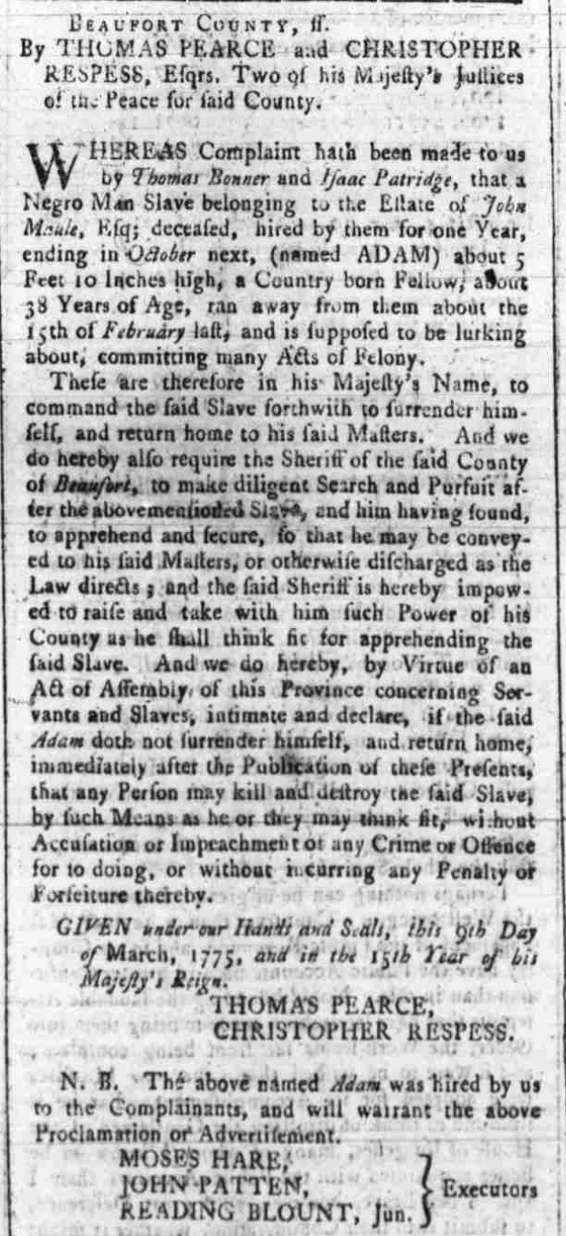

Sometime around the 15th of February 1775, an enslaved man named Adam fled from the northeastern coast of North Carolina. According to the advertisement placed in the North Carolina Gazette a month later, Adam was 5 foot 10 inches and 38 years old. Adam was older than many Freedom Seekers. Younger men were more likely to attempt escape as they were less likely to have extended familial ties, with children and spouses.[1]The advertisement also described Adam as “country born,” indicating that Adam was born somewhere in the American colonies rather than being a more recently arrived African-born victim of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Thus, Adam had likely spoken English all of his life, and knew the society he inhabited well. Some of Adam’s unusual story can be gleaned from surviving historical documents, but much needs to be imagined. By using our knowledge of law and social practice in late-eighteenth century North Carolina, and the content and significance of the extremely unusual advertisement seeking Adam’s surrender, capture, or murder, some sense of his story comes to life.

Prior to his escape Adam had lived on a large plantation in Beaufort County, North Carolina, at the mouth of the Pamlico River. Adam’s most recent enslaver was John Maule, a wealthy land owner who inherited a large portion of his fortune from his father, the Scottish-born Dr. Patrick Maule.[2] Upon the death of John Maule in February 1774, Adam, along with 36 other enslaved people, were bequeathed to various members of Maule’s family and descendants.[3] Moses, John Maule’s son, inherited Adam and five other enslaved individuals, along with the title to a mill on Blounts Creek, and a nearby timber plot.[4]

As the North Carolina slave economy grew, the need to control a rapidly growing population of potentially rebellious enslaved people resulted in the passage of a series of laws and regulations, and most especially the omnibus law known as the North Carolina Slave Code. In 1741, the North Carolina General Assembly amended the Slave Code to stipulate that if a Freedom Seeker did not turn themselves in following the report of their escape, a member of the community was within their rights to “kill and destroy such Slave or Slaves by such Ways and Means as he or she shall think fit, without Accusation or Impeachment of any Crime for the same.”[5] This served as a daunting punishment for fleeing, and involved White community members in the capture of a Freedom Seeker while compensating the enslavers for their loss of property if an enslaved person was murdered. In 1753, following an alleged escape attempt, the North Carolina assembly had created a patrol system that appointed patrollers or sheriffs to search the residences of the enslaved for weapons, and to watch out for freedom seekers.[6] These patrollers were responsible for ensuring the enslaved were not collecting weapons with plans for mass escape or revolt, fears held by many White people in the colony.

