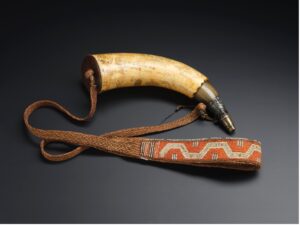

He could not be contained or restrained. Young, far from home and alone, he escaped at least four times between September 1764 and August 1766, and Edinburgh and Glasgow newspapers published seven different advertisements seeking his capture and return.[1] In the first of these he was described as “an INDIAN young LAD,” later as an “INDIAN BOY” or “INDIAN LAD,” and finally as a “TAWNY NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN BOY” named Bob. The Seven Years’ War, which France and Britain had fought across the world but most especially in North America, had ended in 1763, and it may well be that Bob had been captured following British victories in western Pennsylvania, New York, and New England, and the conquest of French Canada. This conflict played a pivotal role in drawing Scotland into Britain and the British Empire, and Scottish soldiers fought in large numbers, with several Highland regiments serving. The 77th Highland Regiment, for example, saw action in New York’s Mohawk Valley, and the 77th, the 78th Highlanders, and the Royal Highland Regiment all fought in French Canada. James Cameron was a member of one Scottish regiment, and his carefully carved powder horn is attached to an Indigenous-made strap of moose hair. Dated 1758, it is a powerful symbol of the interactions between Scottish soldiers and Indigenous people during the Seven Years’ War.

Bob’s story was extraordinary but not completely unique. Following the British victory at Fort Ticonderoga in 1759, Major General George Townshend brought an Odawa boy with him to London. The unnamed boy was described in a letter by the poet Thomas Gray:

he has brought home an Indian Boy with him (design’d for Ld G: Sackville, but he did not chuse to take him) who goes about in his own dress, & is brought into the room to divert his company. the Gen:l after dinner one day had been shewing them a box of scalps & some Indian arms & utensils. when they were gone, the Boy got to the box & found a scalp, wch he knew by the hair belong’d to one of his own nation.[2]

Perhaps Bob had also been brought back by a Scottish army officer.[3]

It is unclear who claimed ownership of Bob. All of the advertisements published in the Edinburgh Evening Courant, as well as the first advertisement in the Glasgow Journal, indicated that a reader who captured the young boy could return him to “the printer of this news-paper” who would serve as a middle-man to “get” payment from Bob’s enslaver. Enslavers placing advertisements like this one often relied on printers in this fashion: the location of the printer’s office appeared in every issue, and there was almost always somebody in these offices during the working day. However, the two advertisements published in August 1766 directed readers who captured Bob to bring him to “Claud Marshall, writer in Glasgow.” The language did not suggest that Marshall was a middle-man, and it is possible that he was in fact the enslaver who claimed ownership of Bob. Marshall was a Glasgow writer or lawyer, and his work brought him into contact with merchants, officials, and most likely soldiers involved with British North America. Perhaps he had purchased Bob or received him in payment of legal fees. Ownership of an enslaved boy had long served as a means of communicating financial success.[4]

