Billah’s story is one that includes several recurring themes in advertisements for freedom seekers. Concealed between the lines of the bulletin her enslaver had posted for the enslaved woman’s apprehension lies the interlocking subjects of memory, resistance, agency, and cultural resiliency. Like most stories about African Americans before emancipation, Billah’s is not simply a matter of black and white. Rather, hers represent a story of what R.G. Collingwood would describe as historical imagination. Because while many of the details regarding the fugitive woman’s life reside in several public notices published for her capture, others do not. In shades of gray, they can be found. That is to say, although less explicit, those details are just as real in what they document about Billah’s endeavor to own herself.[1]

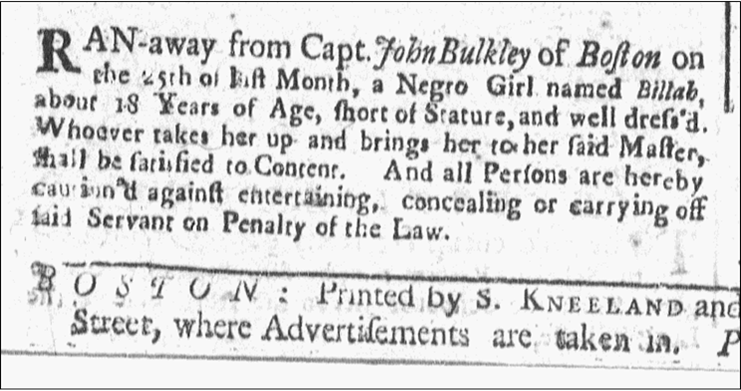

Her story begins on June 7, 1743. That summer, the first of several advertisements appeared in the Boston Gazette that would document at the very least three separate flights in the course of five years. Not surprisingly, the story these notices would reveal is multi-faceted. Like other freedom seekers, Billah’s story is one of slave resistance. If but for only a brief period of time, she owned herself. She pretended to be free. She denounced New England bondage with her feet.[2]

Like most runaways, Billah decided to leave when the weather got better. Determined to be her own master, she, like another freedom seeker named Silva, fled during the summer.[3] When she stole herself, the 18-year-old fugitive carried with her only the clothes she wore that day. She left, Bulkley explained, ‘well dress’d.’ If not a subtle invocation of paternalism, the captain’s observation about his woman’s clothing might have represented a moment of magnanimity. Unlike some of his contemporaries, he made sure his bondservant had adequate clothing. This much he felt willing to disclose to his neighbors. Still, despite her master’s generosity, she absconded, either in the dead of night or in the broad daylight.

Almost two weeks would pass before Bulkley went to the print shop on Queen Street, near his house. Prior to that visit, he probably opted to wait. Like most subscribers who placed runaway advertisements in the newspapers, the captain might have elected to give the fugitive time to return of her own volition. Or, before incurring the expense of placing a notice in the paper, he might have gotten the word out about his runaway through other avenues. If not by word of mouth, he might have posted a manuscript copy of the advertisement in certain public spaces, like taverns, ordinaries, and court yards. That might explain why many advertisements had two dates: the one in which they appeared in the newspaper, and other when they were penned.[4]

Regardless, Bulkley’s appeal to the public might have worked. Not long after the advertisement had been printed in the newspaper, deputized citizens may have discovered the fugitive’s whereabouts, taken her into custody, and collected their just reward. In the absence of additional documentation, however, it is equally plausible that the enslaved woman returned on her own volition. Left with only a few options in the manhunt generated by the printed notice, Billah might have elected to return to her enslaver’s place. There, she pleaded for leniency.

Whether she returned on her own volition or not, one thing is clear. By 1746, the fugitive woman had been back in Bulkley’s possession. The enslaver had been made whole again. Indeed, judging from subsequent advertisements that would appear later in the Boston Gazette, Billah decided, at least for a time, to stay put.

The détente the two observed came to an end on 13 October 1747. Almost four years had passed before Billah’s name remerged in the newspaper. Despite the coming of winter, she elected to run away again. Besides indicating that the fugitive woman had either been captured or that she decided to return to her enslaver on her own, the runaway advertisement printed in the newspaper on that occasion documented the woman’s determination, as well as additional facts. Billah, for example, survived smallpox. She also learned to speak the King’s English tolerably well. Like before, the fugitive left well dressed. “When she went away,” Bulkley explained in more precise terms, she had on “a purple and white Callicoe Gown, a red and white Callicoe Peticoat, [and] Wooden Heel’d Shoes.” The notice also outlined in more precise terms the reward for the fugitive. Besides “all necessary charges,” Bulkley promised: “three Pounds Old Tenor.” In the parlance of the day, the notice concluded much like the one before; “All Persons are hereby cautioned against concealing or carrying off said Negro on Penalty of Law.”[5]

In spite of the many uncertainties that lay before her, Billah persisted in her endeavor to be her own master. Shortly after being captured a second time or returning on her own volition, she ran away a third. Almost 10 months appears to have passed. During the last month of the summer of 1748, the fugitive woman left Bulkley’s place again. In addition to reporting the customary details regarding his runaway, the Boston enslllaver told his neighbors that his servant carried with her a new assortment of clothing. She wore, he reported, a ‘blue Jacket and a strip’d homespun Petticoat.’ Reflecting perhaps the fact that Billah was a few years older, Bulkley decreased the amount of the reward. In addition to “all necessary charges,” he offered the public modest compensation: 40 shillings, “old Tenor.” Two weeks passed. No news of Billah.

