Cécile was born in colonial Saint-Domingue in the early 1770s, on the cusp of what would later become known as the ‘age of revolutions.’[1] She lived a life that was shaped by those political, military, and social upheavals. In 1793, two years after the beginning of the Haitian Revolution and at the very moment that abolition was being instituted in the colony, Cécile was forced to board a ship to join her enslaver’s household in Maryland.[2] Two years later she escaped with sailor-turned-gardener Pierre La Fitte. They left the plantation early on a Saturday morning, taking with them a handful of their enslavers’ silver cutlery to pay their way as they sought passage overseas. Removed from the place of her birth, Cécile sought her freedom in the maritime mobility of the revolutionary Atlantic world.

Cécile was born in the Artibonite region of what is now Haiti, possibly on a coffee plantation in the western mountains, to a young woman named Marianne. Three years later she was joined by a sister, when Marianne gave birth to a second daughter named Souris.[3] We know little about their early life together, but we know it was shaped by the rhythms of the communities of people with whom they lived. Cécile grew up in a world that was predominantly African, hearing the adults around her speak multiple African languages as well as Kreyol and French, and learning the cultural and religious practices which they maintained and adapted to fit their needs in the colony.[4] She also grew up in a world that was ruled by the unrelenting rhythms of the plantation labor regime, in which violence was quotidian and survival was inextricable from dissimulation, subversion, and resistance. Cécile learned at a young age how to survive in that system as best she could.

Cécile, Souris, and Marianne had not seen their enslaver, Etienne, for several years by the time he ‘sent’ for them to join him in Maryland in 1793, as Etienne had lived in Touraine in central France with his mother and siblings since earlier in the decade, before moving to Maryland.[5] In those years, however, a lot had changed. Saint-Domingue was becoming more politically unstable, as the free population warred over questions of independence and civil rights. Cécile likely heard news and rumors of conspiracies, political machinations, and events occurring in the French metropole. In Fall 1791, news reached the Artibonite of a massive uprising on the plantations near the northern city of Cap-Français. Over the next two years, Black revolutionaries established themselves as a serious military and political force in the colony. As the revolutionaries fought French forces, and France went to war with Britain and Spain, the Artibonite became a battleground, and by the fall of 1793, Spanish, British, and French troops controlled much of the region.[6] Cécile also heard news of abolition: French authorities had begun to abolish slavery, beginning in the north and spreading to the West and South in October 1793.[7] It was in this context, simultaneously unstable and ripe with emancipatory possibility, that their enslaver’s agents forced the three women to travel from the plantation in the western mountains to the port town of St. Marc, and boarded them on a ship bound for Maryland.

Cécile traveled to Maryland with her sister and her mother, a small family taken out of a wider community. She certainly left behind family and friends, although we cannot know who these people were. On the ship, the three women met eight others who had been ‘sent’ for by their enslaver’s family, who formed similar fragmented groups.[8] The eleven people arrived at L’Hermitage plantation in Frederick County, Maryland, just as the winter was setting in. In Maryland, Cécile found herself in very different circumstances to those in which she had grown up. The chilly, rolling fields of Frederick County were a stark contrast to the tropical mountains of Saint-Domingue. She was now one member of a small group of displaced Black Francophone individuals, brought together by circumstance and language but isolated in the new land in which they now lived. Cécile navigated not only new languages and foreign geographies, but the surveillance of her enslaver and his family on the plantation.

When a White sailor named Pierre arrived at L’Hermitage to work as a gardener, he may have stood out to Cécile. Unlike most other seasonal laborers on the plantation, he spoke French, and the two could have communicated easily. Still fashioning himself in sailor’s clothes, he may have told stories of his time on a French privateering ship, seizing foreign prizes and traveling from port to port. We do not know whether it was Cécile or Pierre who suggested the plan to escape. Perhaps Cécile had pressed him to act as her accomplice from the start of their relationship. Perhaps Pierre had promised her he could get her passage back to post-emancipation Saint-Domingue, or take her to a place where she might be able to live as if she were free.[9] Either way, the plan was set. In the cold of an early February morning, Cécile and Pierre seized a handful of silver cutlery from Etienne’s house and left L’Hermitage for Frederick, where they sold some to a silversmith willing to look the other way. Where they went is not clear, although Etienne clearly suspected them of seeking passage overseas.

Cécile took a huge risk in claiming her freedom with her feet. Even if she was not recaptured by her enslaver, the revolutionary Atlantic was a vulnerable place to be a young Black woman without proof of legal freedom. It was risky to seek her freedom alongside someone she had not known for very long, a White man whose race and gender afforded him considerable power over her.[10] And by leaving L’Hermitage, she also made the decision to leave behind her mother and sister, the two family members with whom she had remained united. Cécile’s decision to leave in spite of these conditions suggests her desperation, her resolve, and above all, her bravery. Silver spoons in hand, Cécile walked away from L’Hermitage and towards the freedom she intended to forge.

