Surely all enslaved people believed in their hearts that they should be free. What is a little more surprising is the fact that a small number of the enslaved believed that the laws and court decisions of White society meant that they had in fact been born free rather than enslaved. Some took legal action to try and secure freedom, and if that failed they escaped, attempting to seize the freedom that rightfully was their’s. Stephen Butler was just such a man.

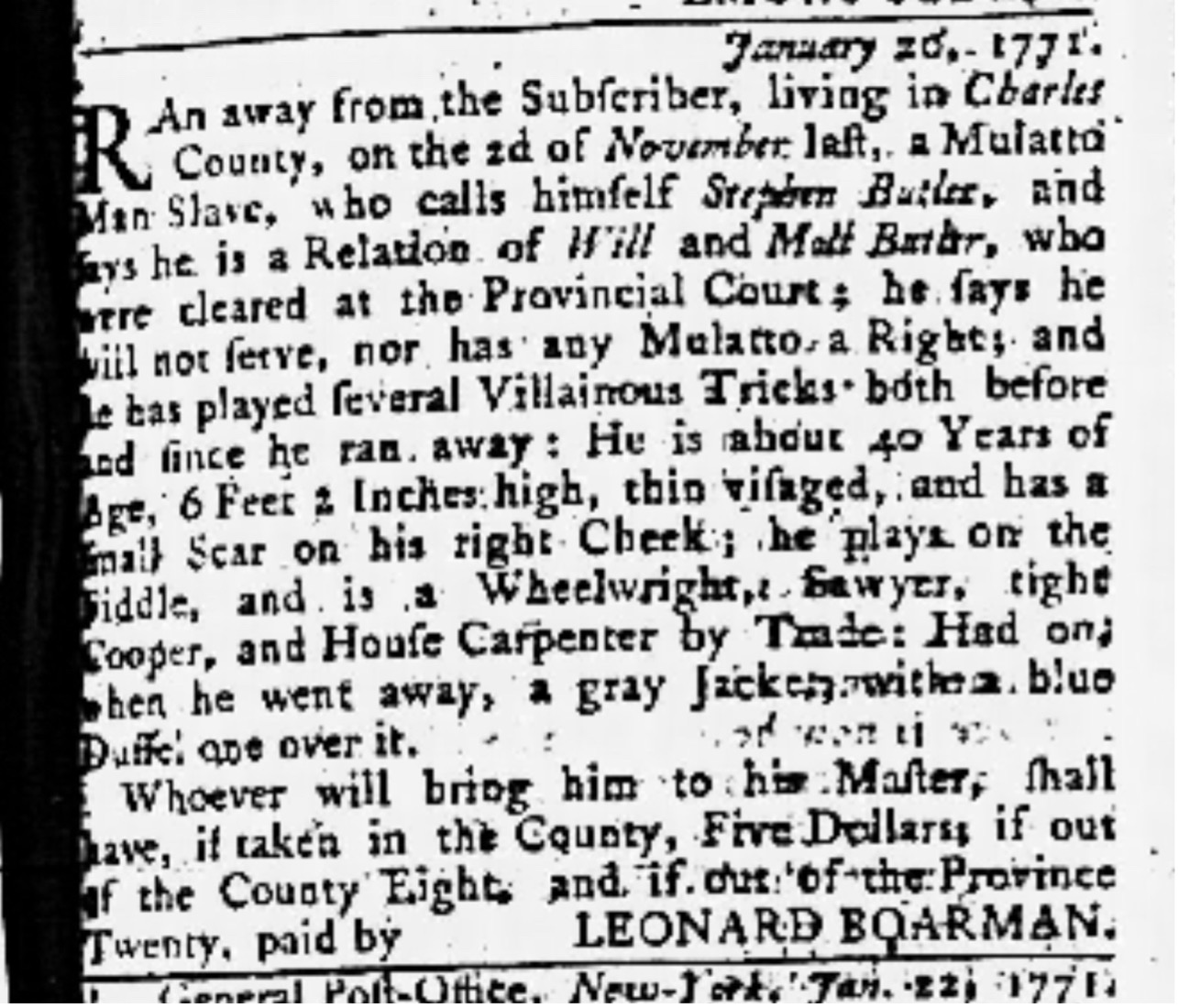

An earlier advertisement for Stephen Butler noted that he “says he is a Relation of Will and Moll Butler, who were cleared at the Provincial Court; he says he will not serve.”[1]

Stephen Butler was a descendant of Nell Butler and Charles, who in 1681 had been married by a Catholic priest on the Charles County, Maryland plantation of William Boarman. What made the union unusual was that Charles was an enslaved African owned by Boarman, while Nell Butler was an Irish indentured servant, a free woman whose labor had been purchased from Lord Baltimore by Boarman. In the seventeenth century Chesapeake indentured White men and women for a while outnumbered enslaved Africans, and these White people worked on plantations. While their legal status differed, for a brief period the work they undertook did not.[2]

