Crispin fled enslavement and successfully established his freedom. Moreover, while still enslaved, he boldly indicated his politics by the clothing he wore, clearly sympathizing with the Black revolutionaries on St. Domingue (later Haiti) who fought and died to abolish racial bondage on the island. After making his way from Philadelphia to St. Domingue, Crispin enjoyed the protection of authorities on the island from being returned to bondage. Crispin’s story had a happy ending, even though he had to risk everything to establish his personal liberty.

Crispin first ran away in April 1793, about a year after having been purchased and forced to move to Philadelphia by Stephen Girard, a merchant and one of the richest men in the United States. Like many enslavers, Girard was incensed that Crispin would dare to seek his freedom. He ran an initial newspaper advertisement dozens of times, much more frequently than was common at the time.[1] Girard’s strategy worked, and Crispin was recaptured and returned to slavery within a year. Afterward, Girard’s brother wrote him a note of congratulations, noting that capturing an escaped slave “is the sweetest vengeance.”[2]

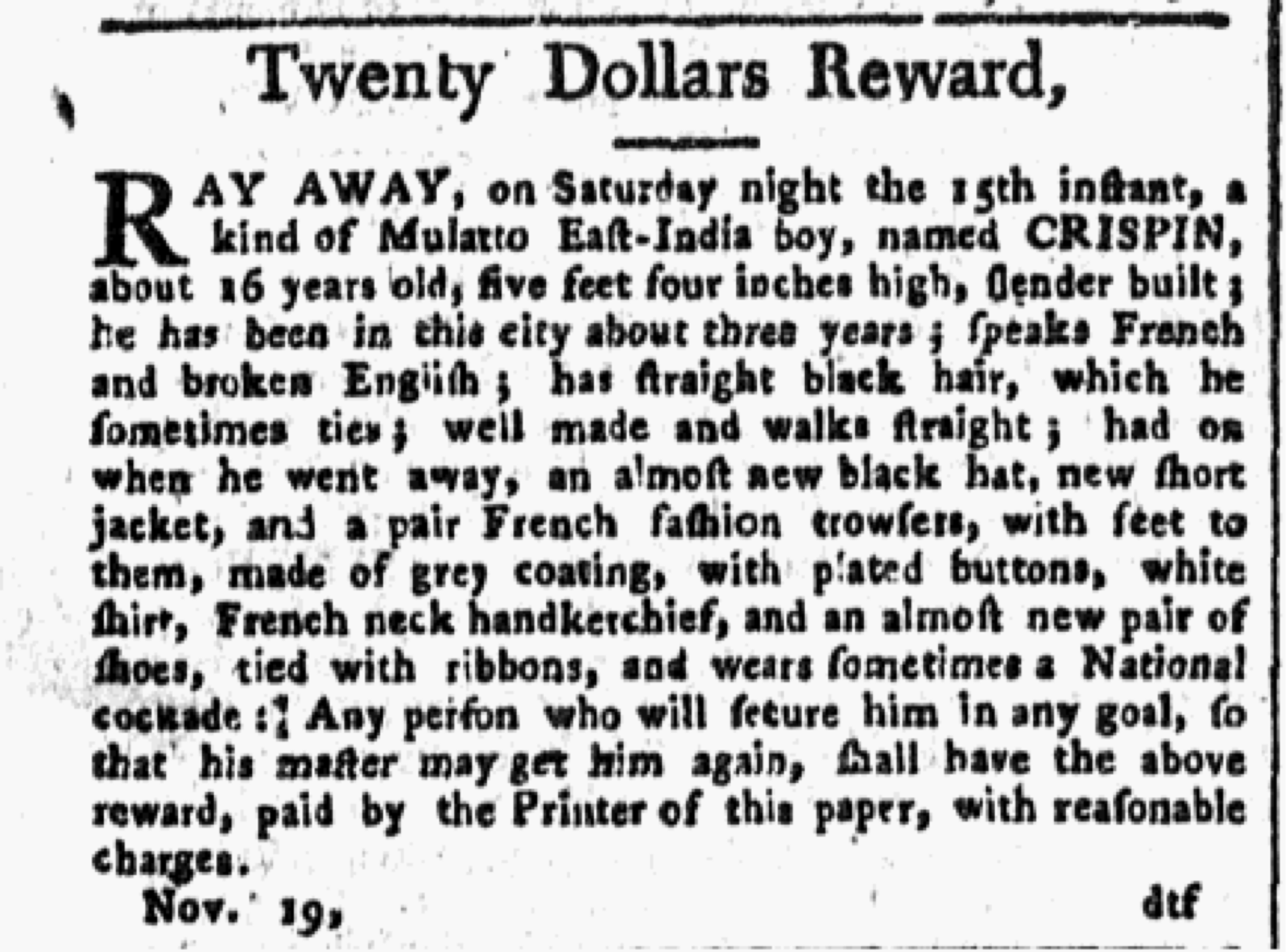

Crispin fled a second time in November 1794, as recorded in the advertisement above. Girard was livid. He paid for a new advertisement to run seventy-five times, and wrote fifty letters to other merchants and friends along the East Coast urging them to be on the lookout for Crispin and to place similar notices in their local newspapers. He hired agents in Williamsburg, Virginia and New York City to track down Crispin. Girard wrote that he would spare no expense to capture the 16-year-old who he claimed as his human property. This time Girard failed to get his “vengeance,” and Crispin succeeded in gaining his permanent freedom.

Before he took flight in 1794, Crispin was able to acquire and wear clothes that reflected his identification with revolutionaries in both France and St. Domingue. Crispin thus directly challenged the man who claimed to own him—perhaps one of his many actions that enraged Girard. As detailed in the newspaper notice reproduced above, Crispin wore a “National cockade,” “French fashion trousers,” and a “French handkerchief.” These were all symbols of ideals of liberty and equality associated with Revolutionary struggles for freedom at the time, from North America, to St. Domingue, to France in the late eighteenth century. When he fled a second time, Crispin was able to fulfill his own desires to be a free person.[3]