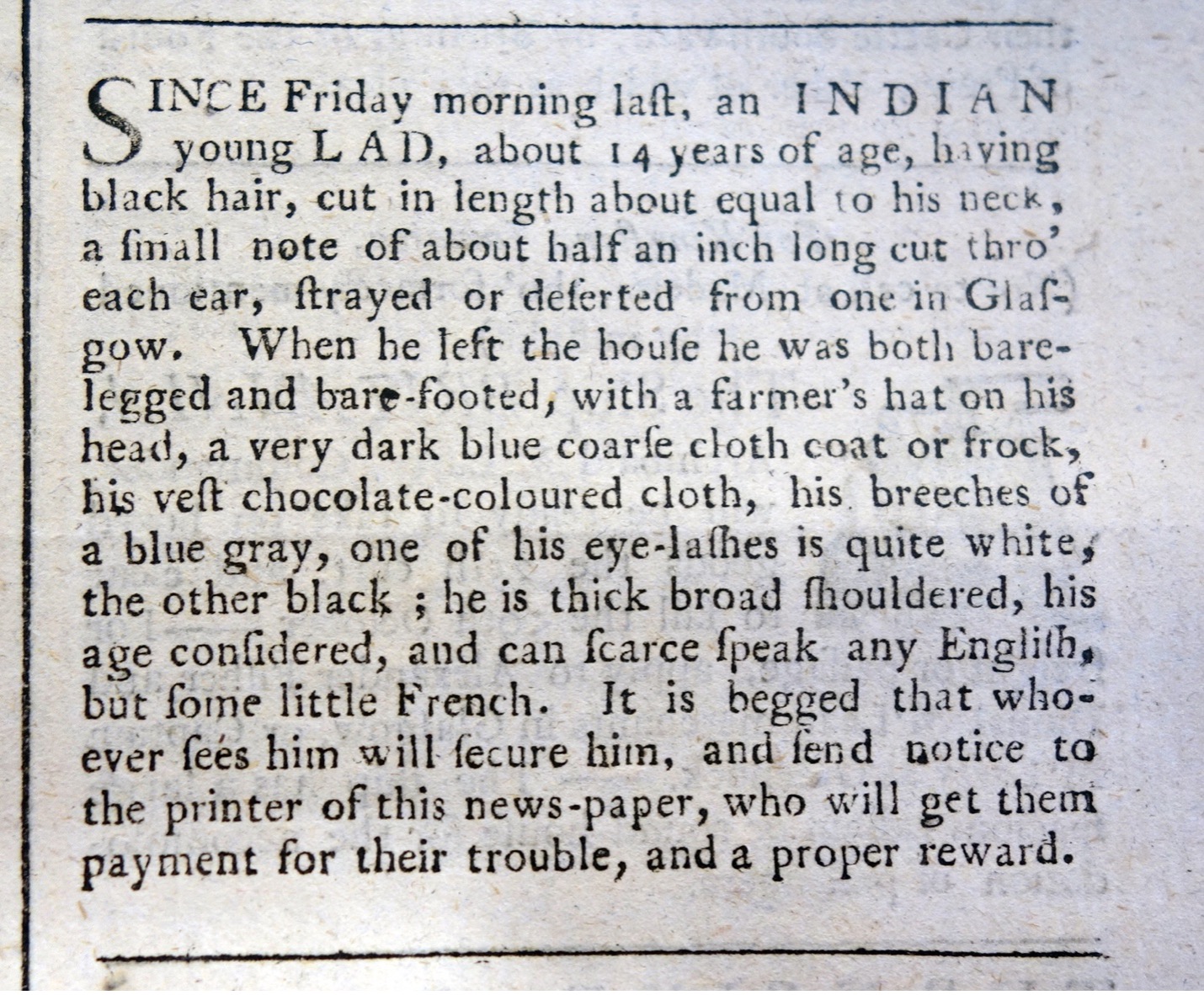

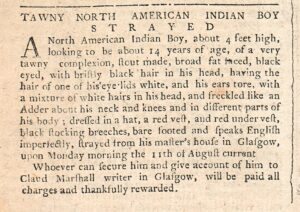

We know relatively little about Bob. Although the first and last advertisement were almost two years apart, he was described in most of them as being about fourteen years old, and in one as about thirteen, “but pretty big” for his age.[5] The earliest advertisements indicated that Bob “can scarce speak any English, but some little French,” while two years later an advertisement did not mention French and stated that he “speaks English imperfectly,” If Bob had been brought from Canada or the lands to the west of the northern colonies, he had arrived with little English but was slowly learning more.[6]

Bob was given simple clothing similar to that worn by other working people in Glasgow. The first advertisement for him recorded that he escaped wearing a farmer’s hat, a dark blue coarse cloth coat, a chocolate-colored vest or waistcoat, and blue gray beeches. The second time he eloped he wore the same vest, along with a brown coat, worn black breeches, white worsted stockings and a shabby hat, and in all of the advertisements Bob was described as wearing clothing of this type.

Despite his humble attire, the descriptions of him suggest that Bob stood out as different from the Glaswegians around him. Several of the advertisements referred to his “tawny” complexion, and in five of the seven advertisements he was described as “bare footed” and bare-legged. Indigenous North Americans were used to wearing either thin and supple leather moccasins or no footwear at all, and the inflexible thick leather shoes and boots worn by working people in Scotland may well have felt extremely uncomfortable. Bob had a large hole in each ear, quite likely for the carved stone, shell, or even copper earrings made and worn by people of the Northeastern woodlands. With short black hair, black eyes, and one eyebrow black and the other white, and freckled skin, Bob’s appearance was distinctive. Glasgow was home to fewer than twenty-four thousand inhabitants in 1755, a number that had surely increased a decade later, but the city was small enough for an Indigenous North American boy to stand out. Marshall lived and worked at the southern edge of the developing Merchant City, close to the major thoroughfare and location of many mercantile and legal businesses on Trongate: at one point, for example, he was based in Laigh Kirk Close, a small alley immediately below Trongate. A photograph of the pedestrian alley taken just over a century later reveals a narrow, intimate close that had changed little over the intervening years. In this small but growing city, Bob would have made an impression.[7]

