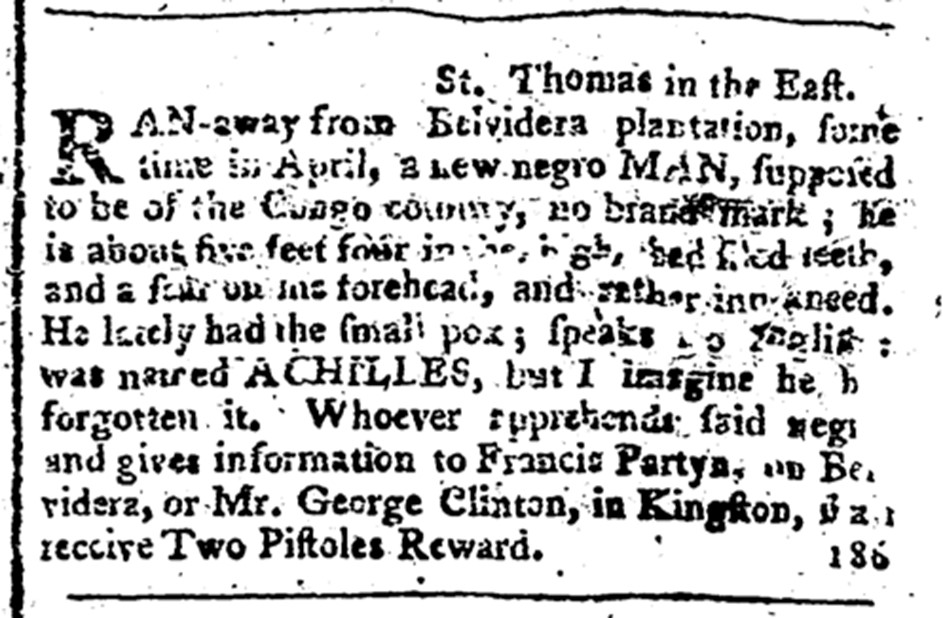

By July 4th 1776 Achilles had already freed himself. He had eloped in April, not long after arriving in Jamaica from West Africa. Francis Partyn, presumably the man running the Belvidere Plantation, believed that the freedom-seeker has come from “the Congo country,” the West Central African point of departure for just under half of all enslaved people transported across the Atlantic. Perhaps Achilles had been one of the 287 enslaved West Central Africans who in 1775 arrived in Jamaica on the slave ship Liberty from Liverpool, or one of 197 survivors of the Middle Passage who arrived aboard the Bristol slave ship Jason: both of these ships had brought their human cargos from West Central Africa to Jamaica in 1775.[1]

Perhaps surprisingly this man had not been branded, and his filed teeth and the fact that he spoke no English betrayed that he was “a new Negro MAN” recently arrived from Africa. The scar on his forehead may also have been a ‘country mark,’ evidence of ritual scarification undergone in his African home. Patryn, or another White person, had named the newcomer Achilles, but he had been at Belvidere Plantation for such a short time that Patryn “imagine[d] he had forgotten” the name imposed on him. But to the man who sought his freedom Achilles was not his name, and he surely held the name given to him at birth close, perhaps sharing it with other enslaved people during the Middle Passage voyage or in Jamaica, but a name that was unknown to his enslaver.

Belvidere was a large sugar plantation in St Thomas in the East at the eastern end of the island. It was owned by the absentee John Cope Freeman and a generation later was being worked by as many as 369 enslaved people: little wonder that Cope Freeman was a wealthy man. But the man we know only as Achilles wanted no part of this. No doubt traumatized by his Middle Passage voyage and determined to escape from the scenes of harsh labor and punishment at Belvidere, he escaped soon after arriving. Few newspapers survive from this period in Jamaican history and we cannot know whether more advertisements were placed for this man, or whether or not his attempt to free himself succeeded. The Blue Mountains lay about twenty miles north-west of Belvidere, and the Maroon community of Nanny Town lay even closer. These were not reliable sanctuaries, but whether or not Achilles found refuge there or perhaps with other enslaved people from his West Central African homeland, it was clearly possible for even newly arrived Africans to remain at liberty for extended periods. Between 1700 and 1775 more than 600,000 enslaved Africans arrived in Jamaica, many of them from West Central Africa, and it is far from inconceivable that the enslaved from a particular region offered aid or concealment to those of their countrymen who dared to escape. But when Partyn published this advertisement some six months after the man he knew as Achilles had escaped, the African continued to evade recapture.[2] We see very little of the man who refused to answer to the name Achilles. In the words of this advertisement, other than the most important fact of all. In the middle of 1776, the year of revolution and freedom, he too was determined to be free.

View References

[1] Liberty, Voyage 91787; Jason, Voyage 17857, Slave Voyages: Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, https://www.slavevoyages.org/voyage/database (accessed 1 July 2021).

[2] Will of John Cope Freeman of Abbots Langley Hertfordshire, 17 January 1788, The National Archives, PROB 11/1161/176.