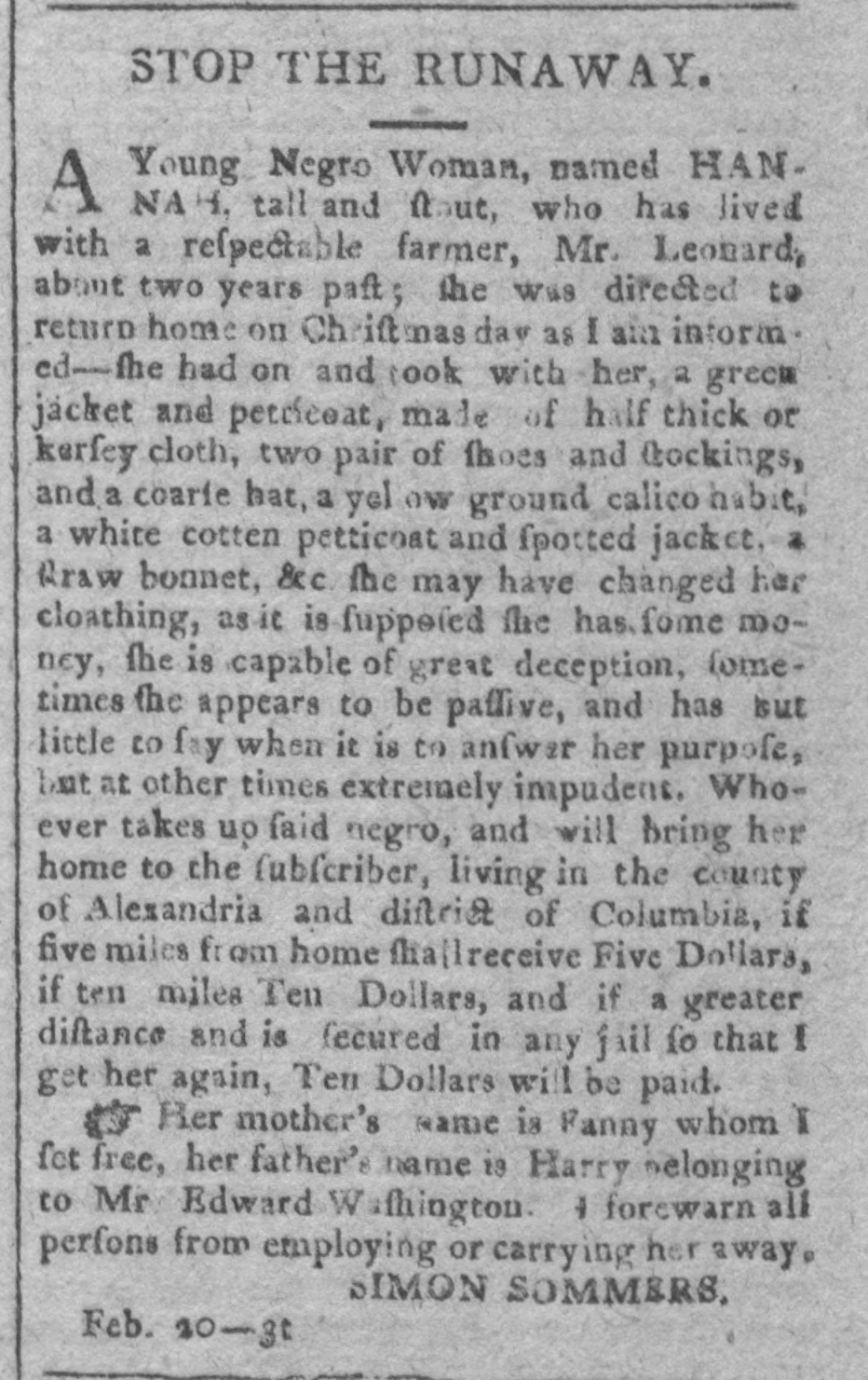

Hannah appears to have escaped somewhere between a Mr. Leonard’s farm and the plantation in Alexandria, Virginia that belonged to her enslaver, Simon Sommers. She had eloped about two months before the publication of this advertisement in early 1805. Mr. Leonard had instructed Hannah to return to Sommers, perhaps because her time working for him had ended, or, perhaps, Sommers wished to grant his enslaved people some time together over the upcoming Christmas holiday. In any case, Hannah disrupted their plans. Hoping to “get her again,” Sommers turned for help in the pages of the National Intelligencer, where he described Hannah as a young woman, “tall” and “strong,” and “capable of great deception,” suggesting there may have been a previous conflict between the two.[1]

