His enslavers called him Ishmael. Biblical references were omnipresent in this part of New England, and surely this was a familiar name to the devoutly religious population of southeastern Connecticut. For many Christians, Ishmael symbolized, “bondage to the flesh and the old covenant of Sinai.”[1] The name could thus denote a lineage of servitude and separation from God’s chosen people.

His enslaver, Reverend Eliphalet Adams, was a leading figure within the community of New London, Connecticut.[2] He seemed to have an affinity for the name Ishmael, previously enslaving another man whom he called by the same name. This Ishmael had died in 1729, a good three to four years before Ishmael Mux was born, ruling out the possibility that these two were father and son.[3] But English colonists often recycled names, and in New England in particular, the survival of forenames was important.[4] No record survives of Ishmael’s actual father. His mother was a mixed-race enslaved woman named Flora who gave birth to Ishmael when she was seventeen. After only three years with her son, Eliphalet sold Flora for one hundred pounds and had her sent out of New London, keeping her infant son for himself.[5]

Eliphalet baptized Ishmael two years later on a rainy Sunday in late October 1738. We can only imagine what the five-year old boy thought as he stood before a sparsely attended meeting of New London’s First Church of Christ.[6] Did that five-year-old boy understand or share the beliefs of the Black woman his enslaver also held in bondage named Phillis? On that day Phillis professed her faith, and “owned the covenant,” thereby gaining partial membership into the congregation. That Sunday Eliphalet baptized a total of five of people he enslaved: Ishmael along with Phillis and her three children, James, Ziba, and Sylvanus.[7] We will likely never know what kinds of connections existed between Ishmael and Phillis’ family. Perhaps after Eliphalet sold Ishmael’s mother he had charged Phillis and her husband James with some responsibility for raising Ishmael alongside their own children. By extending the sacrament of baptism to his enslaved servants, Eliphalet had claimed responsibility for their spiritual education. This reflected his own belief that everyone, including people of African or Indigenous descent, needed redemption. In his view,

whatever civil Priviledges accrew [sic] to us by our Birth, or whatever title we may have to the blessings of the Gospel Covenant by Virtue of our descent from such and such, yet it seems we are all alike as to this, that we are Polluted and defiled with Sin, and this shews that even Young Persons need Cleansing.[8]

Education was a key component of this belief and Eliphalet took responsibility for teaching Ishmael to read and write. Perhaps Ishmael learned his letters alongside Sylvanus, Ziba, and James.

Whatever Eliphalet thought of the souls of his servants, he had no interest in freeing their bodies. When he died in 1753, the executors of his will followed his instructions to divide his enslaved property — collectively valued at nearly one thousand pounds — evenly between his two eldest sons and his daughter. Ishmael, who was now around twenty years old, surely had no say in the family’s decision to bind him to Eliphalet’s second oldest son Pygan.[9] Pygan had followed in his father’s footsteps as a community leader, serving variously as a church deacon, militia officer, justice of the peace, administrator of New London’s lottery, and Assembly representative. He was a silversmith, a farmer, and an Atlantic merchant. Given how busy life kept Pygan, he undoubtedly appreciated inheriting Ishmael’s skills and labor power for himself. Ishmael’s literacy as well as his proficiency with numbers may have meant that he did more than arduous physical labor for Pygan, perhaps even providing clerical or similar assistance for his enslaver’s various business ventures.

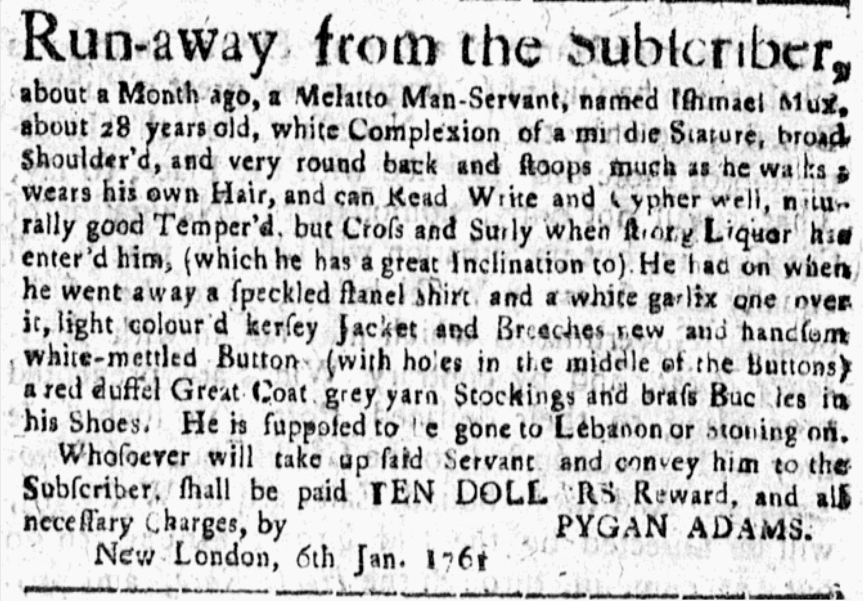

Ishmael escaped in early December 1760. Pygan seemed all too aware that Ishmael was capable of passing for White. In his advertisement he chose to mention that Ishmael “wears his own hair” rather than a wig – a descriptor generally only used in runaway advertisements to describe the natural hair of runaway White servants. Even more unusual was that Pygan Adams felt the need to emphasize the “white complexion” of someone he deemed a “melatto” man. While the “white complexion” of a person of African descent might sound like an oxymoron – a consequence of the contradictory logics of racial categories and White supremacy – what fluidity remained within hardening notions of racial difference surely worked to Ishmael’s advantage.[10]