Bob was almost certainly a name given to him by one of the Britons who trafficked him, and we have no idea what his actual name was, or from which Indigenous community he came. He seems to have arrived in Scotland shortly before he first escaped in September 1764, at which point he spoke little English. How alone he must have felt, thousands of miles from the place of his birth and the people of his community? How strange the Scottish city must have seemed. He did not settle, attempting to escape regularly, until the final advertisement for him appeared in a Glasgow newspaper on August 14, 1766, three days after Bob had eloped. Was he once again recaptured, and did he not attempt escape again? Perhaps his frustrated enslaver sent him back to North America or the Caribbean, to be sold as a slave or bound servant. Maybe Bob’s escape was successful, and he tried to make a new life for himself, finding work or joining the crew of an ocean-going ship. Or perhaps he died, and was laid to rest in an unmarked pauper’s grave, far from home and mourned by nobody. Whatever his fate, Bob epitomizes the alienation and loneliness of many who were enslaved and bound, separated from everything and everyone they knew, desperately holding on to elements of their culture and identity.

View References

[1] The first recorded escape was on either 20 or 21 September, 1764, prompting advertisements in the Edinburgh Evening Courant on September 26, 1764 and in the Glasgow Journal on September 27, 1764. He eloped again on14 June 1765, resulting in a single advertisement in the Edinburgh Evening Courant on June 17, 1765. A few months later, on September 4, 176, he escaped again and advertisements for him appeared in the Glasgow Journal on September 5, 1765, and in the Edinburgh Evening Courant on September 9, 1765. The final recorded escape was nearly a year later on August 11, 1766, with advertisements appearing in the Edinburgh Evening Courant on August 13, 1766, and in the Glasgow Journal on August 14, 1766.

[2] Thomas Gray to Thomas Wharton, January 23, 1760. Egerton MS 2400, ff. 128-129, Manuscripts collection, British Library. Reproduced in Thomas Gray Archive, https://www.thomasgray.org/texts/letters/tgal0355#ft [accessed September 9, 2025]. I am grateful to Matthew Dziennik for this reference.

[3] For Scottish participation in the conflict see Colin G. Calloway, White People, Indians, and Highlanders: Tribal People and Colonial Encounters in Scotland and America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 88-116; Matthew P. Dziennik, The Fatal Land: War, Empire, and the Highland Soldier in British America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015); and Andrew Mackillop, More Fruitful than the Soil: Army, Empire, and the Scottish Highlands, 1715-1815 (East Linton, Scotland: Tuckwell, 2000).

[4] “SINCE Friday morning last, an INDIAN young LAD,” Edinburgh Evening Courant (Edinburgh), September 26, 1764; “A North-American Indian Boy,” Edinburgh Evening Courant (Edinburgh), August 13, 1766; Glasgow Journal (Glasgow), August 14, 1766. Evidence of Marshall’s work for such people can be found, for example, in the archives of the Glasgow Trades House: see Trades House of Glasgow, Archival Boxes, 1732 to 1960s, Inventory, The Trades House Digital Library,http://www.tradeshouselibrary.org/uploads/4/7/7/2/47723681/archives_brown_box_1_to_39_complete.pdf [accessed 8 Sept 2025]. For more on the ownership and public display of enslaved boys as emblems of success, see for example Simon P. Newman, “Freedom-Seeking Slaves in England and Scotland, 1700-1780,” English Historical Review, 134 (2019), 1138-40.

[5] “ON the 14th instant, an INDIAN BOY,” Edinburgh Evening Courant (Edinburgh), September 9, 1765.

[6] “SINCE Friday morning last, an INDIAN young LAD,” Edinburgh Evening Courant (Edinburgh), September 26, 1764; “TAWNY NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN BOY,” Glasgow Journal (Glasgow), August 14, 1766.

[7] “A North-American Indian Boy,” Edinburgh Evening Courant (Edinburgh), August 13, 1766. For more on indigenous earrings see Lois Sherr Dubin, North American Indian Jewelry and Adornment: From Prehistory to the Present (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999), 166-8. For Glasgow’s population numbers see John Sinclair, The Statistical Account of Scotland, 1791-1799: VIII, Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire, (1845), (East Ardsley, Wakefield: E.B. Publishing Ltd., 1973), xxxiv.