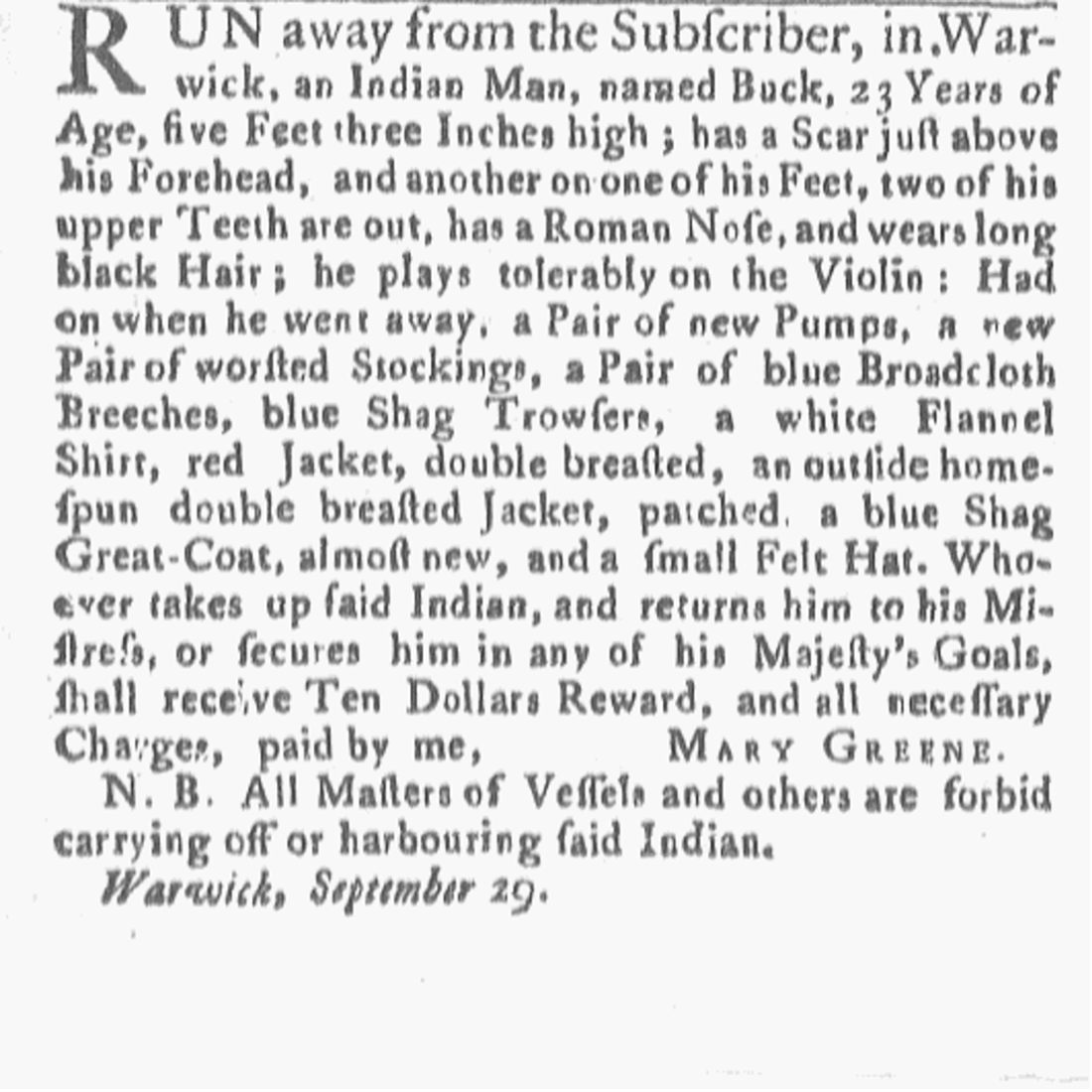

Buck was young, just twenty-three years old, and identified as an “Indian Man” from the town of Warwick, Rhode Island. Some ten miles south of Providence, Warwick was a community of fewer than 2,500 people. Of these, eighty-nine were of African and eighty-eight of Indigenous ancestry. Buck was most likely enslaved, like many of these Indigenous and Black people. Although Warwick’s Indigenous and Black populations were almost exactly equal in size, it is quite possible that Buck was the only Indigenous person in a large household of twenty people, outnumbered by the five Black and fourteen White residents. Like so many enslaved people in New England, he may well have lived apart from his own people.[1]

Perhaps this isolation helps explain why Buck escaped in September 1773. He remained free for at least a month, perhaps longer, since the first advertisement seeking his recapture appeared in the Providence Gazette on October 30, 1773. It repeated in the Gazette a week later, but after that Buck disappears from the records, either because he was recaptured or because his bid for freedom was successful. He had escaped from the household of Mary Almy Greene, the widow of John Greene who had died a decade earlier. Mary was fifty years old when Buck escaped. Despite her age, the 1774 Rhode Island census recorded that she was mistress of a large household of twenty people. Only one of these six was recorded as “Indian”: was this Buck, who had been recaptured, or another Indigenous person? Mary Almy Greene died three years later, and the first Federal census in 1790 recorded that Benjamin, her eldest surviving son and heir, had two “slaves” in his household, but it is unclear who they were.[2]

