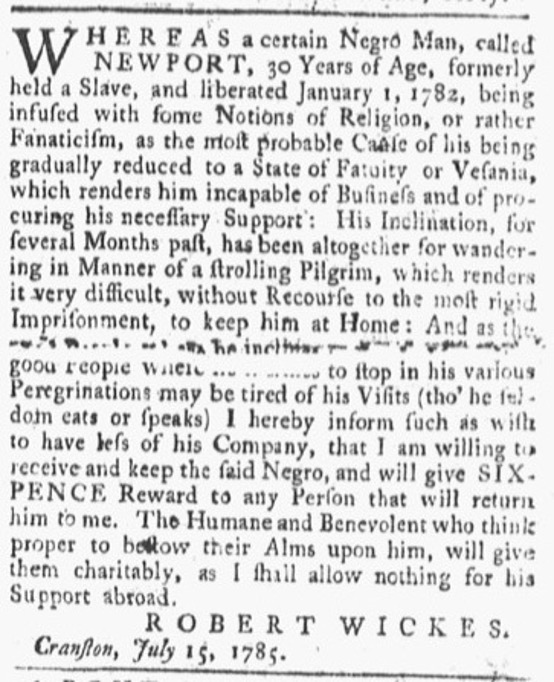

The advertisement that Robert Wickes placed in July 1785 was an unusual one. Thirty-year-old Newport was no longer enslaved, having been freed three years earlier. If we are to believe this notice, Wickes sought not to recapture Newport and extract labor from him, but instead sought to recover and care for a dependent who was unable to look after himself. In fact, Newport may well have created an independent life for himself after his emancipation, and may not even have been enslaved by Wickes: it seems that Wickes had brought Newport into his household as an act of charity.

Wickes was a forty-year-old doctor in Cranston, Rhode Island. The Wickes family had been in Rhode Island for more than a century, with many family members living in Warwick. In 1774, the Rhode Island census had recorded Dr. Wickes as still living in Warwick, in a large household of fourteen people, including seven “Black” people, most likely enslaved.[1] Wickes suffered from “a feeble and infirm constitution,” yet he appeared to have been committed to “being Useful to Mankind, in the Line if his Profession.” He died young, at the age of about 40 or 41, and his obituary recorded that Wickes “justly merited the Approbation of those who employed him, and deservedly established an eminent Character in the medical World.” Having “held true Religion in the highest Veneration and Esteem,” Wickes was laid to rest in the Quaker burial ground in Cranston.[2]

The advertisement placed by Wickes tells us little about Newport’s physical characteristics other than his gender and age. Instead, much of the text concerned Newport’s mental state, and his religiosity. According to Wickes, Newport had been “infused with some notions of Religion, or rather Fanaticism,” and that this had resulted in Newport “being gradually reduced to a State of Fatuity or Vesania.” Wickes was a deeply religious man, but as a medical professional he judged Newport to be mentally deranged and in a state of silliness or stupidity.[3] This had rendered Newport incapable “of Business and of procuring his necessary Support,” and he had begun wandering around the area “in Manner of a strolling Pilgrim.” Newport did not preach, and Wickes reported that the itinerant religious man simply went to other households, where some people offered him shelter and support. In the manner of advertisements for dependents from wives to apprentices who had eloped, Wickes made clear that he would not be responsible for any debts incurred by Newport, and the doctor offered a token reward of sixpence for his return.

