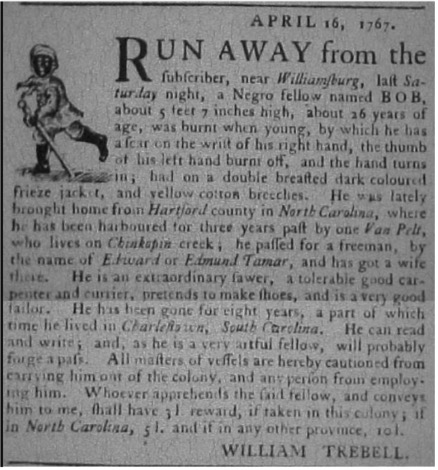

In 1767 Edward Tamar was one of a significant number of enslaved people owned by William Trebell, and Tamar was working for Trebell in the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg.[1] But he was also an enslaved man who had enjoyed a long period of freedom and who had created a life for himself as a free Black man. He was, it appears, determined to be free.

Tamar was most likely born into slavery in Virginia: his various skills and his literacy all suggest that he had been in the colony for most if not all of his life. Trebell’s advertisement casually refers to an injury sustained by Tamar that had scarred his right hand and burnt off the thumb of his left hand, permanently maiming that hand. It seems unlikely that he had been burned as a punishment, for enslaver’s tried to avoid causing permanent damage that adversely affected the ability of enslaved people to work. When he escaped Tamar was living and working in Williamsburg, the capital of colonial Virginia and the heart of the colony’s increasing political activity. Leading figures like Patrick Henry, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson all frequented taverns in Williamsburg to participate in the debate surrounding the liberty and independence: the Raleigh Tavern—”the most famous hostelry in the colonies”—was a hot spot for these political debates.[2]

Despite his injury, Tamar appeared to be an accomplished and talented individual. Trebell described the freedom seeker as “an extraordinary sawer, a tolerable good carpenter and currier, pretends to make shoes, and is a very good tailor.” Trebell clearly understood the extent of Tamar’s talents, and indeed he benefitted from them. While he might have described these attributes in the advertisement solely to provide identifiable characteristics, Trebell’s language implies that he had some respect for Tamar’s skills. On the other hand, Trebell also articulated a negative view of Tamar. For example, Trebell described Tamar as an “artful fellow,” language that warned readers of Tamar’s ability to deceive white people. The contradictory wording within the advertisement may suggest that Tamar and Trebell had a complex relationship. For all that he was aware of Tamar’s skills as a worker, Trebell was well aware that these could prevent his recapture.

William Trebell owned enslaved people who worked both at his plantation and at the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg. It is possible that Tamar had worked on the former, but his skills make it more likely that he had worked in the tavern. Living and working in Williamsburg, Tamar would have been able to communicate and even socialize with other enslaved Black workers, as well as some free Black people. These interactions may have helped inspire him to pursue his freedom, and he also might have received advice on how to stay hidden once he escaped.

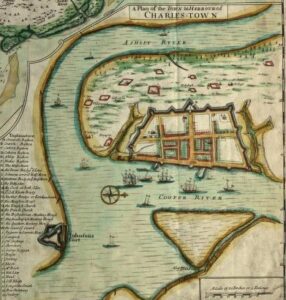

Trebell’s advertisement indicates that Tamar had gone missing eight years earlier, and had only recently been taken up and returned to Williamsburg. This was a remarkably long period of freedom, during which Tamar had passed as a free man, married, and established a new life for himself. He had lived in Charleston, South Carolina for part of those eight years. Perhaps he was one of the freedom seekers in that region who hid in and around the surrounding swamps. One individual, James Matthews, hid in Four Holes Swamp before boarding a ship that took him to freedom in the North. Given his skills and his literacy, Tamar probably passed himself off as free and this may be when he acquired work and experience as a sailor.[3]

Following his time in South Carolina, Tamar was—according to Trebell’s advertisement—harbored by somebody named Van Pelt in Chinkapin Creek in North Carolina. Van Pelt was a sailor during this period according to records, so Tamar could’ve boarded a ship and ended up in North Carolina working as a sailor under Van Pelt.[5] We do not know if Van Pelt knowingly “harboured” Tamar, and he may well have believed the man he employed was legally free. Once in North Carolina, Tamar created a new life for himself, although as a freedom seeker he could never rest easy, and as he found out recapture and reenslavement were constant dangers. The advertisement states that Tamar had “passed for [a] freeman, by the name of Edward or Edmund Tamar, and has got a wife there.” Therefore, it is likely that Tamar spent a significant part of his eight years of freedom in North Carolina. He likely worked as a sailor for at least some of this period. Seafaring was very appealing to freedom seekers because once at sea they were beyond the reach of slave catchers and slaveholders. Additionally, ship captains always needed more sailors, especially those who had some experience, and it was a profession in which Black men could gain employment almost as easily as whites.

Edward Tamar had a powerful desire to reclaim his freedom after enduring the horrors of slavery for a large portion of his life. After eight years of liberty, it is hardly surprising that Tamar was not going to submit to the restraints of slavery without a fight. He had used his years of freedom to make a life for himself, creating a career, marrying, and perhaps having a family.[6] While we know little of Tamar’s life between his escape and his recapture, it is likely that he met his wife in North Carolina or Charleston. Tamar demonstrated the courage and commitment that defined freedom seekers, creating a free life for himself in the middle of the plantation South. We can only hope that Tamar’s commitment to freedom paid off, leading him to spend the rest of his life at liberty.

View References

[1] Koestler, Sally M, “Capt. John Van Pelt & Maria Perrine – Sally’s Family Place,” Sally’s Family Place, Accessed November 10, 2023, https://sallysfamilyplace.com/capt-john-van-pelt-maria-perrine/.

[2] Koestler, Sally M, “Capt. John Van Pelt & Maria Perrine – Sally’s Family Place,” Sally’s Family Place, Accessed November 10, 2023, https://sallysfamilyplace.com/capt-john-van-pelt-maria-perrine

[3] “The Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg,” The William and Mary Quarterly 14, no. 3 (1906): 213–15, https://doi.org/10.2307/1915184.

[4] Crisp, Edw, Thomas Nairne, John Harris, Maurice Mathews, and John Love. A compleat description of the province of Carolina in 3 parts: 1st, the improved part from the surveys of Maurice Mathews & Mr. John Love: 2ly, the west part by Capt. Tho. Nairn: 3ly, a chart of the coast from Virginia to Cape Florida. [London: Edw. Crisp, ?, 1711] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004626926/.

[5]Trifone, Nicole, 2020, “Serious Fun,” Colonial Williamsburg, https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/trend-tradition-magazine/autumn-2020/serious-fun/.

[6] “Swamp used by freedom-seekers recognized on Underground Railroad list,” 2021, Audubon South Carolina, https://sc.audubon.org/news/swamp-used-freedom-seekers-recognized-underground-railroad-list.