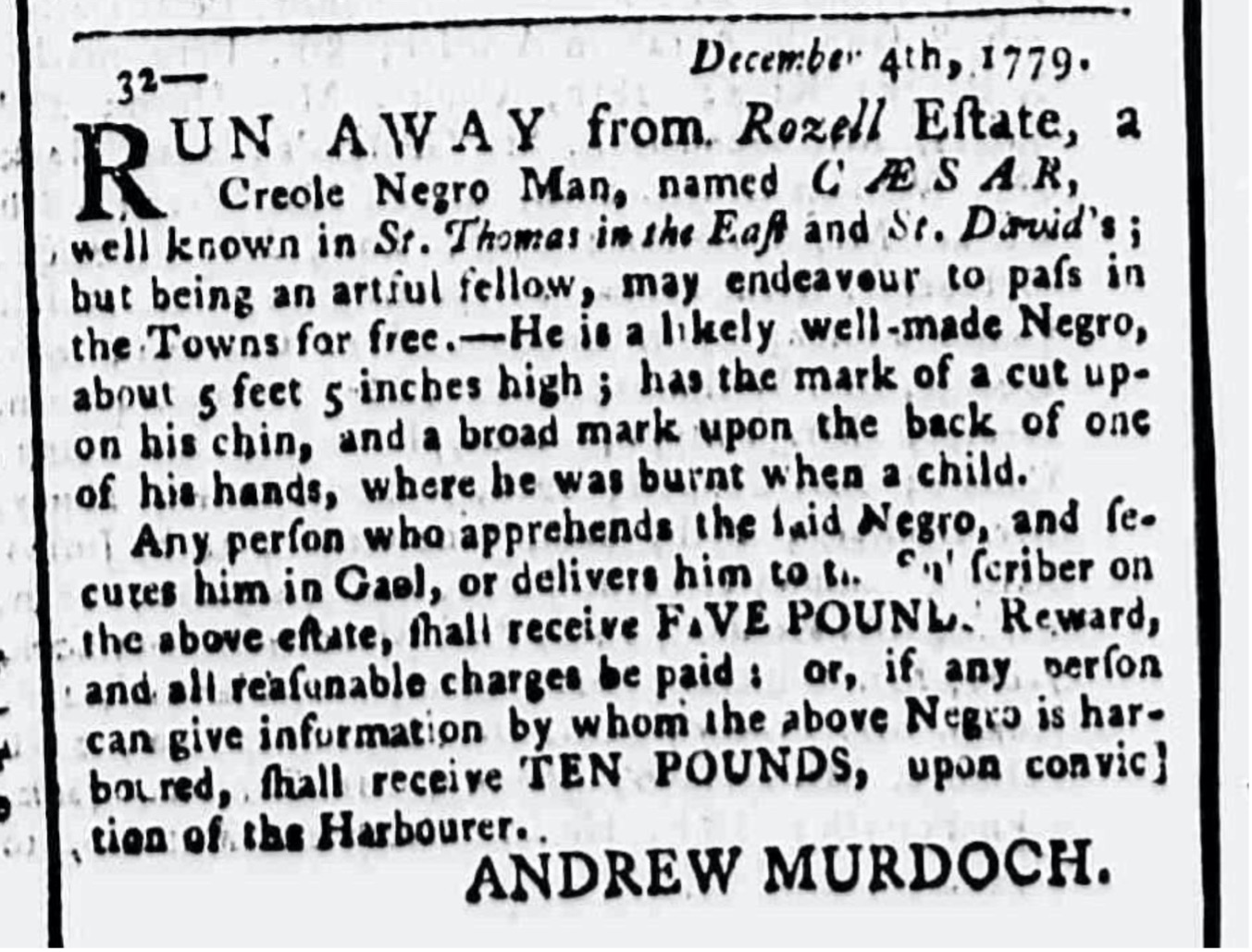

It was a typical advertisement.[1] Caesar had escaped from the Roselle estate, which lay about five miles west of Morant Bay near Jamaica’s south-east coast. Andrew Murdoch, overseer at Roselle, described Caesar as an “artful” man and suggested that he might make his way to a town and attempt to pass as free. Caesar had almost certainly been born on the Roselle estate, and his mother was quite likely an enslaved woman named Fortuna who was still alive when he escaped. He worked with the estate’s horses and was identified in various estate records as a “doctor” who ministered to people and horses alike. Within about two weeks of Murdoch’s advertisement appearing in the Jamaica Mercury, Caesar was taken up at the Aeolus Valley Estate, about four miles north-west of Rozelle, but he escaped again just over a week after he had been returned to Murdoch.[2] And it was then that Caesar’s adventures really began.

