he encountered traders and sailors across the Caribbean. His ability to cook would have made him particularly sought after aboard ships, where enslaved workers were often employed in this capacity.

When Joe eventually arrived in Charleston, he would have encountered a mix of phenomena familiar to the Caribbean. At the time, Charleston, South Carolina was British North America’s leading port for the slave trade, importing an estimated 93,000 enslaved people between 1706 and1775.[4] Exactly when Joe was in Charleston is unknown, but while there he would have been one member of a significant Black population. It is further possible that Joe lived in the French Quarter of Charleston, located towards the east end of the city along the city harbor. Perhaps ironically it was fellow French-speakers who helped him adapt to the lifeways and language of an English colony.[5]

Though there is no definitive proof of how and when Joe left South Carolina, one strong possibility is that he did so aboard the brig Hannah. The ship’s captain, Captain Noarth, worked frequently with Joe’s pursuer, Thomas Bartholomew, to transport goods and people between Charleston and Philadelphia.[6] In March 1761 Bartholomew posted an advertisement reading: “Just imported from Charles-Town, South Carolina, in the Brig Hannah, Captain Noarth, A Parcel of likely young Negros…”[7] This was the last known visit Captain Noarth made to Philadelphia before Joe’s escape.

Joe’s life in Pennsylvania would have been similar to his time in New York but entirely distinct from what he experienced in Charleston or the West Indies. The Black population in the North, especially in Pennsylvania, was drastically smaller. Pennsylvania’s slave trade did not begin to expand until 1729 and never reached the heights of Charleston or the West Indies. In 1762, the year Joe made his escape, traffic of enslaved people into Philadelphia peaked with the import of 500 people.[8] Joe would have had to adapt to a predominately white society and accommodate himself to life in the urban North. It is likely that Joe was one of a small number, if not the only enslaved Black person, who lived with and worked for Thomas Bartholomew.[9] In terms of Joe’s work, he either would have helped with Bartholomew’s business, or worked domestically, as was common within urban settings.[10] This may explain where Joe learned to cook, a profitable skill he could use after his escape. It is therefore possible that his adaptation to enslavement in the urban north may have provided Joe with additional tools and opportunities necessary on his journey to freedom.

Bartholomew suspected that Joe was bound for New York. While no definite record has been found of Joe’s next destination, there is evidence of a Black, mariner named Joseph who found his way aboard a French privateering ship that was cruising the North Atlantic coast around the time Joe (Joseph Bourdon) escaped.[11] A ship called the Prosperous Polly was sailing from Martinique to Providence, Rhode Island when it was captured by these French privateers. They attempted to sail the Polly to St. Croix, but the ship was quickly retaken by British privateers and taken to the Court of Vice Admiralty for the city of New York as a prize. In court it was revealed that “Joseph, the Negro” as trial records labeled him, had “come aboard the Polly along with the French prize crew.”[12] While Joseph himself did not speak, both French and English sailors testified he was a free man. One French sailor explained Joseph had entrusted him with a written instrument that “contained certain Proofs of his Freedom, which should they happen to be taken by the English might be of service to him in his Captivity, and might deliver him from Slavery.”[13] This document was unfortunately left aboard the French privateer. Trial records further describe Joseph as a “Spanish Negro” native to Puerto Rico.[14] While the details do not match what we know about Joe, they may have been a strategic claims to avoid connection to Bartholomew.[15] Fluency in Spanish and French would have made it possible for Joe to construct this alibi. The hearing resulted in a declaration that Joseph was a free man. If this was Joseph Boudron, gaining freedom only eighteen days after escape shows remarkable resourcefulness. Even if this was another man, we can see the possibilities open to Joseph Boudron had he been able to get to New York City, where passing as a free man—perhaps woith forged papers—he could join the crew of a ship.

Beyond this, Joe’s whereabouts become unclear. It is possible that Joe participated in the Revolutionary War on the side of the French. There is record of a French sailor named Joseph Bourdon who died on July 22nd, 1781.[16] If this was the man who had escaped from Bartholomew he would have been only forty-two when he passed away. He would have spent nineteen of those years living free. If Joe had indeed reinvented himself once more, this time as a French fighter, it would have been one more example of a life spent adapting to the turmoil of the Atlantic world. He was born into the violent horror of slavery in the West Indies, survived enslavement in both the colonial South and North, and ultimately escaped his enslaver at twenty-three years of age. While Joe undoubtedly deserved more than nineteen years of freedom, his achievement in navigating slavery and seizing freedom is a significant one. The potential traces of Joe that appear across the archival record reveal a compelling example of the consistent determination among the enslaved to pursue freedom.

View References

[1] Anna Coxe Toogood, Historic Resource Study, Independence Mall the 18th Century Development Block, Three Arch to Race, Fifth to Sixth Streets (Cultural Resources Management Independence National Historical Park, 2004) [accessed: December 28, 2025] https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/DownloadFile/465945 16.

[2] Laurent Dubois, A Colony of Citizens: Revolution and Slave Emancipation in the French Caribbean, 1787-1804 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004) 35.

[3] Adélaïde Marine-Gougeon, “The European Settling in the French Caribbean (Antilles – Guyana),” Bibliothèque Nationale De France [accessed December 30, 2025] https://heritage.bnf.fr/france-ameriques/en/european-settling-french-caribbean-antilles-guyana.

[4] Kenneth Morgan, “Slave Sales in Colonial Charleston.” The English Historical Review 113, no. 453 (1998): 905–27.

[5]Tim Fillmon, “Slave Auctions Historical Marker,” The Historical Marker Database [accessed December 30, 2025] https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=176650.

[6] “Advertisement.” Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), October 1, 1761.

[7] “Just imported…” Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), March 12, 1761.

[8] Gary Nash, Forging Freedom: the Formation of Philadelphia’s Black Community, 1720-1840 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988) 9.

[9] Nash, Forging Freedom, 11.

[10] Nash, Forging Freedom, 11.

[11] Charles Merrill Hough, ed., Reports of Cases in the Vice Admiralty of the Province of New York and in the Court of Admiralty of the State of New York 1715-1788 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1925) 199, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015057235080.

[12] Ibid., 199.

[13] Ibid., 199.

[14] Ibid., 200.

[15] For more on the ways enslaved peoples strategically shifted their identities, see James Sweet, “Mistaken Identities? Olaudah Equiano, Domingos Alvares, and the Methodological Challenges of Studying the African Diaspora,” The American Historical Review 114, no. 2 (2009): 279–306.

[16] Entry for Joseph Boudron, “États Unis, Combattants français dans la guerre révolutionnaire, 1778-1783,” Database, FamilySearch [accessed December 30, 2025] https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QP24-NPWM.