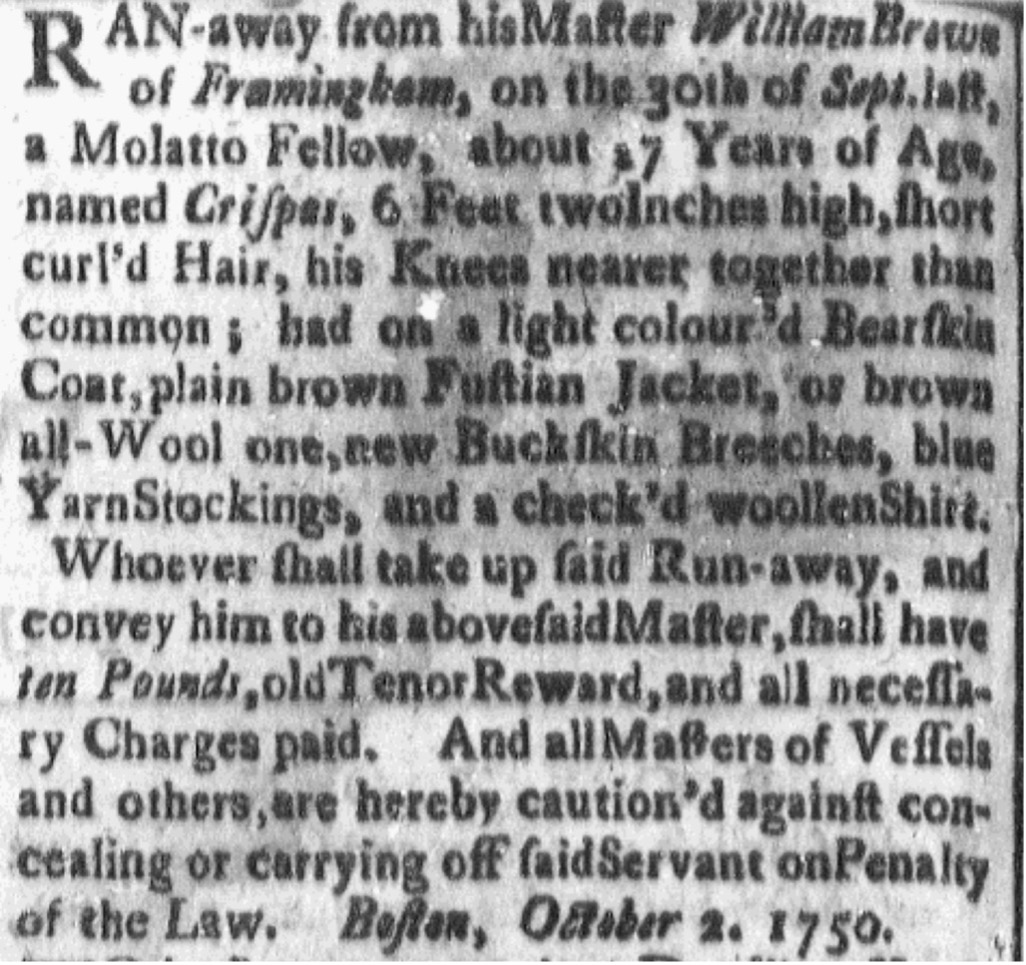

Crispas was an imposing figure of a man, more than six inches taller than the average White American men of his time.[1] He came from Framingham, some twenty miles west of Boston, and a community of fewer than two hundred households and around one thousand residents. Crispas needed to get away if he was to secure his freedom. Almost fifty days after his escape, the third and final publication of a slightly amended version of William Brown’s advertisement suggested that Crispas had succeeded.[2] It would be two decades before Crispas again appeared in local newspapers. Initially he was identified as Michael Johnson, which may have been the name that Crispas had assumed following his escape. If so, he had not completely abandoned his original identity, for a few days later on March 12, 1770, the Boston Gazette identified him as “A mulatto man, named Crispus Attucks, who was born in Framingham.”[3]

Readily identifiable by his height and color, Attucks had helped lead a crowd of Bostonians protesting against British soldiers in the heart of Boston. When the soldiers opened fire, Attucks was one of five killed in what became known as the Boston Massacre, and one of the first to fall in the struggle against Britain. It is impossible to be absolutely certain that Crispas and Crispus Attucks were one and the same. However, his very unusual name, his striking height, his origins in Framingham, and his “mulatto” identity all appear to make this highly likely.