This advertisement sheds light not only on Hannah’s escape, but also the strategies employed by the many thousands of North American women who escaped slavery in the Age of Revolutions. Historians have sometimes written of enslaved women’s resistance under slavery being of a more “subtle” character than that of men’s; one noted that “enslaved women ‘played the fool’ more often than men.”[2] Hannah seemed to embrace this strategy; she at times acted, Sommers noted, in a “passive” manner when that was the safest strategy. At other times, she spoke back, prompting Sommers to describe her as “extremely impudent.” To him, this was evidence of Hannah’s “deception,” and it helped explain her escape. Historian Tamika Nunley has further suggested that Hannah’s “display of reticence and discretion” was “not too dissimilar” from the strategies adopted by thousands of other enslaved women of Hannah’s era.[3]

But was there anything “subtle” or “passive” about Hannah’s escape strategy? For one, it appears Hannah rather boldly planned her escape well in advance. Some enslaved people had the luxury of exercising great care in planning their escapes. Others, however, were forced to act on the spur of the moment.[4] Her clothing, for example, suggests that Hannah had prepared for the cold temperatures that were common in northern Virginia in December and January. She packed an extra pair of shoes and wore a thick coat to help her endure the harsh winter. Hannah also carried a small amount of money, indicating that she may have saved as part of her planning. Sommers had “hired” Hannah out, as she was leaving her employment by Mr. Leonard at the time of escape.[5] To earn money, she may have sold vegetables, handmade items, or been given cash gifts.[6]

Hannah also appears to have potentially pre-empted her own manumission through her escape, a very unusual situation. While manumission records show that Sommers planned to manumit at least some of his slaves, including Hannah and her mother, Hannah escaped before her manumission had occurred, proving her strong motivation for freedom, and her apparent disbelief that Sommers would actually free her.[7] Virginia law stated that enslavers had to provide support for the freed slaves, meaning that manumitting slaves was a rather large financial burden on Sommers.[8] Yet, he still attempted to free them, stating that possession of slaves was “Contrary to the spirit of Christianity or humanity…”[9] Attempting to escape enslavement was a dangerous endeavor, often including harsh punishments if recaptured, and perhaps putting her manumission at risk. So, Hannah’s escape further proves how much she yearned to be free.[11]

Timing was also a foundational part of an escape strategy. Hannah escaped enslavement on or around Christmas day. Escapes at Christmas were not unusual because enslavers often had relaxed discipline and work schedules around the holiday, and enslaved people often had permission to leave plantations to visit family and friends. We have evidence of this in narratives published by freedom seekers decades later, and people like Harriet Jacobs, Henry Bibb, and Harriet Tubman all attested to the opportunities the holiday afforded.[11] Hannah most likely was given some time off around the holiday, or at the very least time to travel from Leonard’s farm to Sommer’s plantation, which could have aided her escape.[12]

While we cannot know exactly what Christmas celebrations may have looked like on Sommers or Mr. Leonard’s lands, day-to-day Christmas traditions by enslavers could have offered a time to escape. As referenced in the manumission records, Sommers identified as a Christian and was heavily involved in the Methodist Church.[13] Alexandria County was populated mostly by Anglicans, and often Anglicans celebrated the period of epiphany, between December 25 and January 6th. While enslaved people were usually given only a couple of days off work, enslavers and their families were busy celebrating, so they may have been paying less attention to their enslaved, creating even more opportunities for escape.

Hannah’s strategies appear to have worked, as there was a second advertisement for Hannah published over a year later, on April 10, 1806, in the same newspaper, The National Intelligencer in Washington, DC.[14] The advertisement indicated that Hannah had escaped on Christmas a “year past,” meaning that her bid for freedom had been successful for at least a year. The later advertisement was less detailed: descriptions of clothing a year earlier would have been outdated. However, the reward for her recapture and return to Sommers increased. Not only was Hannah valuable to Sommers, but it was important for him and other enslavers to prove that escape was difficult, dangerous, and usually unsuccessful, to discourage others from escaping. Sommers could have also published this advertisement in the hopes that Hannah was still in the area. The phrase, “she is capable of great deception,” appears in both advertisements, while the line, “sometimes she appears to be passive,” was only in the first, suggesting that what he interpreted as her deceit left the strongest lasting impression.