Given the prominence of the Adams family, it is likely that Ishmael was also well-known in New London, and thus needed to escape the area if he was to remain free. Pygan’s hypothesis that he might flee to either Stonington or Lebanon made sense — Ishmael quite possibly had accompanied Eliphalet and later Pygan on their numerous trips to these two towns. But Lebanon surely offered the stronger pull. Twenty-five years earlier Reverend Eliphalet Adams had sold Ishmael’s mother Flora to Jonathan Trumbull, then a young twenty-seven-year-old West Indian merchant. Trumbull would go on to serve as governor of Connecticut during the American Revolution, but in 1736 he bought Ishmael’s mother with help from his father and had her brought to Lebanon. If Flora was still alive and bound to the Trumbull family, she would be found there. Perhaps not just Flora but other children, half-brothers or sisters to Ishmael, were also in and around Lebanon. If Flora or other family members were alive, it is more than possible that Ishmael had connected with them before. Perhaps the hope of rejoining them finally propelled Ishmael out of New London. Although largely hidden in surviving records, the resilience of the enslaved and their family connections could be a powerful force.

Ishmael had spent his entire life, more than a quarter-century, bound to various members of one of New London’s most devout families. His life had not been easy. A rounded back, conceivably the result of decades of physical labor or perhaps a physical disability from birth or his youth, caused Ishmael to hunch over as he walked. Alcohol was one of the few pain-relivers that would have been available to him. What Pygan viewed as Ishmael’s “great inclination” towards liquor was perhaps desperation for respite from his body’s aches and pains.[11] At the very least, alcohol offered momentary escapes from the psychological impact of enslavement, when he could drop his “good temper’d” facade. In the King James Bible, an angel of the lord tells Ishmael’s enslaved mother Hagar that her son was destined to be a “wilde man” whose “hand will be against every man, and every man’s hand against him.”[12] Had Ishmael heard or even read the story for himself, we can imagine the extent to which these lines resonated with him. But the twenty-eight-year-old man who we meet in this advertisement was ultimately so much more than his biblical name or his perceived vices. In escaping slavery and claiming his own freedom, Ishmael Mux demonstrated a determination to uproot a lineage of bondage.

View References

[1] David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1966) 85.

[2] Frances M. Caulkins, Memoir of the Rev. William Adams, of Dedham, Mass.: and of the Rev. Eliphalet Adams, of New London, Conn. (Cambridge, MA: Metcalf and Company, 1849) https://archive.org/details/memoirofrevwilli00caul/ [accessed May 27, 2025].

[3] Joshua Hempstead, “The Diary of Joshua Hempstead of New London, Connecticut, covering a period of forty-seven years, from September 1711, to November, 1758; containing valuable genealogical data relating to many New London families, references to the colonial wars, to the shipping and other matters of interest pertaining to the town and the times, with an account of a journey made by the writer from New London to Maryland,” (New London, Conn: The New London County Historical Society, 1901). https://archive.org/details/diaryofjoshuahem1901hemp/page/n9/mode/2up [accessed May 27, 2025].

[4] Robert M. Taylor Jr. and Ralph J. Crandall, Generations and Change: Genealogical Perspectives in Social History (Macon, 1986), 223.

[5] For bill of sale see, “Bill of sale or indenture made by Eliphalet Adams of New London, Conn to Joseph and Jonathan Trumbull of Lebanon, Conn” May 12, 1736. Connecticut State Archives (MV 326 Ad15) Joshua Hempstead, noted that Ishmael’s Mux’s mother’s name was “Florio” which is almost certainly the “Flora”, the woman Eliphalet Adams sold in 1736. See Hempstead, Diary, 341.

[6] New London Connecticut. First Church of Christ Records, 1670-1758. Hartford. Connecticut State Library, 1935. I, 158. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSK9-595V-8?cat=24394&i=81&lang=en [accessed May 27, 2025]. On the rainy weather that day and the slim attendance, see Hempstead, Diary, 341.

[7] S. Leroy Blake, The Later History of the First Church of Christ, New London, Conn (New London: Press of the Day Publishing Company, 1900) 71. See also Joshua Hempstead, Diary, 341.

[8] Eliphalet Adams, A brief discourse as it was delivered Feb. 6th. 1726,7 to a society of young men, in New-London: who by mutual agreement do meet together every Lords-Day-evening for religious purposes. By Eliphalet Adams, M.A. [Ten lines of Scripture texts] (New London, Connecticut: Printed & sold by T. Green,, 1727) Readex: Early American Imprints, Series I: Evans. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.ezproxy.library.wisc.edu/apps/readex/doc?p=EVAN&docref=image/v2%3A0F2B1FCB879B099B%40EAIX-0F2FD418CE602918%40-0FE66FE152D6EFE0%405 [accessed May 27, 2025].

[9] “Probate Packets, A-Ames, S, 1675-1850,” Probate Files Collection, Early to 1880 (Connecticut State Library (Hartford, Connecticut); New London, Connecticut). The only other enslaved person we know from the Adams household was a young boy named Polag, who Eliphalet willed to his wife, Elizabeth.

[10] Sharon Block, Colonial Complexions: Race and Bodies in Eighteenth-Century America (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) 60-62. Block uses this advertisement for Ishmael Mux to illustrate the complex dimensions of racial categories in early America.

[11] This was true of George Washington’s enslaved manservant William Lee. See Douglass Egerton, Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) 3-14.

[12] Genesis 16:12 (King James Version).