Who was this man, and what had he become in freedom? There is evidence that even while enslaved Crispas, as he then was, had occasionally worked as a sailor on short coastal voyages. This might explain his decision to seek freedom in a life at sea, and many of the accounts recorded immediately after the Boston Massacre identified him as a seafarer working on deep water ships, including whalers. James Bailey, a sailor who gave evidence at the Boston Massacre trial, recalled seeing Attucks “at the head of twenty or thirty sailors,” while another witness identified Attucks as one of “twelve sailors with clubs” at the front of the crowd harassing the British soldiers.[4] As a self-liberated seafarer, Crispus Attucks would have worked alongside Indigenous, Black, White, mixed-race and other seafarers in one of the most racially and ethnically diverse workforces of its time. Perhaps as much as one-fifth of late-eighteenth century New England seafarers were Indigenous, Black, or mixed race.[5]

While many people today regard Crispus Attucks as the first African American to die for the Patriot cause, contemporaries had a more nuanced understanding of his racial identity. The record of the trial of the British soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre, as well as the publication of testimony of more than one hundred Bostonians, reveal that Attucks was rarely identified as a “Negro,” or as a Black man.” Instead, he was described as “mulatto” or “molatto,” and sometimes even as an “Indian.”[6] Perhaps he was a descendant of John Attuck, an Indigenous man executed in 1676 for his alleged role in King Philip’s War, and if so he may have been the son of an African man and a Wampanoag woman, both of whom were likely enslaved. Such relationships were not unusual, and New England was home to a significant number of enslaved people of mixed Indigenous and African heritage. What is clear is that people named Attuck, or with similar names, can be found in Natick and Framingham around the time of Crispus’s birth, including an Indigenous woman Nancy Peter Attuck who married an African man Prince Yonger, Jacob Peterattucks, and Hannah Katuck.[7]

From birth until the age of about twenty-seven, Crispus Attucks had lived as an enslaved man in rural Massachusetts. But following his self-liberation he spent twenty years—the majority of his adult life—as a sailor; his large, powerful, and commanding presence, was that of a man who had grown used to freedom. His actions in the moments before he was killed showed him as such. Andrew, an enslaved man who witnessed the events, described Attucks as taking the lead, for he “threw himself in, and made a blow at the officer…then [he] turned round, and struck the Grenadier’s gun at the Captain’s right hand, and immediately fell in with his club, and knocked his gun away, and struck him over the head, the blow came either on the soldier’s cheek or hat.” Attucks took hold of the soldier’s “bayonet with his left hand, and twitched it and cried, ‘kill the dogs, knock them over’,” a cry taken up by the crowd behind him. In his closing statement in defense of the soldiers at their trial John Adams described the angry crowd as being “under the command” of Attucks, “whose very looks was enough to terrify any person… He had hardiness enough to fall in upon them, [the soldiers] and with one hand took hold of a bayonet, and with the other knocked the man down.” Perhaps he was motivated by the ideology of the Patriot cause, or maybe driven by the anger of working Bostonians and sailors who resented the British soldiers and their actions. Either way, Crispus Attucks had been born into slavery, but he died a strong and determined free man.[8]

View References

[1] Continental Army records indicated that White soldiers had a mean height of 68.1 inches (just under 5 feet 7 inches). See Kenneth L. Sokoloff and Georgia C. Villaflor, “The Early Achievement of Modern Stature in America,” Social Science History, 6 (1982), 457-9.

[2] William Barry, A History of Framingham, Massachusetts, Including the Plantation, From 1640 to the Present Time (Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1847), 62.

[3] “BOSTON, March 12,” Boston Gazette (Boston), March 12, 1770. For the various articles identifying Michael Johnson/Crispus Attucks, see J.L. Bell, “On the Trail of Crispus Attucks: Investigating a Victim of the Boston Massacre,” Readex Report: A biannual publication offering insights into the use of digital historical collections, 4 (February 2009), https://www.readex.com/readex-report/issues/volume-4-issue-1/trail-crispus-attucks-investigating-victim-boston-massacre [accessed December 12, 2024].

[4] The Trial of William Wemms, James Hartegan, William M’Cauley, Hugh White, Matthew Killroy, William Warren, John Carrol, and Hugh Montgomery, Soldiers in his Majesty’s 29th Regiment of Foot, For the Murder of Crispus Attucks, Samuel Gray, Samuel Maverick, James Caldwell, and Patrick Carr (Boston: J. Fleming, 1770); A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre in Boston, Perpetrated In the Evening of the Fifth Day of March, 1770… (Boston: Edes and Gill, and T. and J. Fleet, 1770), 176, 174.

[5] W. Jeffrey Bolster, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1997), 5-7, 26-8.

[6] The Trial of William Wemms.

[7] J.H. Temple, History of Framingham, Massachusetts. Early Known as Danforth’s Farms, 1640-1880 (Framingham: Town of Framingham, 1887), 254-5. The people with the name Attuck (or similar, and with variable spellings) are listed in Bill, Belton, “The Indian Heritage of Crispus Attucks,” Negro History Bulletin, 35 (1972), 151. For more on mixed race enslaved people in New England, see for example Jared Ross Hardesty, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019), 101-2, 122-3.

[8]The Trial of William Wemms, 114, 176.