Between the two advertisements, we can speculate about Hannah’s actions, why she escaped, and what tools she may have used to enable her to find freedom. Hannah was a young woman who was taken from her parents, and sent from farm to farm to work against her will. She, and future generations of her family, were owned entirely by a white man, however committed to the freeing of enslaved people he may have been. Hannah had to develop strategies to survive and escape bondage. She did so by appearing ‘passive’ or ‘deceptive’ at different times to suit her environment, escaping at the promising time of Christmas. What her enslaver interpreted as Hannah’s passive silence or deceitful talking back can also be seen as defensive strategies, and as evidence of a young woman who developed protective strategies using her intelligence and survival skills to escape captivity.

View References

[1] On the other hand, perhaps this language means that Hannah’s escape was unexpected, prompting Sommers to see Hannah as cunning.

[2] Deborah Gray White, “Simple Truths: Antebellum Slavery in Black and White,” in David W. Blight, ed., Passages to Freedom: The Underground Railroad in History and Memory (Washington: The Smithsonian, 2004), 65.

[3] Tamika Nunley, At the Threshold of Liberty: Women, Slavery, & Shifting Identities in Washington, D.C., (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 48.

[4] White, “Simple Truths,” 59. Because of the many contingencies enslaved people faced, they often did not have a choice between planning their escape. Some had the luxury of being able to plan, while others did not.

[5] The practice of hiring out enslaved people was common in the South. Enslaved people were most likely hired out by their enslavers, who negotiated payments and scheduled directly with the hirer. See Dylan C. Penningroth, The Claims of Kinfolk: African American Property and Community in the Nineteenth-Century South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 53.

[6] There is also a possibility that Hannah decided to escape on the spur of the moment. While she had proper clothes and extra money, she may have also had these because she was returning to the Sommers plantation, so she would be carrying all her belongings.

[7] Julia Roberts v. Austin L. Adams & Ann C. Harding Deed of Manumission, in O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family, edited by William G. Thomas III, et al. University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Accessed March 17, 2025, https://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0432.021.

[8] Encyclopedia Virginia, “An Act to Authorize the Manumission of Slaves (1782),” (University of Virginia: Charlottesville, Virginia), Accessed April 6, 2025, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/an-act-to-authorize-the-manumission-of-slaves-1782/.

[9] Julia Roberts v. Austin L Adams.

[10] There are a few possible explanations as to why Hannah chose to escape before she was granted manumission. Potentially, it was simply no longer tolerable to live with Sommers anymore. Or maybe Sommers’s disposition toward manumission made Hannah believe he would not prosecute if she was forced to return. Hannah may have believed that the court might not have allowed manumission for some reason, so she chose to escape when she was presented the opportunity. All of these explanations are speculative but could provide insight into why she may have chosen to flee instead of allowing the court to free her.

[11] Harriet A Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself (Boston: 1861), Accessed via Documenting the South (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill), Accessed April 2, 2025, https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/jacobs/jacobs.html.; Henry Bibb, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, An American Slave, Written by Himself (New York: 1849), Accessed via Documenting the South (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill), Accessed April 2, 2025, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/bibb/bibb.html.; “The Slave Experience of the Holidays,” Documenting the American South (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill), Accessed March 2, 2025, https://docsouth.unc.edu/highlights/holidays.html#:~:text=Some%20slaves%20saw%20Christmas%20as,far%20away%20to%20stop%20them.; Sarah Bradford, Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman (W.J. Moses: Auburn, NY, 1869), 58-60.

[12] The advertisement indicates that Hannah was given permission to be away from Mr. Leonard’s farm around the Christmas period, but we do not know when exactly she escaped or where she was going to. She may have tried to go back to Sommers’s plantation to reunite with her family or to the nearby Washington DC, where there was a small but vibrant free Black community. Hannah’s mother was likely still owned by Sommers, so Hannah could have escaped to travel to find her father, who was enslaved by another man.

[13] Fairfax Resolves Chapter, Sons of the American Revolution, “Simon Sommers,” Fairfax Resolves, accessed April 2, 2025, https://www.fairfaxresolvessar.org/content/ffx_patriotic_patriotgravemarking/simon_sommers.html.

[14] National Intelligencer, Washington DC, April 10, 1806, 4.