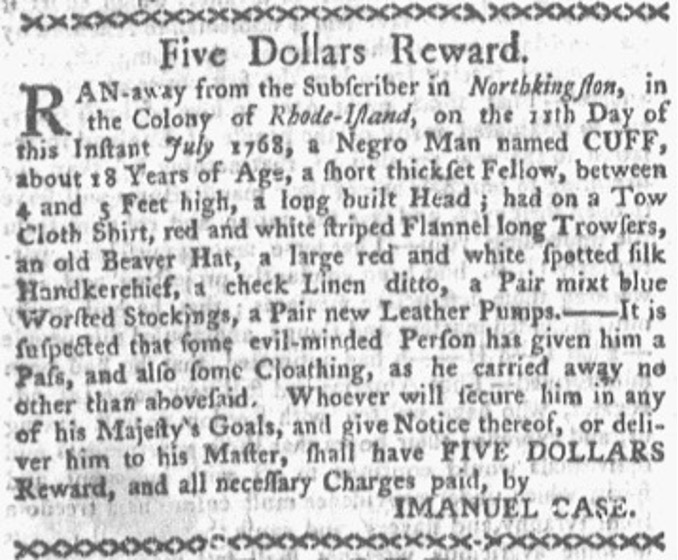

Cuff was eighteen when he escaped from one of the wealthier men in North Kingston, a small town across Narragansett Bay from Newport. It was early July 1768, and in the warm summer weather Cuff left with only the clothes he was wearing. Immanuel Case advertised for Cuff in the local Newport Mercury on July 11 and again in the Boston Gazette on August 1, suggesting that Cuff remained at liberty and that Case feared the young man had already made his way as far as Boston, some seventy miles to the north.

The Rhode Island census of 1774 recorded Immanuel Case as the head of a household of seven people in South Kingstown, including himself and his wife, their children (a boy and a girl), and three Black people who most likely were enslaved. Case was a wealthy innkeeper in Tower Hill, South Kingstown, and his tavern was popular with travelers, including Benjamin Franklin.[1] He also ran a store and regularly advertised a wide variety of textiles, paper, metal goods, as well as rum, sugar, tea and the like, and he held property all over the county. A leading member of his community, Case was a deputy in the Rhode Island assembly in 1776 and 1777, then an Assistant in 1778, while also serving as a Justice of the Peace. It seems likely that the enslaved people in his household worked in his inn, his store, and in his home, and perhaps on his land.[2]

Case’s advertisement in the Boston Gazette includes the somewhat unusual suggestion that “some evil-minded Person has given him a Pass.” In 1704 the Rhode Island assembly had legislated against the free movement of enslaved Africans and indigenous people “without a Certificate from their Masters, or some other English Person of the Family to the which he, she, or they belong.” The law specified that any Black person found without a pass should be taken into custody and brought before a state official, who could then “cause said Negro or Negroes, Indian or Indians, to be Publickly Whipt at the Public Whipping Post of such Town where such Offence shall be Committed, not exceeding fifteen Stripes, unless their incorrigible behaviour deserve more.” Furthermore, any White person who chose to “Entertain any Slave” without the enslaver’s consent was to be fined. Just over a decade later “An Act, to Prevent Slaves from Running away from their Masters” recognized that some freedom seekers had escaped “under pretence of being employed in their [enslavers’] service.” The assembly men responded by forbidding ferry-men and boat-men from transporting “any Slave or Slaves… without a Certificate under the Hand of their respective Master or Mistress,” threatening any found guilty of such offences with a hefty fine of twenty shillings. These laws, and Case’s reference to the possibility that “some evil-minded Person has given him [Cuff] a Pass,” suggest that there were White, and perhaps free Black people who might aid the escape of enslaved people by forging written passes for them. There are any number of possible reasons for a person to forge a pass for a freedom seeker, from friendship to a willingness to help an enslaved person reunite with a partner or family members, to a desire to employ the freedom seeker (especially in the case of ship captains who were eager for new crew members.[3]

Case’s publication of second advertisement in a Boston newspaper, some three weeks after Cuff had escaped, shows that the enslaver thought the freedom seeker had succeeded in getting well away from North Kingstown, perhaps with a forged pass and the external aid that such a pass suggested. By the time of the first Federal Census in 1790 there were no Black people in Case’s household. Had Cuff succeeded in making good his escape, and had he been aided in his escape by an ally who had forged a simple pass for him? We cannot know, for with the second advertisement on August 1, 1768, Cuff disappeared from the records.[4]

View References

[1] Entry for Immanel Case, South Kingstown, Rhode Island in Census of the Inhabitants of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Taken By Order of the General Assembly, In The Year 1774, arranged by John Bartlett, (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1858), 85; reference to Franklin and Case’s tavern in William Davis Miller, The Narragansett Planters (Worcester, Mass.: American Antiquarian Society, 1934), footnote 1, 106.

[2] “A new and fresh Assortment of English and India GOODS… By Imanuel Case,” The Newport Mercury (Newport), july 6, July 27, August 3, 1767; “Imanuel Case, On Little-Rest-Hill, South Kingstown, Has just received a fine Assortment of English and India Goods,” The Newport Mercury (Newport), August 26, 1771; John Russell Bartlett, ed., Records of the State of Rhode Island And Providence Plantations in New England, 1776 to 1779, Volume VIII (Providence: Cooke, Jackson & Co., 1863), 4, 218, 386, 220.

[3] “AN ACT Prohibiting Negroes and Indians from being abroad… and for Punishing those that shall Entertain them contrary thereto” (1704), and “AN ACT, to Prevent Slaves from Running away from their Masters, &c.,” (1714), n Acts and Laws of His Majesties Colony of Rhode-Island, And Providence-Plantations in America (Boston: John Allen, 1779), 52, 70-1.

[4] Entry for Imanuel Case, North Kingstown, Rhode Island, in Heads of Families At the First Census of the United States in the Year 1790. Rhode Island (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907), 44.