In August 1780, eight months after his initial escape, Caesar’s name appeared in an article in the Royal Gazette about a “gang of run-away Negroes of above 40 men, and about 18 women.” Hidden in the dense forests of Four Mile Wood in St. David’s Parish (which lay between Roselle and Kingston), the group were led by Bristol, also known as Three Fingered Jack. This first newspaper story identified only one other member, namely “CAESAR, who belongs to Rozel estate, [and] is their next officer.”[3] Accused of murder, theft, and other crimes, Three Fingered Jack’s group featured in the island’s newspapers for several months. What appeared as dangerous theft and violence by fugitives must have seemed very different to the members of this group and to enslaved people who were all too aware of the limited options and grave danger faced by fugitives from slavery. Following the capture of the outlaw’s wife in December, Governor John Dalling issued a proclamation offering a reward of £100 for Jack, dead or alive. Within a month a party of Maroons had surprised and killed Jack and brought his severed head to Kingston to claim their reward.[4] Caesar escaped, perhaps his initial identification as Three Fingered Jack’s lieutenant was erroneous: at no point in the many subsequent documents referring to Caesar and his actions is there any mention of his being involved in this notorious gang.

Before Jack was caught and killed, Caesar had boarded a ship bound for England, apparently using the name Augustus Thomson. Jamaican law forbade ship captains from recruiting any but free people, yet ship captains who were desperate for crew sometimes took on able-bodied men without asking too many questions. Thomson arrived in London early in 1781, where he surprised Sir Adam Ferguson, a member of the family who owned Rozelle, by knocking on the door of his townhouse and requesting an audience.[5]

Thomson harbored grievances, and a deep sense of the injustice of the treatment meted out to him, his wife, and his children by Andrew Murdoch, the Roselle overseer. Moreover, he appears to have trusted that Sir Adam would give him justice. In an undated document addressed to Charles Ferguson (Adam’s brother), “Doctor Ceasar” [sic] dictated his story in some nine hundred words, signing the document with a double X, “his mark.” It is unclear if Thomson came to Ferguson’s home with the letter in hand, or if it was dictated after his arrival. “This is to acquaint you,” Thomson begins, “that the falling out between the Overseer and me was as follows,” and he proceeded to lay out a story of violent abuse. Thomson had served the plantation as a skilled man; a 1773 list had indicated that he was the second most valuable person on the entire estate. According to Thomson, Murdoch had left him in charge of the estate because the White men present had insufficient experience, but this had resulted in a disagreement between Thomson and a White carpenter. Murdoch returned and spoke with the carpenter, and without even asking Thomson for his side of the story “screwed my two thumbs together, and put me in the Stocks, after giving me two hundred Lashes.” Thomson complained about this treatment but Murdoch “told me to go about my Business and never Trouble him at all, which I took him to his word.” But then Murdoch took possession of Thomson’s provision grounds, keeping him and his “wife Child, Mother or Sister” from accessing the fresh food on which they depended. All Gentlemen, Thomson asserted, would acknowledge this “to be Very Hard.”[6]

Thomson had then sought external mediation, appealing to John Paterson, the former manager of Roselle who still exercised some oversight of Murdoch and the estate. Paterson reacted by hitting Thomson “in such a manner that I spit blood for three days,” and then shackled him with bilboes, an iron bar connecting cuffs around his ankles and a collar around his neck. When James White (an acquaintance of Paterson) visited Roselle and saw Thomson’s condition, White ordered Murdoch to call a doctor, to which Murdoch responded that “I might dy and be damd.” After receiving some medical attention, Thomson was ordered by Murdoch to begin working in the sugar cane fields. This was both a demotion and an insult to Thomson, “being a thing I was never brought up to,” for “I always was brought up a Doctor & horse farrier and horse Gelder.” The punishments continued: Murdoch “gave my wife & Children three hundred lashes each” for giving him food and drink when he was in the bilboes, and he ordered other enslaved people to take and “eat my Hogs and fowls Goats &c which I thought very hard.” Murdoch still refused to release Thomson from the bilboes, proclaiming that “if I died I should be buried with them.”[7]

And it was then that Thomson had escaped. He ended his dictated letter and chronicle of the injustices he had suffered with the plea “I hope You’ll have mercy upon me for the Overseer & Moody the Carpenter.” The letter was accompanied by a list of the items Murdoch had stolen from Thomson, including plates, dishes, wine glasses, tumblers, a horse, silver shoe buckles, two cloth cloaks, a pair of shoes, 18 goats, and a “Case of Doctor’s Instruments.” Finally, two invoices signed by Murdoch appeared to show debts of £80 and £108 that he owed to Thomson.[8]