Crispin was multi-racial, born of a slave mother and most likely a father from the Indian subcontinent. He grew up on one of the Caribbean Islands colonized by France. In Philadelphia, he may well have socialized with many of the slaves of white planters who had fled the revolution in St. Domingue and settled in Philadelphia. He used the knowledge acquired from other Black Philadelphians to plan his escape. Likely with the assistance of a free Black sailor, he secreted himself on board a ship heading from Philadelphia to St. Domingue and freedom. Or perhaps he signed on as a ship’s sailor.

When Girard learned that Crispin had made it to St. Domingue, he contacted an agent there to demand him to return the freedom seeker. Crispin resolutely refused, preferring to enjoy his liberty. When Girard asked French General Laveaux, the governor of St. Domingue, to force Crispin to return to Philadelphia, he received a scathing reply:

“You must know very little of me to dare to hope that in defiance of our Glorious Constitution, I would consent to force a man against his own will to leave the land of liberty where he has taken refuge. No, Citizen, I cannot do what you ask of me–arrest the Citizen Crispin. In coming to Port de Paix he has come to enjoy liberty. In Philadelphia he was a slave. Have I the right to order him to take up his chains again? Assuredly not. I cannot break the laws, especially the one relating to liberty.”[4]

Crispin obviously shared General Laveaux’s commitment to freedom. The Revolutions that swept the Atlantic World in the decades after the American Revolution spread the ideal of liberty and provided opportunities for men like Crispin to establish his own.

View References

[1] “Ran Away Last Sunday night . . . Crispin,” The Federal Gazette and Philadelphia Daily Advertiser, April 16, 1793.

[2] John Girard to Stephen Girard, Jan. 1, 1794, Stephen Girard Papers, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia.

[3] On French Revolutionary Fashion, see the images and information in the online Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibit, https://unframed.lacma.org/2016/08/03/french-revolutionary-fashion

[4] Sept 19, 1795, Letter Received #356, Stephen Girard Papers, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia; words translated from French and modernized.