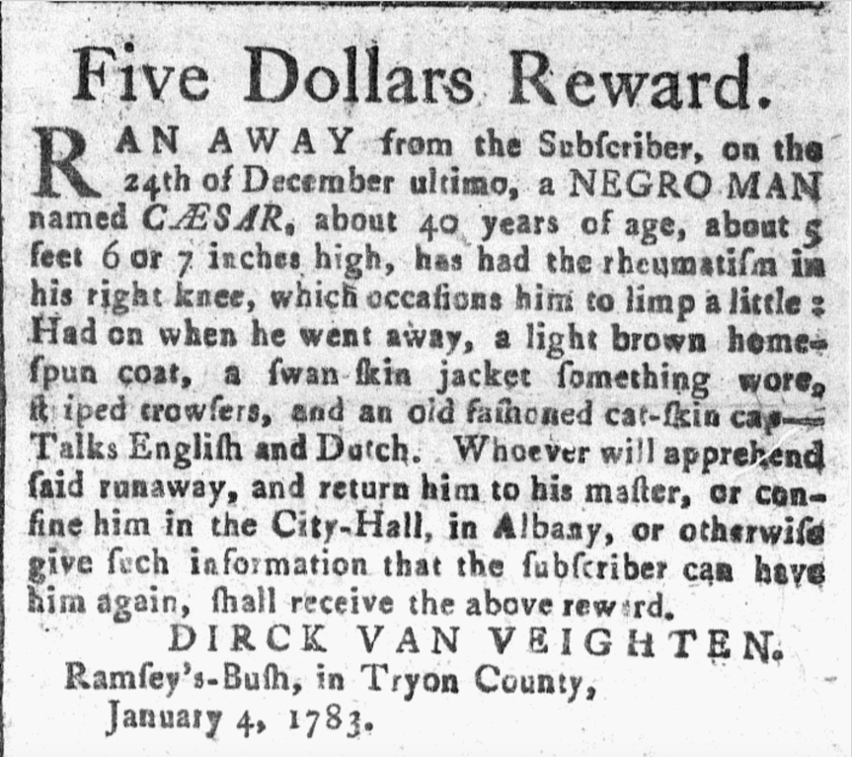

On Christmas Eve, 1782, a forty-year-old enslaved man named Caesar ran away from his owner’s farm in the upper Hudson River Valley of New York State. He was “about 5 feet 6 or 7”—about average height for the time period—and had a slight limp due to “rheumatism in his right knee.” He wore a home-spun coat, a swan skin jacket, striped trousers, and an “old fashoned cat-skin cap.” As was common among slaves in this region, Caesar spoke both Dutch and English. The man who owned Caesar, Dutch-descended Dirck van Vechten of “Ramsey’s-Bush, in Tryon County,” placed an advertisement in an Albany newspaper, hoping that someone would either return Caesar, confine him in the Albany City Hall, or provide information so that “the subscriber can have him again.”[1]

It is possible that Caesar managed a permanent escape. The Van Vechtens lived in a rather remote agricultural area about thirty miles northwest of Albany, just south of the Mohawk River. “Ramsey’s-Bush” is a now obscure place name that likely denoted the site of the Van Vechtens’ farm.[2] By the time Van Vechten managed to get word to the newspaper’s editors on January 4, Caesar had been gone a while. The paper reprinted the runaway notice for several weeks, which further suggests that Caesar eluded capture, at least in the short term. Thus far, I have not been able to find another trace of Caesar. If he managed to establish a life apart from the Van Vechtens, it is possible he changed his name to protect against re-enslavement. He might also have changed his name because “Caesar” was not the one his parents gave him. Perhaps the man formerly called “Caesar” slipped quietly into one of the communities of free black people that were steadily growing in the northern American states in the wake of the Revolutionary War. Or, if we consider the possibility that he decided to keep his name, “Caesar” does not make locating him in the records easy; the name was ubiquitous among the local enslaved and free black population.[3] But of course, Caesar’s escape might have been temporary. Van Vechten might have successfully reclaimed the man who was, by law, his chattel property.

