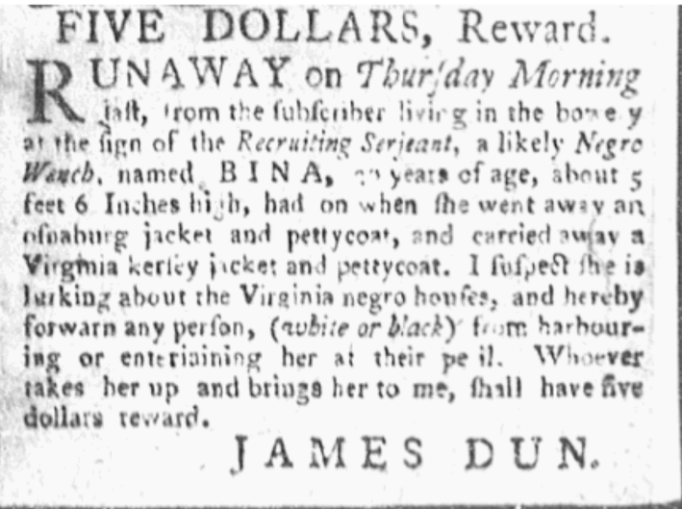

On the morning of Thursday, July 22nd, 1779, Bina slipped away from her enslaver’s residence on the outskirts of New York City. We cannot say for sure what inspired Bina’s decision. While she escaped by herself, she was one of a significant number of enslaved women who used the opportunity of wartime disruptions to seek freedom. As Graham Hodges and Alan Brown note, many more women fled enslavers during the wartime years of the American Revolution than during the period before or after.[1] She escaped nearly three years after the Continental army had lost the city and port of New York. But while Britain’s occupation of the city delivered a massive blow to Patriot morale, it opened a window of opportunity for people of African descent like Bina.

Bina did not take much with her, just an extra set of clothes in addition to what she was wearing. Fired by adrenaline, fearful and excited in equal measure, she would need to steady her nerves or risk arousing suspicion. If she followed the Bowery Lane north, she would have ended up along the post road to Boston. But it seems more likely that she headed south, determined to disappear into the more populated southern tip of the city. As she navigated towards the North River, perhaps she waited until the familiar Bowery landmark of Bayards windmill had grown distant before finally allowing herself a moment to catch her breath.[2]

We do not know where Bina was born or grew up. The advertisement offers one clue that suggests she came to New York from the Upper South. The woolen jacket Bina took with her was either made in Virginia or was in a style common in the Old Dominion. Unlike her osnaburg jacket, which could be purchased almost anywhere, the kersey jacket was homespun fabric made by Virginians who were determined to avoid importing textiles from Britain by making their own. Bina’s enslaver, James Dun, believed that the distinctive fabric might help to identify her. Supporters of the Patriot cause proudly wore their homespun clothing as a sign of their defiance towards the British.[3] It seems doubtful that Bina shared this sensibility. But while the jacket might have threatened to expose her, Bina carried it with her, nonetheless, a familiar item of clothing and one of the very few personal items she decided to keep.

James Dun suspected Bina had another connection to the Chesapeake. In his efforts to locate the escaped 20-year-old woman, Dun suggested she would be “lurking about the Virginia negro houses.” This intriguing note was almost certainly in reference to the remnants of Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment. Three years earlier, in the aftermath of his failed efforts to retake the city of Norfolk, Lord Dunmore had retreated to New York City. He brought with him hundreds of Black men, women, and children, all of whom had heeded his now well-known proclamation and sought freedom by escaping to join his forces. They arrived in New York as refugees and lived in racially segregated barracks. These were concentrated on the western side of Lower Manhattan. Black recruits lived with their families at 18 Broadway, 10 Church Street, 18 Great George Street, 8 Skinner Street, and 36 St. James Street.[4] This poorer part of the city retained the marks of the massive 1776 fire that had destroyed nearly a quarter of New York. The modest dwellings established upon this scorched landscape were crude structures, made from canvas and any other materials that could be scavenged. Other barracks established across the East River near the wagon yard in Brooklyn were just as makeshift. Yet as Cassandra Pybus reminds us, despite the conditions, the Black people who inhabited these barracks formed communities that were “bound together by struggle.”[5] If Bina was indeed from Virginia she may have known and even had familial connections with residents of the “Virginia negro houses,” but whether or not she was directly connected with any of these people she had plenty in common with them. Perhaps she had managed to create connections there while still enslaved by Dun, and when the opportunity arose, she had escaped to join them. Or maybe Bina simply knew this area would make a good place to hide.