A 1664 Maryland law specified that when a freeborn woman married an enslaved man, she would become a slave during her husband’s lifetime, and their children and descendants would be enslaved. A new 1681 law repealed the 1664 act, and it specified that White women who married enslaved women would remain free, as would their children. Nell and Charles married while the earlier law was in effect, but their children were born after the new law came in, raising questions over the status of the couple’s descendants. In 1770 William and Mary Butler, grandchildren of Nell and Charles, sued for their freedom. The Provincial Court ruled that William and Mary were free, but this was reversed by an appeals court. In 1792, however, the Appeals Court finally granted Mary Butler her freedom, and in the years that followed more members of the clan secured their freedom in this fashion.[3]

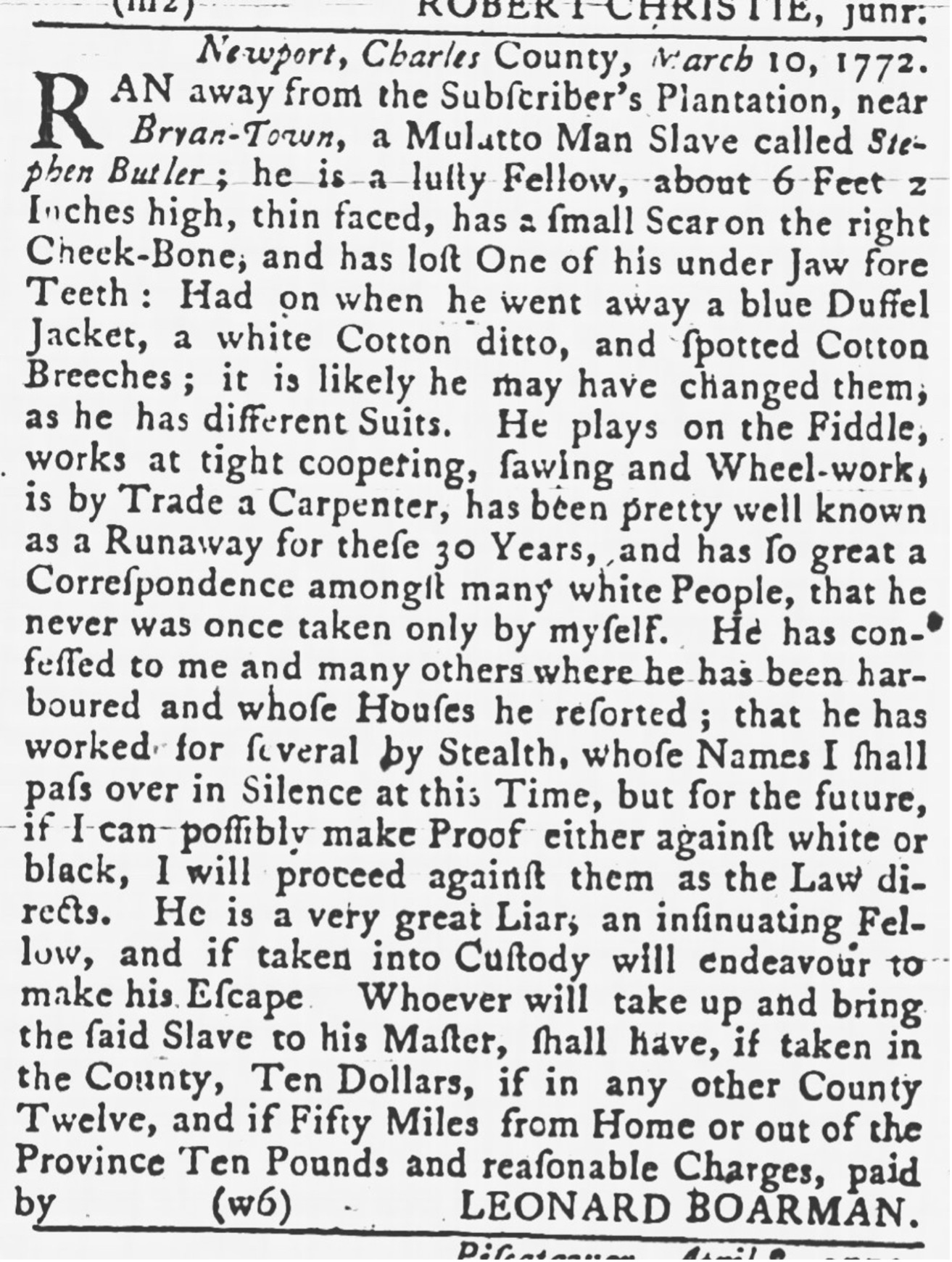

Leonard Boarman and the other planters who enslaved descendants of Nell and Charles resisted these freedom suits. In the first of the advertisements Boarman placed seeking Stephen Butler, the planter reported that the freedom seeker “calls himself Stephen Butler,” a blatant effort to de-legitimate the link between Butler and his free ancestors. Butler was a great-grandchild of the couple, and while thirty-four members of his generation were eventually able to achieve freedom, he was one of the sixteen who remained enslaved. How must this have felt, knowing that he and his family members had a legal right to freedom, yet being denied what many of his siblings and cousins secured? The advertisements written by Leonard Boarman described Stephen Butler as “a very great Liar, an insinuating Fellow,” who if recaptured “will endeavour to make his Escape.” Furthermore, Boarman reported, Butler “has played several Villanous Tricks both before and since he ran away.”[4]