Despite the mysteries surrounding Caesar’s flight, exploring the world in which he lived can help us understand why he might have run away when he did, where he might have gone, and why. Slavery was widespread in the Hudson River Valley, which had been governed by the Dutch Republic before the English wrested control of the region in the late 1600s. The labor of people like Caesar enabled white settlers to engage in the fur trade with local Indigenous nations, including the Haudenosaunee (called the Iroquois by the French); to move food (especially grain) and other commercial goods up and down the Hudson River; and to participate in the wider Atlantic economy.[4] Despite the prevalence of slavery, the number of slaves in each household was relatively small, and physical living arrangements were tight, which meant that bound people were intimately exposed to Dutch culture. As one scholar of Dutch American slavery has noted, “enslaved and free black people in these communities often spoke the Dutch language, worshipped in Dutch Reformed churches, and ate Dutch American foods.”[5]

The Dutch context might help us make sense of why Caesar chose to flee on Christmas Eve. The Dutch traditionally treated the time between Christmas and New Year’s as an extended holiday season. Revelers drank beer and baked seasonal treats. In the countryside, families went skating, tobogganing, and sleigh-riding.[6] Were a man like Caesar intent on running away when masters and local officials were distracted, late December was a good moment. It was also incredibly cold this time of year where Caesar lived; he might have suspected there would have been fewer people out and about to spy him as he made his escape.

But why 1782? Caesar would likely have been aware in December of 1782 that the Revolutionary War was coming to an end. Patriot soldiers and officers—including Van Vechten—would have been trickling home, and white families would have been adjusting to post-war realities. Maybe Caesar especially disliked Van Vechten, and knowing the household patriarch would be making a permanent return after seven years of service was Caesar’s motivation to flee.[7] Or perhaps Van Vechten had only recently purchased Caesar from, say, one of his Van Vechten cousins or from another Dutch connection in the Hudson Valley, and Caesar resented the new arrangement.[8]

The timing of Caesar’s escape also fits within a wider pattern. Scholars have noted an uptick in the number of enslaved people who took flight in the region during and after the Revolution.[9] The evidence comes not only from runaway advertisements in newspapers, but family papers as well. For example, two years after Caesar ran away, one of Dirck van Vechten’s Albany cousins instructed business associates to sell “my Negro Wench” as soon as possible because “I am afraid that she will run.” Other papers generated by families in the region show evidence of similar dynamics.[10] Caesar would almost certainly have moved within circles of enslaved kin and friends in the Hudson Valley who knew people who had run off, who were informed of where these people had gone, and who had heard reports of how they had managed their escapes.[11]

In 1790, Dirck van Vechten reported to a federal census taker than he owned one slave.[12] It is possible this was Caesar. It is also possible that Caesar was long gone, having made his way to New York City, Vermont, western Massachusetts, or Canada—all places where he would have encountered robust free communities of color and significant numbers of antislavery white citizens. We will likely never know, but the possibilities are nonetheless worth considering. Caesar, like many people of African and of European descent in the Hudson Valley, saw opportunities for different and better futures during the American Revolution. Wherever it was that Caesar found himself on Christmas Day, 1782, it was not with Dirck van Vechten.

View References

[1] I thank BJ Lillis for reviewing this piece and assisting me with Dutch naming practices; Eric Ryu for helping me transcribe Dirck van Vechten’s pension records; Kelly Yacobucci Farquhar, the Montgomery County Historian, for research support; Scott Heerman for fruitful consultation; and Gloria McCahon Whiting and Simon P. Newman for their editorial care. On the prevalence of the Dutch language, see Michael J. Douma, “Estimating the Size of the Dutch-Speaking Slave Population of New York in the Eighteenth Century,” Journal of Early American History 12 (2022), 3-35. Note that Dirck van Vechten’s first and last names are spelled multiple ways across various archives.There has been much conversation of late about the terminology scholars use when writing about slavery and enslaved people. In general, I follow the guidance of the following historians, who express preferences for certain terms while also making the case for flexibility. Different historical contexts and methodologies may not all require the same language. As Leslie Harris notes, it’s not the terms themselves that tell us single-handedly whether “the work of humanity is clearly in the body of the whole [article or book].” Leslie M. Harris, “Names, Terms, and Politics,” Journal of the Early Republic (Spring 2023): 149–154; Tiya Miles, All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, A Black Family Keepsake (New York: Random House, 2021), 277–289; Dylan C. Penningroth, Before the Movement: The Hidden History of Black Civil Rights (New York: Liveright, 2023), xxvii–xxviii.

