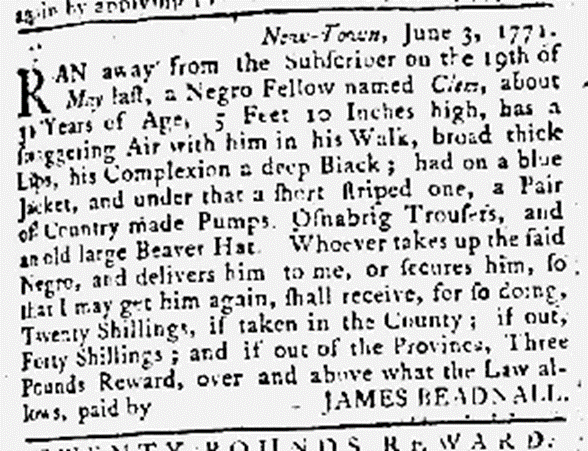

During the Age of the American Revolution, an enslaved man named Clem left his enslaver, a Catholic priest and a papist patriot, and protested slavery with his feet. Like other bound people in the Chesapeake, he left in the summer, as the weather improved. Determined to own himself, if merely for a brief period of time, the thirty-one-old-year man stole not only himself, but also the clothes that had been bought for him by his enslaver. With them, he would pass for free. Using the veil of night to disguise himself, the ”Negro Fellow” concealed his escape. His “Complexion,” James Beadnall explained, was “a deep Black.” For two weeks, if not longer, he remained at large; he eluded the judgement of the man of the cloth.[1]

Like many enslavers, the preacher turn patriot afforded the fugitive time to return of his own volition. Perhaps, he might have reasoned, the enslaved man took time to visit his family. If not to reunite with his wife or children, Clem might have left his owner to reconnect with friends who toiled elsewhere—perhaps on a nearby plantation. The enslaved man’s reasons notwithstanding, Father Beadnall did not wait long before reporting him missing. His solicitation of his neighbors’ help suggests that the man might have had a chance of securing his freedom. With that thought foremost in his mind, the New Town resident offered large rewards to his would-be deputies. If apprehended in the county, Beadnall promised his marshal “Twenty Shillings,” in addition to what “the Laws allows.” If captured outside the county, he doubled the prize. If Clem managed to make his way beyond the boundaries of the colony of Maryland, he offered his bounty hunters even more: “Three Pounds.”

In either case, Beadnall seemed fully aware of the fact that returning Clem to slavery would not be easy. Undaunted, he warned the readers of Anne Catherine Green’s Maryland Gazette, that capturing the fugitive might prove a challenge. For in addition to the clothes he carried with him, in addition to stealing away himself, the minister reported, the freedom seeker clearly thought highly of himself. Despite the brute politics of slavery, that left many enslaved African Americans fearful and humble in their demeanor, the Maryland fugitive walked up. Implicitly, the preacher advised caution in the apprehension of his property. Clem would not easily yield. He would not passively comply. Quite the contrary. Beadnall provided his enterprising neighbors with what amounted to very useful information: “In his Walk,” Clem’s master made plain, he “has a swaggering Air with him.” In walking in his own unique, stylized manner, the daring man declared himself his own person.

During an era in which early Americans were starting to declare themselves free of the tyranny of their King and likewise the Parliament of Great Britain, Clem proclaimed himself subject to no-one. In a not-so-subtle way, he challenged not only his enslaver’s authority, but also anyone else who would deny him a sense of personhood or somebodyness. Well before he had even absconded, the African American man walked a walk of a person who clearly thought himself free.[2]

In the end, Clem’s strut registered one of many ways in which people of African descent achieved resistance, agency, and humanity before emancipation. In seeking freedom, he resisted slavery. As colonial Americans of European descent began imagining themselves slaves of their King, the enslaved man’s “swagger” documented his disdain for any form of oppression. As to the subject of the American Revolution, one can only imagine what he made of it all. One thing, however, was for certain. Clem would not be denied his freedom any longer.[3] In walking in style, he might have convinced others that he might have indeed owned himself. He might have made his would-be bounty hunters hesitate and consider seriously the precarious nature of the business they were engaging. Without question, by walking in the way he had, Clem told the world he was somebody. That he was a force to be reckoned with. Unafraid and fearlessly, he walked into history and snatched for himself the laurel of authorship.[4]

View References

[1] Maura Jane Farrelly, Papist Patriots: The Making of an American Catholic Identity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 167-168.

[2] Posture and the way an individual carried themselves signified at once personal control, power, and agency. Among the gentry, body language communicated style, etiquette, and status, both real and imagined. Richard L. Bushman, The Refinement of America: Persons, Houses, Cities (New York: Knopf, 1992), pp. 64-66; Shane White and Graham White, “Reading the Slave Body: Demeanor, Gesture, and African-American Culture” in Bruce Clayton and John Salmond, eds., Varieties of Southern History: New Essays on a Region and Its People (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1996), pp. 41-61

[3] The contradictions of the language of the American Revolution could not have escaped the attention of enslaved African Americans. See F. Nwabueze Okoye, “Chattel Slavery as the Nightmare of the American Revolutionaries” William and Mary Quarterly 37.1 (January 1980): 3-28.

[4] For a fuller account of enslaved African Americans expressing resistance and agency viz-a-viz body language, see my “Pretty, Sassy, Cool: Slave Resistance, Agency, and Culture in Eighteenth-Century New England” New England Quarterly 89. 3 (September 2016):457-481. For a fuller account of the ways in which enslaved African Americans have co-signed or co-authored runaway slave advertisements, see my “’Indubitable signs’: Reading Silence as Text in New England Runaway Slave Advertisements” Slavery & Abolition 42.2 (2021): 240-268.