We know nothing of these “villainous tricks,” but we can imagine the reality of Stephen Butler beyond Boarman’s negative construction of him. Butler was a strong, able, and proud man who felt legally entitled to freedom. Indeed, Boarman admitted that Butler was a skilled and able carpenter who could make barrels and hogsheads for tobacco and wheels for wagons. While Boarman was determined to deny Butler his freedom, it appears that other White Marylanders were less certain that this man should be enslaved. Butler was “well known as a Runaway for these 30 Years,” and he enjoyed “so great a Correspondence amongst many white People” that he was never taken up or recaptured by anyone other than Boarman himself. “Correspondence” is an intriguing term, and it suggests that when he escaped Butler was able to continue to interact with White Marylanders who knew him. Rather than hiding from White people who might know and recapture him, Butler appears to have held his head high and walked and worked amongst them. Boarman confirms this, stating that Butler had “confessed to me and many others where he has been harboured and whose houses he resorted [to].” It is more striking that at least some Charles County residents felt comfortable in helping Butler descendants remain at liberty when they escaped. Boarman complained in one advertisement that after escaping Butler “has worked for several [White people] by Stealth, whose Names I shall pass over in Silence at this Time.” It was very unusual for an advertisement for an escaped enslaved person to highlight the existence of White people who knowingly aided and abetted escapees. But for all that Boarman was angered by and threatened those White people who had employed Stephen Butler, it seems clear that among the White people who were otherwise committed to the institution of slavery, there were at least a few who were inclined to accept the self-liberation of a man who they believed had a right to freedom.[5]

Despite the fact that there was a degree of community acceptance that Stephen Butler and his relatives should be free, and a willingness to employ and harbor him when he escaped and sought work while passing as a free man, it appears that he was recaptured and eventually died in slavery. Three members of the generation that followed, each named Stephen Butler, secured their freedom in 1791, 1792, and 1793, but the Stephen Butler enslaved by Leonard Boarman was not so lucky. The 1794 inventory of Boarman’s property included a list of nine enslaved people, the oldest being Stephen, by then fifty-seven years old.[6]

None of Stephen Butler’s words remain, and his fiddle, his clothing, and the many products of his carpentry skill are all long gone. But even in the advertisements penned by his enslaver, we can see a little of Butler as a skilled professional man who believed that he was and of right should be free. As a younger man he had escaped regularly, and he was able to secure work passing as a free man, often working for White people who knew him. Perhaps when he played his fiddle Stephen Butler performed traditional Irish folk tunes, passed down from his great grandmother Nell. If he could inherit musical culture, why couldn’t he inherit freedom? It seems likely that Stephen Butler lived his whole life knowing that not just natural law but even the law of his enslavers should acknowledge his freedom.

View References

[1] “Ran away… Stephen Butler,” Maryland Gazette (Annapolis) February 14, 1771.

[2] For a fascinating analysis of Nell, Charles, and their descendants see chapter 2, “Marriage: Nell Butler and Charles,” in Martha Hodes, White Women, Black Men: Illicit Sex in the 19th-Century South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 19-38. For White servants in later-seventeenth-century Maryland see Lois Green Carr and Lorena S. Walsh, “The Planter’s Wife: The Experience of White Women in Seventeenth-Century Maryland,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 34 (1977), 542-71; Allan Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 45-77; Russell Menard, “From Servants to Slaves: The Transformation of the Chesapeake Labor System,” in Jeremy Black, ed., The Atlantic Slave Trade: Volime II, Seventeenth Century (London: Routledge, 2006), 355-90.

[3] For a family tree detailing the descendants of Nell and Charles, including those who secured freedom, see “Bloodlines to Freedom,” Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture, https://www.lewismuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Butler-Family-Tree5.pdf [accessed January 20, 2026]. See Ross M. Kimmel, Blacks Before the Law in Colonial Maryland (Master’s Thesis, University of Maryland, 1974), especially Chapter IV, “Freedom or Bondage—The Judicial Record,” https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/speccol/sc5300/sc5348/html/chap4.html [accessed January 20, 2026]; Hodes, White Women, Black Men, 19-38.

[4] “Ran away… Stephen Butler,” Maryland Gazette (Annapolis) February 14, 1771; “RAN away… Stephen Butler,’ Maryland Gazette (Annapolis) May 14, 1772.

[5] RAN away… Stephen Butler,’ Maryland Gazette (Annapolis) May 14, 1772.

[6] Leonard Boarman, Inventory, February 5, 1794, in “1791-1797 Charles County Maryland Inventories,” Michael R. Marshall, Charles County, Maryland, Wills 1791-1801. Liber AK-11(Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017), 218; “Bloodlines to Freedom,” Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture, https://www.lewismuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Butler-Family-Tree5.pdf [accessed January 20, 2026]. For the successful freedom suits of one of the men named Stephen Butler from the next generation, see “Stephen Butler v. Charles Carroll. Judgement Record. October 1791,” https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.mdcase.0014.076 [accessed January 20, 2026].