View References

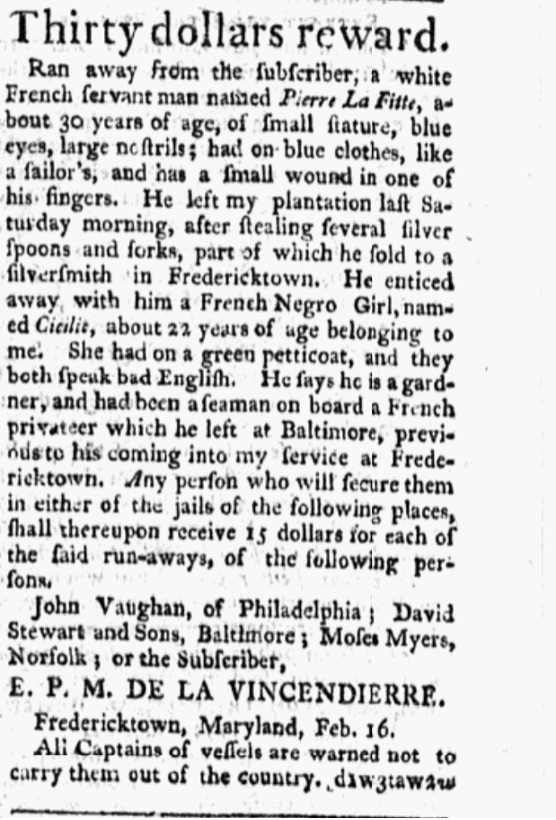

[1] This date range is based on two different documents: the advertisement above, which indicates Cécile was born in 1772 or 3; and the Declaration of Negroes, which gives her age as 18, suggesting she was born in 1775. I have spelled Cécile’s name as it appears in the “Declaration of Negroes” document filed by her enslaver upon her arrival in Maryland, and not as it appears in the advertisement, for the reason that the former suggests a level of formality corresponding to an ‘official’ name. It is possible she was called by both variations on her name. “Thirty Dollars Reward,” Gazette of the United States and Daily Evening Advertiser, February 20, 1795; Frederick County Court (Land Records) Declaration of Negroes, December 28, 1793, Liber WR, folio 775, https://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc5400/sc5496/051900/051919/images/landreclib11fol755.pdf (accessed June 20, 2024).

[2] Frederick County Court (Land Records) Declaration of Negroes.

[3] The La Vincendière family owned multiple coffee and indigo plantations in the Artibonite Valley and surrounding mountains. On a map of the region from 1790, a cluster of land parcels owned by the La Vincendières in the area called Boucan Paul includes one labeled ‘Vincendière fils,’ suggesting it was owned by Etienne Pierre Marie de la Vincendière, Cecile’s enslaver and son of family patriarch Etienne Bellumeau de la Vincendière. “Papiers La Vincendière,” in H. De Branche et al, eds., “Plantations d’Amérique et papiers de famille,” II, Notes d’histoire colonial, 60 (1960), 56-58; Françoise Thésée, Négociants bordelaise et colons de Saint-Domingue, Liaisons d’habitations: La maison Henry Romberg, Bapst et Cie, 1783-1793 (Paris 1972), 44-45; R. Phelipeaux, “Plan du Quartier de l’Artibonite, Isle St. Domingue” (1790), Digital Library of the Caribbean, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00028445/00001 (accessed June 30, 2024).

[4] In 1789, an estimated 60% of the population of French colonial Saint-Domingue was African born. On one plantation which Etienne Sr. purchased in 1786, for example, 85% of the enslaved individuals included in the sale were described as African born. Thésée, Négociants bordelaise, 70.

[5] Sara Rivers-Cofield, “French Refugees and Slave Abuse in Frederick County, Maryland: Jean Payen de Boisneuf and the Vincendière Family at L’Hermitage Plantation,” in Meredith D. Hardy and Kenneth Goodley, eds., French Colonial Archaeology in the Southeast and Caribbean (Gainesville FL, 2011), 33; Thésée, Négociants bordelaise, 70.

[6] David Patrick Geggus, Slavery, War, and Revolution: The British Occupation of Saint-Domingue, 1793-1798 (Oxford, 1982),109.

[7] Carolyn Fick, The Making of Haiti: The Saint-Domingue Revolution from Below (Knoxville TN, 1990), 166.

[8] In addition to Cécile, Souris, and Marianne, those groups were: François Acajou, Jean Sans-nom, Veronique, and Maurice, all ‘sent’ for by Marguerite Elisabeth Magnan de la Vincendière; Pierre Louis, Lambert, and Fillette, ‘sent’ to Jean Payen de Boisneuf; and Saint-Louis, ‘sent’ to Victoire Vincendière. Frederick County Court (Land Records) Declaration of Negroes.

[9] By 1795, slavery had been abolished by the French National Convention.

[10] It was not uncommon for Black travelers, either those who were legally free or passing as free, to be accused of being enslaved and claimed as such by white acquaintances. See, for example, the case of Etienne, a free Black man who was claimed as a slave by a white traveling companion after a voyage from Guadeloupe to Philadelphia in 1803, described in Isaac Hopper, “Tales of Oppression. No. XVIII,” National Anti-slavery Standard (New York, April 22, 1841); Acting Committee Minutes, 1798-1810, 194. AmS 042, Series 1, Pennsylvania Abolition Society Papers, Collection 0490 (PAS Papers), Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia (HSP). For a case involving a young woman traveling with a white man, see the case of Rebekah, a free woman of color who left Charleston S.C. with a white British military officer for Jamaica. When he left her there, she found work as a domestic laborer in a French household. She traveled with them to Saint-Domingue, where they sold her in spite of her insistence that she was free. Pennsylvania Abolition Society Acting Committee Papers, 1789-1797, 415. AmS 0412, Series 1, PAS Papers, HSP.