It is a remarkable document, revealing an enslaved man’s deep sense of pride and his anger at the injustice he has suffered. There is a stark difference between Thomson’s view of his ill-treatment, and Murdoch’s belief that Thomson’s behavior and crimes “were so flagrant and dangerous to the Community in General, that had he been secured here, he ran the risk of his neck.” What does seem clear is that Murdoch owed Thomson money, and he had an incentive to be rid of the enslaved man. The maintenance of slavery in Jamaica depended upon an extreme level of violence that corrupted White morality and justice. Thomson was so convinced that he was in the right that he was prepared to appeal to the man who enslaved him and his family. Thomson had arrived in London nine years after Lord Mansfield’s ruling had determined that no enslaved people brought to England could be sent back to the plantation colonies against their will. It seems likely that Thomson would have known this, learning it from ship’s crew members or from members of London’s large free Black community. But with his mother, wife, and children still in Jamaica, he appears to have wanted to return and to enjoy as best he could the life he had before being attacked by Murdoch and Moody.[9]

Thomson’s faith in Sir Adam’s sense of justice was misplaced. Having heard Thomson’s appeal, Sir Adam persuaded him to return to Jamaica with a letter to Murdoch. “The immediate occasion of my writing now is the return of a Negro, who calls himself Dr Caesar,” Ferguson wrote. “I found him not unwilling to return,” he went on, “but apprehensive of the punishments he would probably undergo,” and so Ferguson gave Thomson “my word that he should be pardoned for his coming away, and the fault he had committed overlooked.” In this letter Ferguson gives no indication that he accepted or believed any of Thomson’s claims, or indeed that he saw anything wrong with the violent punishments Thomson had described. In the late spring of 1781 Thomson returned to Jamaica aboard HMS Prince George, the ship carrying the Duke of Clarence to the Caribbean. By early June Thomson—now Caesar once again—was back at Roselle, but perhaps not surprisingly he was not allowed to settle back into his old life. This may be in part because Murdoch was clearly incensed by Caesar’s appealing to the Ferguson brothers. Within a few weeks, Murdoch reported, Caesar was “skulking about the Neighbourhood, and so far from repenting of his past faults, has been endeavouring to Hurt the Negros Minds.” Within a year Caesar had absconded again, and was captured by some Maroons but soon escaped.[10]

For the next six years Caesar was listed in the Roselle records as an escapee from bondage, and if recaptured Murdoch hoped that “the Law must have put a speedy period to his Life.”[11] Absenting himself was a wise decision, for Sir Adam had apologized to Murdoch for implying “any neglect” on the overseer’s part. Reporting that he was “a good deal uneasy” about Caesar, Ferguson stated that he had done only what was necessary to get the enslaved man back to Jamaica, and he ended by informing Murdoch “If you think that Man dangerous to be kept on the Estate, or that his Example is like to corrupt the rest, it would be better to get rid of him, than to keep him to do harm.”[12]

Caesar would never again be subject to the authority of Murdoch or the overseers and drivers of the Roselle Estate. It is possible that he once again escaped to London, or at least that is what Murdoch believed and stated in a letter to Sir Adam in February 1783.

I found Caesar was in London, from a letter I detected he had sent his Mother here. if the Villain could be secured, & sent back, it would be a service to the island in General. He getting off twice easily must be an encouragement to other Slaves to make the same attempt. We have lately many instances of it, I believe principally from their being received as Free people on board of Ships of War, without proper examination.[13]

Had Caesar managed to join a ship and return to London? During the American War for Independence Britain had lost control of Dominica, St. Vincent, Grenada, and St. Kitts to the French, and West Florida to the Spanish. Following the British defeat at Yorktown, a large Franco-Spanish military force threatened Jamaica. The Royal Navy lost a great many sailors to tropical diseases as well as combat, and captains who were desperate for men with any seafaring experience were more than willing to recruit Black Jamaicans, free or enslaved. This, together with the lasting chaos brought on by the great hurricane of 1780 all made escape at least a little more practical.[14] If Caesar had returned to Britain, perhaps he was the man identified by that name who was living in Deptford, London when he was convicted of theft in March 1786.

Caesar had proved himself an incredibly resourceful man, and perhaps he had written a letter to his mother that could be deployed to suggest he was abroad, making it easier for him to remain hidden in Jamaica. If so, perhaps he was in the Kingston workhouse in 1789, identified as “CAESAR, alias JOHN THOMAS, a creole of this island, and was to be [transported] some years ago by sentence of the court, to Monsieur McLEUR, Hispaniola, both ears cropt, 5 ft. 5 in. high.” This man was the same height, and the prior sentence and the cropped ears all suggested a long history of escape and resistance. Jamaican law mandated the execution of long-term runaways, or transportation and sale off the island, and each year dozens were sold to enslavers in Cuba, Hispaniola, and the central American mainland: such was the fate of the man named Caesar in the Kingston workhouse in 1789.[15]

Whatever his eventual fate, Dr. Caesar had resisted enslavement and ill-treatment for himself and his family with pride, resourcefulness, and determination. He is one of the very few freedom seekers in the eighteenth century to have left us an account of why he had escaped, albeit one dictated to a transcriber. Dr. Caesar had the courage to look his absentee enslaver in the eye, and challenge him to do the right thing.