The advertisement, posted five weeks after Adam’s escape, gives several hints about why this particular freedom seeker was threatened with death so soon after his escape. The first is in the way the advertisement lacks the financial reward customary of notices published to encourage the recapture and return of Freedom Seekers. Typically, these advertisements offered a financial reward for the arrest or capture of enslaved people that members of the White community would receive if they somehow participated in the capture. In contrast, this advertisement, or notice, offers no reward and instead calls on the white community to do their legal duty, as specified in the North Carolina Slave Code, making clear that the White public were both allowed and even expected to take violent action against Adam. Quoting the law, the notice specified that Adam might be “killed” or “destroy[ed]” by the “sheriff” or “any person” as “he or they may think fit.” These statements dramatically involved the community in the capture or murder of Adam, taking the unusual step of directly quoting the formal Slave Code.

The advertisement justifies this unusual course of action by referring to Adam’s supposed criminal nature, stating Adam is “lurking about; committing many Acts of Felony.” Crimes committed by enslaved peoples during this time were primarily thefts of food and goods to limit the burdens imposed by inadequate support from enslavers. Items like clothing were often stolen, along with livestock which was especially common amongst Freedom Seekers.[7] Perhaps Adam was looking for items to sustain himself while he was on the run or simply accused of these crimes to impose the rights entitled to the enslavers within the North Carolina Slave Code. However, it seems likely that his supposed crimes were more significant than the petty thefts that were more common. The notice in the newspaper relied on the power of the law and the legal obligation of white residents to halt any possible freedom attempt by inciting greater fears of Adam’s free existence in the community.

One can only hope that Adam found his way to freedom, because even if he were caught alive, he would have ended up in the slave courts. The court system, established by mandate in 1715 and amended in 1741, put a slave thought to have committed any crime on trial in front of three justices of the peace.[8] Slaves were often convinced to plead guilty, and if they didn’t the court would investigate the crimes. Being brought to trial did not always mean an enslaved person would be convicted, but in the event they were, punishment was brutal and violent.[9] The legal system was a way to control the enslaved population, and violence was a primary factor in maintaining the system.

Outside of the notice placed in The North-Carolina Gazette on March 9, 1775, there is no other mention of Adam. The possibilities of his escape range from safely joining the British Army, to capture by and likely death at the hands of North Carolina patrollers. If Adam had made it to safety without the help of the British, he may have ventured West or to more secluded areas of Virginia or South Carolina, both of which had large, maroon populations of free Blacks. The proximity of Beaufort County to the ocean may have allowed him freedom across the waterways. Given the little information we have, we cannot know exactly what Adams was alleged to have done between his escape on February 15 and the publication of this notice on March 24, 1775. Was he a violent criminal, or was the story more complicated? We have only part of one side of the story, and all we can say for sure is that in late March 1775, Adam was in in grave danger.

View References

[1] According to Marvin Michael and Lorin Lee Cary, most of those escaping slavery were between 20 and 35, and the escape of older individuals was far less likely. Marvin L. Michael Kay and Lorin Lee Cary, “Slave Runaways in Colonial North Carolina, 1748 – 1775,” The North Carolina Historical Review Vol 63 (1), (January 1986), 1-39.[2] Harry Z. Tucker, “Maule’s Point,” Our State; Weekly Survey of North Carolina, Vol 11 (12), (August 1943), 2, https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/state/985217?item=985228 [Last Accessed April 30, 2025]

[3] Using the will written of John Maule, the relative size of his plantation can be assumed. The names of people he enslaved, along with property, like land and livestock, are bequeathed to surviving family members. John Maule, “John Maule’s Will,” Beaufort County, North Carolina Archives, (February 1774), http://files.usgwarchives.net/nc/bertie/wills/maule.txt [Last Accessed April 30, 2025]

[4] John Maule, “John Maule’s Will.”

[5] Gabriel Johnston, William Smith and John Hodgson. Acts of the North Carolina General Assembly, 1741. Colonial and State Records of North Carolina. 1741), https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr23-0012 [accessed ????].

[6] According to Alan Watson, these patrollers would be exempt from county betterment projects (like road repair), but control of the program was by county, and some were better overseen than others. Alan D. Watson. “Impulse Toward Independence: Resistance and Rebellion Among North Carolina Slaves, 1750-1775.” The Journal of Negro History Vol 63, (4) (1978),317–28.

[7] Most of the crimes committed by the enslaved were thefts of necessity (food, clothing, livestock), according to Jeffrey Crow, but others included poisoning, arson, or murder. Jeffrey J. Crow, “Slave Rebelliousness and Social Conflict in North Carolina, 1775 to 1802,” The William and Mary Quarterly Vol 37 (1) (1980), 79-102.

[8] Alan D. Watson, “North Carolina Slave Courts, 1715-1785,” The North Carolina Historical Review Vol 60 (1), (1983), 24–36.

[9] According to Watson, the punishment for some crimes was given discretion while others had prescribed punishments. Towards the end of the 1750’s castration was used over execution in many cases, due to the costs of compensating slave owners. Other common punishments included whipping and ear cropping, and often other enslaved individuals were forced to watch as warnings. Watson, “North Carolina Slave Courts,.”