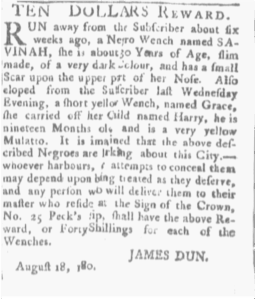

James Dun, Bina’s enslaver, was a Loyalist. The warning in his advertisement to “any person” whether they be “white or black” to not harbor or entertain Bina offered a clear declaration to the Black population of New York that they owed the same fealty to the laws of Great Britain as any other of the king’s subjects. While proclamations from Lord Dunmore and later Sir Henry Clinton promised “full security” to the enslaved who deserted the “Rebel Standard,” the human property of Loyalists was supposedly sacrosanct.[6] In addition to Bina, Dun enslaved two other women of African descent, one named Savinah and the other named Grace.[7] About five months before Bina decided to escape, Grace had given birth to a boy named Harry who shared his mother’s “yellow” complexion and mixed-race background. If James Dun was Harry’s father, it was because he believed his property rights and patriarchal authority gave him power over Grace’s body. The realities of rape and sexual assault drove many women like Bina to seize their opportunities for freedom: perhaps all three of these women were vulnerable to Dun’s sexual predation.

A little over a year after Bina escaped from James Dun, Savinah, Grace, and Harry followed in her footsteps. As he imagined Savinah, Grace, and her son Harry also “lurking about this City” he perhaps despaired that New York had become a haven for those who sought freedom within the chaos of British occupation. We do not know whether Bina, Savinah, Grace, or Harry found success in their bids for freedom. When the British finally began to withdraw from New York City they evacuated thousands of Black refugees to Nova Scotia and recorded their names in what has become known as “The Book of Negroes.” Several women named Bina found refugee aboard these British ships.[8] It is impossible to positively identify any of these women as being the Bina who fled the Bowery to hide amongst New York’s Black Loyalists. But what is much more certain is that when General George Washington finally reentered the city in 1783 and he stopped at the Bull’s Head Tavern in the Bowery, where Bina had first escaped, she was very likely not there.

View References

[1] Alan Brown, Graham Hodges, “Pretends to Be Free”: Runaway Slave Advertisements from Colonial and Revolutionary New York and New Jersey (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019) xxxiii.

[2] Bayard’s windmill was located in the Bowery, very close to the Bull’s Head Tavern. The “sign of the recruiting serjeant” mentioned in James Dun’s advertisement for Bina likely referred to this well-known establishment. An advertisement published in the Royal Gazette months earlier instructed recruits interested in serving in his majesties “loyal American regiment” to report there. See “Advertisement.” Royal Gazette (New York, New York), April 10, 1779.

[3] Neal Hurst, “Made in American: Resistance through homespun and the rise of American textile manufacturing,” https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/discover/resource-hub/trend-tradition-magazine/trend-tradition-spring-2018/made-in-american/ [accessed August 20, 2025].

[4] Thelma Wills Foote, Black and White Manhattan: The History of Racial Formation in Colonial New York City (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004) 213.

[5] Cassandra Pybus, Epic Journeys: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and their Global Quest for Liberty (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006) 32.

[6]“Advertisement” New-York Gazette, and Weekly Mercury (New York, New York), July 26, 1779. Sir Henry Clinton’s proclamation appears in the same issue of the New-York Gazette, and Weekly Mercury as Bina’s advertisement.

[7] Royal Gazette (New York, New York) August 19, 1780. My thanks to Melanie Sanchez for bringing this advertisement to my attention.

[8] Book of Negroes (1783), Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester: Papers, The National Archives, Kew (PRO 30/55/100) 10427, https://archives.novascotia.ca/africanns/book-of-negroes/results/?Search=Bina [accessed August 25, 2025].