[2] There is a place now called “Remsen Bush” near the site of the Van Vechten farm, which sounds similar to “Ramsey’s Bush.” Alternatively, “Ramsey’s-Bush” might be the place that was later called “Scotch Bush,” an existing hamlet near the farm in what became the Town of Florida. The Ramseys were early Scottish settlers.

[3] For an example of a free man, see Caesar Wanton, 1790 Federal Census, South Ward, New York, New York. For an example of an enslaved man, see “Ten Dollars Reward,” Greenleaf’s New York Journal, and Patriotic Register, August 26, 1796. On growing free communities in the late 1700s, see Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003). For the mid-Hudson, see Michael E. Groth, Slavery and Freedom in the Mid-Hudson Valley (Albany: SUNY Press, 2017), 62-63. For Albany, see Sarah L. H. Gronningsater, The Rising Generation: Gradual Abolition, Black Legal Culture, and the Making of National Freedom (Philadelphia: Penn Press, 2024), ch. 3.

[4] A. J. F. Van Laer, editor and translator, Van Rensselaer Bowier Manuscripts (Albany: University of the State of New York, 1908), 715; BJ Lillis, “A Valley between Worlds: Slavery, Dispossession, and the Creation of a Settler-Colonial Society in the Hudson Valley, 1659-1766” (PhD diss. Princeton, forthcoming).

[5] Andrea Mosterman, Spaces of Enslavement: A History of Slavery and Resistance in Dutch New York (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021), 5. See also Nicole Saffold Maskiell, Bound by Bondage: Slavery and the Creation of a Northern Gentry (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2022).

[6] Bayard Tuckerman, Makers of American History: Peter Stuyvesant… (New York: The University Society, 1904), 151-52; Jaap Jacobs, The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth Century America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), 466.

[7]Derick van Vechten or van Veghten Pension Records, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land-Warrant Application Files, National Archives Microfilm Publication, Roll 2451, National Archives and Records Administration.

[8] In the first federal census, recorded in 1790, one of Dirck van Vechten’s cousins reported seven slaves in his Catskill household, and another of Dirck’s cousins reported two slaves in his Albany household. Samuel van Vechten, 1790 Federal Census, Catskill, Albany County, New York; Teunis T. van Vechten, 1790 Federal Census, Albany Ward 3, Albany County, New York.

[9] Mosterman, Spaces of Enslavement, 66-67; Groth, Slavery and Freedom in the Mid-Hudson Valley, ch. 2, 62-63; Susan Stessin-Cohn and Ashley Hurlburt-Biagini, In Defiance: Runaways from Slavery in New York’s Hudson River Valley, 1735-1831 (Delmar: Black Dome Press Corporation, 2016).

[10] Robert Donnell to John Roseboom, care of John Ten Broeck, West Camp, July [?] 1782, Van Vechten Legal Papers, New York State Library; Teunis T. Van Vechten to Mssrs. Stewart and Jones, Merchts, New York, August 6, 1785, OCLC/NY ID 1099693504, New York State Library.

[11] This interpretation is inspired by Nicole Maskiell’s discussion of connections among enslaved people in the region. See Bound by Bondage, ch. 7. Indeed, we can responsibly imagine the various relationships Caesar had among enslaved and free black people in the Valley by considering the following sources, which only begin to scratch the surface of the clues available within extant Dutch family and church records. In 1785, Theunis Van Vechten of Catskill left his wife Judith “during such time she continues my widow a negro woman slave such as she chuise of those which I die possessed of.” Theunis was Dirck van Vechten’s great-uncle, whom Dirck must have known during his boyhood in Catskill. Theunis’s brother, another Dirck, was Dirck van Vechten’s paternal grandfather. In the will, Theunis leaves land to a son that was “conveyed to me by my brother Dirck van Vechten and his son Hubertus Van Vechten [in the nearby area once called Loonenburg].” It seems likely that Hubertus, Dirck’s father, sold that Loonenburg land once he decided to move permanently to Tryon County, the place from where Caesar escaped in December 1782. Did Caesar have kin among the slaves that Theunis was “possessed of”? This branch of the Van Vechten family clearly circulated both enslaved people and land amongst each other. What I am suggesting here, in line with Maskiell, is that Caesar likely made use of his own network of associations and geographical maps when he took flight. Wills, Volume 38, 1785-1786, New York County Surrogate’s Office, 43-47.

[12] Dirick van Vechten, 1790 Federal Census, Mohawk, Montgomery County, New York.