What are we to make of this unusual advertisement? Given that Newport was a free man, and apparently not a contracted servant of Wickes, the doctor had no legal authority over the younger man. As best we can tell, Wickes’ concern for Newport was genuine, and he believed that the wandering pilgrim was unable to care for himself. But just because Newport’s “notions of Religion, or rather Fanaticism” may have appeared alien and irrational to Wickes does not mean that we should accept this assessment at face value. In slavery and in freedom African Americans were developing their own understanding and forms of Christianity, sometimes infused with elements of African spirituality. What Daina Berry has compellingly described as the “soul values” of Black folk found expression in language, song, folktales, and religious conversion, as well as in myriad secular forms.[4]

Wickes’ brief and dismissive description of Newport’s religiosity give us too little information to allow us to evaluate his faith. Just like many enslaved people, the depth and nature of his religiosity is hidden more than it is revealed by the surviving words of White folk. Quite possibly Newport really did suffer from psychological and mental problems, but that does not mean that his religious beliefs and faith were any less genuine, just that his mental health affected how he acted upon them. All we can do is speculate about Newport’s faith, and the apparently gentle, quiet, and pilgrim-like qualities that it brought out in him. A sermon, a premonition, a visitation from an ancestor or from God or his emissaries, any of these or other experiences may have affected Newport deeply, profoundly changing his understanding of himself and his place in the world. Perhaps what Wickes interpreted as the onset of “Fanaticism” was in fact a conversion experience, through which Newport shifted from a secular to a religious sensibility. Maybe Newport had left Wickes’ household and begun his wandering because, like some other African Americans, he had found God in the natural world. Daina Berry suggests that we must pay close attention to the testimony of enslaved people to learn more about their spirituality, but in the absence of more information we cannot know what exactly Newport had experienced and believed.

If we cannot know more about Newport himself, this brief advertisement does highlight the significance of faith and spirituality for many enslaved or formerly enslaved people. Often White Americans sought to utilize Christianity in order to keep the enslaved subordinate, but the souls of Black Americans were spiritual free soil. For some, at least, religious beliefs and actions helped them navigate life at least partly on their own terms, according to values and with objectives that were all their own.

Never a well man, Dr. Robert Wickes died a year later in1786. By then Newport was back in the Wickes household, perhaps of his own volition or maybe because he had been returned there by others. An inventory of Wickes’ estate included “2 negroes, Newport and Cloe, together with their wearing apparel.” Chloe’s legal status is unclear, but we know that Newport had been freed from slavery four years earlier. The assessors of Wickes’ estate may have assumed that both Newport and Cloe had been enslaved or were bound servants, but they neglected to place a value on either person “as [they] conceive[d] them to be an encumbrance.”[5] We know nothing of Newport’s life thereafter. The federal census of 1790 recorded that one free person resided in the Household of Sylvester Weeks in Cranston, while both enslaved and free people lived in the homes of Barney Weeks, Harry Weeks, and Thomas Weeks in Warwick.[6] If he was still alive, and in Rhode Island, perhaps one of these was Newport. Or maybe he had left again, “in the Manner of a strolling Pilgrim.” All that we have to try and understand Newport is a short reference to him in a single advertisement, characterizing him as mentally unstable and unable to properly care for himself, yet also highlighting his spiritual identity and its overriding significance to him.

View References

[1] Entry for Robert Wickes, Warwick, Rhode Island in Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and providence Plantations, Taken By Order of the General Assembly, In The Year 1774, arranged by John Bartlett, (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), 67.

[2]Untitled obituary for Dr. Robert Wickes, The Providence Gazette and Country Journal (Providence), August 26, 1786.

[3] The Oxford English Dictionary defines vesania as mental derangement, and fatuity as folly, sillness, and stupidity. See Oxford English Dictionary, https://www.oed.com [accessed December 5, 2024].

[4] Daina Ramey Berry, “Soul Values and American Slavery,” Slavery and Abolition, 42 (2021), 201-18.

[5] Wickes died “at Cranston, in [his] 41st year, Aug.19, 1786.” See James Newell Arnold, Rhode Island Vital Extracts, 1636-1850: Vol. 14, Newspapers, Marriages, Deaths (Providence: Narragansett Historical Publishing Company, 1891–1912. 420. The inventory of Wickes’ estate is quoted in Gladys W. Brayton, Other Ways and Other Days (Cranston, RI: Globe Publishing Company, 1975), 116.

[6] Heads of Families At the First Census of the United States in the Year 1790. Rhode Island (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 26, 15.