Apparently, the captain’s neighbors did not take the bait. By mid-October, rather than wait any longer, Bulkley returned to Kneeland and Green’s print shop. For two additional shillings, he changed the amount of the reward promised for the return of his bondservant: “Four Pounds, old tenor,” and, of course, “all necessary Charges.” Several more days passed. Still no news of Billah. For an additional two more shillings, Kneeland and Green reprinted the notice in their Boston Gazette.[6]

Presumably, Billah’s third flight might have proven the charm. Unwittingly, the town’s landscape might have aided the fugitive in her flight. Less than a mile from her master’s place on Queen Street, she may have made her way to the Long Wharf that extended into Boston Harbor. There, she could have stowed away aboard a ship anchored in the port and waited for the vessel to set sail. She could have also made her way further northward, perhaps toward one of the many shipyards in the town, where she passed for free or hired herself out. Considering the nature of most warnings included in runaway advertisements, it is possible that the woman found safe haven among some Boston do-gooders or sympathetic residents who considered slavery contrary to their religious beliefs. If not for religious convictions, like Samuel Sewall who wrote the antislavery pamphlet, The Selling of Joseph in 1700, some could have helped the fugitive because they thought the business of chattel slavery distasteful.

Then again, morality may have had very little to do with the matter. Because to a certain kind of shady, would-be employer, Billah’s flight might have offered them the opportunity of securing cheap labor at a rock-bottom price. It is also possible that the defiant woman had been taken up and sold to an enslaver who resided on a plantation in one of the southern colonies, if not somewhere in the British West Indies. It is equally possible that the fugitive had been taken up again and returned to her master who might have decided to sell her for her insolence. Ultimately, what became of the brave runaway slave woman is something of a mystery.

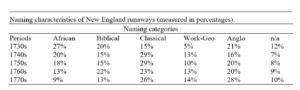

Besides the obvious, the story of Billah’s flights tells us another story, one almost hidden in plain sight. In that story, the enslaved woman wrote herself into history. That accomplishment represents no small feat considering her background. Judging from her age, her initial inability to speak the King’s English, and the fact that her master did not indicate that she had been born in the New World, the runaway slave might have been a native of Africa. Her unusual name certainly underscores the possibility of an African past. Of the hundreds of fugitives who absconded in New England during the eighteenth century, almost 20 per cent had African names.[7] Not to be confused with the name ‘Beulah,’ a Hebrew word that meant bride or married, or ‘Bilhah’ that meant ‘unworried’ or ‘bashful’ in Hebrew or even “Bilhah’ or ‘Balla,’ who had been Rachel’s maidservant, Jacobs’s concubine, and Rueben’s mistress in the Old Testament, the name Billah reflected not only the presence of Islam in West Africa, but also African traditions in which children were named for specific characteristics. A word of Arabic origin, the name signified not only a benediction, but also a clear expression of agency. Literally, it meant someone with God.[8]

Even though the rest of Billah’s background is hard to discern fully in the absence of additional documentation, another thing seemed apparent. She refused to obey. Like many other runaways, Billah repeatedly absconded. Over the course of five years, she left again and again. On at least three other separate occasions, she ran away; she demanded her freedom. Interestingly, each time, her master preserved the correct spelling of her name in print. Perhaps, as her name implies, God (Allah) might have truly been with her. She certainly appears to have reminded her enslaver of the correct elocution of her name.[9]

View References

[1] R.G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 239.

[2] Judging from the notices that appeared in print, Billiah ran away on at least two other occasions.

[3] Weather or work patterns clearly informed the times in which enslaved African Americans elected to run away.

[4] For an insightful history that examines the intersection of orality and print culture in early America, see Sandra M. Gustafson, Eloquence is Power: Oratory and Performance in Early America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012), xiii–xxv.

[5] Boston Gazette, November 3, 1747, 3.

[6] Boston Gazette, September 27, 1748, 2, Boston Gazette, October 11, 1748, 2; Boston Gazette, October 18, 1748, 2.

[7] Names mattered. Before emancipation, names signified a great deal in the Afro-Atlantic world. Intuitively, they communicated stories of resistance, agency, and cultural retentions.

Sources: Lathan A. Windley, Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History. New York: Greenwood Press, 1983. 4 vols; Billy G. Smith and Richard Wojtowicz, Blacks Who Stole Themselves: Advertisement for Runaways in the Pennsylvania Gazette, 1728–1790. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989; Graham Russell Hodges and Alan Edward Brown, ‘Pretends to Be Free’: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial and Revolutionary New York and New Jersey. New York: Fordham University, 1994; Antonio T. Bly, Escaping Bondage: A Documentary History of Runaway Slaves in Eighteenth-Century New England, 1700–1789. Maryland: Lexington Books, 2012; Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers Database; and, Eighteenth-Century American Newspapers in the Library of Congress in Microfilm.

[8] Maneka Gandhi and Ozair Husainly, The Complete Book of Muslim and Parsi Names (1994; repr., New York: Penguin Books, 2004), 90. Considering her African past, it stands to reason that the fugitive’s articulation of the difference more than likely informed Bulkley’s effort to secure his property.

[9] Billah’s persistence, that is the persistence of West African, Islamic traditions in the Atlantic world continued well into the nineteenth-century. Her story is but one of many. For a fuller account of the history of Islam in early America before emancipation, see Allan D. Austin, African Muslims in Antebellum America: A Sourcebook (Garland, 1984); Austin, African Muslims in Antebellum America: Transatlantic Stories and Spiritual Struggles (Routledge, 1997); Michael A. Gomez, Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in Colonial and Antebellum South (U of North Carolina Press, 1998); Sylviane Diouf, Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas (NYU Press, 2013).