View References

[1] For a remarkable frank account of slavery on the Roselle Estate owned by his ancestors see Alex Renton, Blood Legacy: Reckoning With a Family’s Story of Slavery (Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2021). Chapter 7 includes the story of Caesar. I am grateful to Mr. Renton for sharing copies of documents from his family’s archive.

[2] “February 1, 1780. RUN AWAY, from ROZELL Estate… a Creole Negro Man, named CAESAR,” The Royal Gazette (Kingston), Supplement to the Royal Gazette, April 15, 1780. This advertisement mentions Caesar’s capture at Aeolus Valley on December 20, 1779, and his subsequent escape eight days after his return to Rozelle. This advertisement was reprinted regularly between April 15, 1780 and January 27, 1781.

[3] “A gang of run-away Negroes,” Supplement to the Royal Gazette (Kingston), July 29 to August 5, 1780, 458. For more on Three-Fingered Jack and his group, see Benjamin Moseley, A Treatise on Sugar… (Longon: G.G. and J. Robinson, 1799), 173-80; Diana Paton, “The Afterlives of Three-Fingered Jack,” in Brycchan Carey and Peter J. Kitson, eds., Slavery and the Cultures of Abolition: Essays Marking the Bicentennial of the British Abolition Act of 1807 (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2007), 42-63; Frances R. Botkin, Thieving Three-Fingered Jack: Transatlantic Tales of a Jamaican Outland, 1780-2015 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2017); William Earle, Obi; Or, The History of Three-Fingered Jack, ed. Srinivas Aravamudan (Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview, 2005).

[4] “Three fingered Jack continues his depredations,” Supplement to the Royal Gazette (Kingston), November 25 to December 2, 1780, 698; “We are informed, that the wife of Three Fingered JACK has been lately removed… to the Jail,” Supplement to the Royal Gazette (Kingston), December 16 to December 23, 1780, 747; “By the King. A Proclamation… Three-fingered JACK,” Supplement to the Royal Gazette (Kingston), December 30, 1780 to January 6, 1781, 13, repeated Supplement January 6-13, 1781, 29; “We have the pleasure to inform the public, of the death of that daring freebooter Three Fingered Jack,” Supplement to the Royal Gazette (Kingston), January 27 to February 3, 1781, 79.

[5] Thomson’s actions, and the events and correspondence that resulted from them, enable us to learn far more about the man and his experiences, and what had driven him to escape and then seek redress of grievances from the men who owned him and his family.

[6] Doctor Caesar to Charles Fergusson, [sic], undated, in Renton, Blood Legacy, 128-30.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.; “Mr Andrew Murdock [sic] which took away from Doctor Caesar,” in Renton, Blood Legacy, 131.

[9] Ibid.; Andrew Murdoch to Adam Ferguson, April 24, 1781, in Renton, Blood Legacy, 141. Somerset v Stewart (1772), [R. v Knowles, ex parte Somerset] 1 Lofft 1.

[10] Murdoch to Ferguson, June 25, 1781, and Murdoch to Ferguson, May 13, 1782, quoted in Renton, Blood Legacy, 142, 144.

[11] Murdoch to Ferguson, May 13, 1782, quoted in Renton, Blood Legacy, 144.

[12] Ferguson to Murdoch, June 30, 1781, quoted in Renton, Blood Legacy, 143.

[13] Murdoch to Ferguson and WH, February 26, 1783, in Renton, Blood Legacy, 145.

[14] For more on the military situation in Jamaica in the early 1780s see Maria Alessandra Bollettino, Matthew P. Dziennik, and Simon P. Newman, “‘All spirited likely young lands’: free men of colour, the defence of Jamaica, and subjecthood during the American War for Independence,” Slavery and Abolition, 41 (2020), 187-211.

[15] Entry for Caesar in Kingston Workhouse listing, October 3, 1789, reproduced in Douglas B. Chambers, Runaway Slaves in Jamaica (I): Eighteenth-Century (2013), 242, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/aa00021144/00001 [accessed March 13, 2025]; See Ebony Jones, “‘[S]old to Any One Who Would Buy Them’: Convict Transportation and the Intercolonial Slave Trade from Jamaica after 1807,” Journal of Global Slavery, 7 (2022), 103-29.