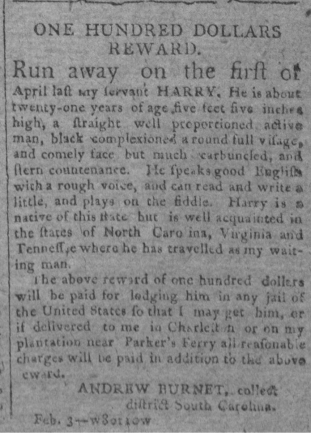

On April 1st, 1803, Harry made his way towards freedom and on December 12, 1803, Andrew Burnet, his enslaver, placed an advertisement in Charleston’s City Gazette seeking his return. Harry was Burnet‘s “waiting man,” an enslaved personal and domestic servant, and a position growing increasingly common in Virginian society. The consistent stream of advertisements offering a one hundred dollar reward for Harry’s capture show how indispensable he was to his enslaver. Perhaps the high price offered was all the more reason for Harry to escape towards freedom.

Harry was possibly chosen as a waiting man because he possessed certain physical qualities. Harry is described as having a “comely face” as well as a “stern countenance.” These descriptors imply that Harry was a good-looking young man, whose seriousness was on display. Historians have noted that an important consideration in enslaving a male domestic was “appearance and deportment.”[1] Enslavers wanted their waiting men’s appearances to reflect their own social superiority and likely sought those who “looked the part.”[2] However as much as Burnet valued appearance he had to settle for the “much carbuncled” nature of Harry’s face. Many people, both Black and White, bore permanent facial scars resulting from diseases and medical conditions. Scarred faces were therefore not unusual, but they did provide enslavers’ advertisements, like this one, with a way of distinguishing freedom seekers, especially when their scars were prominent. The antebellum physician Samuel Gross wrote in 1859 that “the most accurate definition that can be given of a carbuncle is that it is a boil on a large scale.”[3] Gross observed that in London during the late 1850s, “carbuncles” were more common among those of the lower class, who were malnourished and, in the words of Gross, suffered from “mental anxiety.” This may partly explain the particularly “carbuncled” nature of Harry’s face. Might the stressors of being enslaved and mistreatment by his enslavers have caused Harry’s body to express the pain he was in?

Harry’s service to Burnet likely began in his youth, perhaps by assisting Burnet or another enslaver as a personal attendant.[4] This was a common practice for the boys and young men who worked closely with and for their enslavers. William Grimes, a fellow Freedom Seeker, recalled his experience of being trained to perform waiting man duties for various enslavers starting when he was quite young.[5] While there were far fewer enslaved waiting men than there were plantation workers, the position of a waiting man was documented in tax lists and runaway advertisements, and was growing more common among middling planters and urbanites.[6] As one of these many male domestics, Harry was quite likely skilled in a variety of tasks, whether that be grooming, tailoring, dressing, preparing and serving food, running errands, and delivering messages and other items, or any other task delegated to him.[7]

Crucially, waiting men would accompany their enslaver on their travels. For Harry, this meant the opportunity to familiarize himself with nearby states, as he traveled with Burnet to North Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee. Harry may well have used his knowledge of these areas, as well as his understanding of the travel customs around these parts, in order to escape from the Parker’s Ferry area, and venture northward.[8] Harry’s “good English” may have also supported his understanding of travel customs. Harry would have been able to speak with any White person he encountered on the road without suspicion, while also being able to code switch to speak with other Black travelers.

Harry could also “read and write a little.” South Carolina, like many southern states, had laws that forbade enslaved people from gaining an education. The Negro Act of 1740 prohibited enslaved people from learning to read or write, as these skills could not only show the intellectual equality of Black and White people, but also give enslaved people means of communicating and aiding both their own and one another’s escapes and resistance.[9] However, as Burnet’s “waiting man,” Harry was in a position where reading and writing would prove useful not only to himself, but to his enslaver. Harry, for example, could read any correspondence that Burnet received. While 1740 law explicitly prohibited the use of enslaved people as scribes, Harry could also write letters back in the name of Burnet, as well as notes, lists, or anything else useful to his enslaver.[10] South Carolina’s anti-literacy statute threatened enslavers with large fines which Burnet potentially risked in advertising Harry’s abilities.

By mid-April 1804, the advertisements seeking Harry’s return appear to have stopped. We cannot know for sure why, or what had happened to him. It could be that he had been recaptured and returned to Burnet. Or perhaps Harry found employment somewhere he could be paid for the many skills he acquired as Burnet’s waiting man. The stories of the waiting men is not well known, but they deserve to be heard.[11] Regardless of Harry’s fate, his story sheds light on the role of enslaved male domestics in early American history. Even while enjoying a relatively privileged position and somewhat easier working conditions, they too yearned to be free.

View References

[1] Douglas Walter Bristol Jr., Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 11.

[2] Phillip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Chesapeake and Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 246.

[3] Samuel D. Gross, A System of Surgery: Pathological, Diagnostic, Therapeutic, and Operative (Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea, 1859), 559.

[4] William Grimes, Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave (New York, 1825), https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/grimes25/grimes25.html (accessed March 14, 2025).

[5] William Grimes, Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave (New York, 1825), https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/grimes25/grimes25.html (accessed March 14, 2025).

[6] Cathleene Hellier, telephone interview by Jennifer Santos, February 26th, 2025. Cathleene B Hellier, “The Waiting Man: Enslaved Male Domestics in Virginia, 1619-1800.” Order No. 27744633, The College of William and Mary, 2020.

[7] Phillip D. Morgan, Slave Counterpoint: Black Culture in the Chesapeake and Lowcountry (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 245-246.

[8] Cathleene Hellier, telephone interview by Jennifer Santos, February 26th, 2025.

[9] ” O’Neall, John Belton. The Negro Law of South Carolina. Columbia, SC: John G. Bowman, 1848. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/public/gdcmassbookdig/negrolawofsouthc00onea/negrolawofsouthc00onea.pdf (accessed March 14, 2025).

[10] Cathleene Hellier, telephone interview by Jennifer Santos, February 26th, 2025.

[11] Cathleene Hellier, telephone interview by Jennifer Santos, February 26th, 2025.