The 1774 census revealed that more than one-third of Rhode Island’s Indigenous population lived in White households. The records do not reveal what proportion was enslaved, but the newspapers regularly featured advertisements that either identified Indigenous freedom seekers as enslaved, or offered them for sale. Most enslaved Indigenous people engaged in agricultural or household labor, although a few developed artisanal skills. Mary Almy Greene described Buck as being twenty-three years old, a fairly precise number when compared with the many advertisements that gave estimates of age-ranges for enslaved people who enslavers had known for only a relatively short period. This may suggest that Greene had known Buck since his childhood, and perhaps he had been born to an enslaved mother in the Greene family household. We do not know his origins, but he may have well been Narragansett, a label that encompasses the various Algonquian people of southern New England. If he had been separated from his own people, then Buck would have been raised in and learned the language and ways of Anglo-American colonists, and of the enslaved Africans who labored beside him.[3]

Was Mary Almy Greene highlighting physical characteristics that White folk associated with Indigenous people when she described his “Roman Nose” and then reported that he “wears long black Hair”? His clothing, however, was exactly what many White men would have worn: pumps, new worsted stockings, blue broadcloth breeches or blue shag trousers, a white flannel shirt, a red jacket, an older patched outer coat, and a small, felted hat. There is no indication of how he got the scars on his forehead and foot, or how he had lost two of his upper teeth, but perhaps these were the marks of years of physical labor. His name, Buck, had quite likely been applied by White enslavers or masters, and if he had been given a different name by his parents we no longer know what it was.

Perhaps the single clearest indication of Buck’s multi-cultural identity is the short phrase in the middle of the advertisement indicating that “he plays tolerably on the Violin.” Music was an essential part of Indigenous life and culture, often spiritual in nature, and usually performed in groups as part of community social rituals. But much of this music was choral, with singing and chanting often accompanying dancing, sometimes with rhythmic percussion, but very often without any kind of instrumental accompaniment. Indigenous Americans in the New England area had no musical instruments like the violin or fiddle, and so Buck had learned to play an instrument familiar to both Europeans and West Africans. It is very possible that Buck had learned the fiddle from enslaved African Americans, who drew on both Euro-American musicality and their own rich musical heritage. By one count, one of every ten men who fled enslavement in eighteenth-century New England took a violin with them. Black men thus frequently played the fiddle, performing both European tunes and music from their emerging African American culture. Thomas Jefferson was an accomplished violin player, as were Beverly, Eston, and Madison, his enslaved sons with Sally Hemings. Later in life as a free man Eston Hemings was an accomplished violinist who acted as a caller of dances at social gatherings and community events.[4]

Choosing to take a fiddle as one of the few items that he could carry suggests the importance of music to Buck. In practical terms, he could play in taverns or on the streets to busk for money to support himself both while enslaved and during his escape. In personal terms, his identity as a musician may well have provided him a great deal of comfort. What did this violin and the music that he played mean to Buck? Did he play for himself or for others, and what did he play? Did he play, as sometimes happened, dance tunes for Blacks, Whites, and Native peoples? What does this tell us about his sociability and his place in the larger, mixed-race community? We cannot know for certain. Perhaps his violin-playing indicates how Buck had been drawn into the culture and society of the Greene family and their larger mixed-race community. Could he recall the language and musical forms of his original birth community, particularly if he had maintained contact with family and Indigenous community members? And, like many people who challenged slavery, was he able successfully to select and combine bits and pieces from the various cultures in which he lived? If his escape was successful, or if he secured freedom in the dislocation of the revolutionary era, he may have sought to make his way to his Indigenous family and community, but it is just as likely that he forged a life for himself within White society. Wherever Buck went, his violin and his music went with him.

View References

[1] See “Buck,” in Stolen Relations: Recovering Stories of Indigenous Enslavement in the Americas” https://stolenrelations.org/referents/0e0da1be-40a6-4a3b-ad8e-878e14199815/ [accessed May 28, 2025]. “Recapitulation of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rode Island,” and entry for “Greene, Mary Widow,” Warwick, Rhode Island in Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and providence Plantations, Taken By Order of the General Assembly, In The Year 1774, arranged by John Bartlett, (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), 239, 62.

[2] Louise Brownell Clarke, The Greenes of Rhode Island. With Historical Records of English Ancestry, 1534-1902 (New York: 1903), 111-2; Census of the Inhabitiants of the Colony of Rhode Island, 62; Entry for Mary Almy, 1722-1777, Family Search, https://ancestors.familysearch.org/en/MKB2-X43/mary-almy-1722-1777 [accessed April 9, 2025]; Entry for Benjamin Greene, Warwick Town, Providence County, Heads of Families At the First Census of the United States in the Year 1790. Rhode Island (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907) 15.

[3]See, for example, “RUN-AWAY from their Masters… two Negro Men, and one Indian Man, Slaves,” Newport Mercury (Newport), November 11, 1765; “”RAN away from the Subscriber… an Indian Fellow named Peter,” Newport Mercury (Newport), July 4, 1768. For more on labor, see John A. Sainsbury, “Indian Labor in Early Rhode Island,” New England Quarterly, 48 (1975), 378-393.

[4] Robert B. Winans, ed., Banjo Roots and Branches (Urbana: Univeresity of Illinois Press, 2018), 195-200; Annette Gordon-Red, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family (New York: W.W. Norton, 2008), 97, 262, 602; “A Spring of Jefferson was Eston Hemings,” Scioto Gazette (Chillicothe, Ohio), August 1, 1902. For Indigenous music see Christine DeLucia, “The Sound of Violence: Music of King Philip’s War and memories of Settler Colonialism in the American North,” Commonplace: The journal of early American life, 13 (2013), https://commonplace.online/article/sound-violence-music-king-philips-war-memories-settler-colonialism-american-northeast/ [accessed April 7, 2025]; Gary Tomlinson, The Singing of the New World: Indigenous Voice in the Era of European Contact (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007); and Olivia Ashley Bloechl, Native American Song at the Frontiers of Early Modern Music (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008).