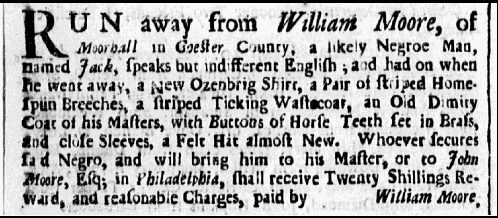

How might we today visualize the appearance of people who fled enslavement? How can we give faces to the supposedly faceless in history? The 18th-century clothing described in this advertisement can be reconstructed with some accuracy, as will be discussed below. It is more difficult to imagine their bodies, including their physical features, posture, hair style, attitudes, and the ways in which they presented themselves. We want to avoid having our own imaginings shaped by the racist degrading newspaper engravings of escapees printed with many advertisements. We also do not want to rely on eighteenth-century art since few White artists depicted Black Americans in a respectful fashion.[1]

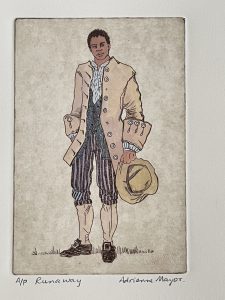

To help us form more realistic mental images we asked a modern artist, Adrienne Mayor, to imagine and sketch Jack, who took flight from enslavement during the summer of 1730. How may he have appeared? Viewers of Mayor’s drawing will judge for themselves, but this image of Jack is of a confident man who was courageous enough to risk his life to challenge the system of slavery itself. This Jack is far different from and certainly more accurate than the compliant, deferential humans that many enslavers deluded themselves into believing about the people they forcibly kept in bondage.

Jack spoke “indifferent English,” according to the 1730 advertisement, because he was born abroad. An advertisement published eight years later, in 1738, when Jack fled again, described him as having “Negro Country Marks” on his chest.[2] Many people in West African societies had their bodies modified by community elders as part of rituals associated with entering early adulthood.[3] Jack thus was almost surely born in Africa, captured, imprisoned, violently ripped away from his family and community, and eventually forced aboard a ship and endured the horrors of the Middle Passage to British America.

In 1730, Jack may have been relatively recently arrived in Pennsylvania, since the advertisement’s author apparently did not know him well; Moore described a few details of Jack’s clothes but none of his physical features. Like most newly arrived enslaved people, Jack struggled to adjust to White colonial culture. Wearing unfamiliar eighteenth-century colonial clothing and learning rudimentary English must have been difficult. Also like many of the enslaved, Jack probably clung, when possible, to traditions from his native country. He likely personalized his appearance, arranging his hair and modifying his wardrobe to reflect his African heritage.[4]

Jack was dressed in more valuable garments than most freedom seekers. As a relatively recent arrival in Pennsylvania, he received clothing from William Moore, including Moore’s old cotton coat with eye-catching “Horse Teeth” buttons, an “almost new” felt Hat, and a new shirt. During the eighteenth century, the material worn by most enslaved people was labelled “Negro cloth” and it was produced as inexpensively as possible.[5] The clothes, like Jack’s new “Ozinbrig” [osnaburg] shirt, were usually stiff, uncomfortable, and irritating to the skin. Very few freedom seekers wore any new clothes, although a good many took extra garments with them for warmth, to disguise themselves, and to sell to fund their break for freedom.

Unfortunately, Jack’s newer, fancier outfit made him more likely to be noticed and apprehended by constables and other Whites who wanted to claim a reward for his capture. Jack’s imperfect English and limited geographic knowledge of the area where he was enslaved also curtailed his chances for claiming permanent freedom. At some point, Jack was returned to William Moore. Undaunted, he escaped again in 1738.[6]

The labor of Jack and other enslaved people contributed to Moore’s wealth and growing prestige. At mid-century, Moore used workers, likely both free and unfree, to construct a magnificent mansion, Moore Hall, still standing today.[7] Moore was a long-time judge and wealthy member of the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly. He chose to support the British during the American Revolution. During the army’s encampment at Valley Forge in the brutal winter of 1778, More Hall served as headquarters for Colonel Clement Biddle of the Continental Army over the objections of William Moore.

Outdated conventional histories of the American Revolution often focused on White colonists who were portrayed as righteous rebels against British tyranny. Colonists like Moore, however, opposed the American Revolution and its promises of liberation. In particular, Moore opposed freedom for enslaved people he exploited for his own material gain. Today, people like Jack can be understood as seeking personal liberty, while men like Moore opposed freedom for anyone not part of the small group of privileged men he represented.

View References

[1] One exception is an image created the American painter John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark (1778), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; https://collections.mfa.org/objects/30998 (accessed 24 March, 2024).

[2] “Ran-Away from Wm Moore,” American Weekly Mercury, February 28, 1738.

[3] P.E. Lovejoy, “Scarification and the Loss of History in the African Diaspora,” in A. Apter and L. Derby, eds., Activating the Past: History and Memory in the Black Atlantic World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010); Michael A. Gomez, Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 39-42, 97-98, 121-124, 140, 175; Megan Vaughan, “Scarification in Africa: Re-Reading Colonial Evidence,” Cultural and Social History, 4, 3 (2007), 385-400.

[4] See the descriptions provided by Shane White and Graham White, “Slave Clothing and African-American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” Past & Present, 148 (1995), 149–86; and Shane White and Graham White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” The Journal of Southern History, 61 (1995), 45–76.

[5] On cheap clothing sold as “Negro Cloth” see “Just Imported from London,” American Weekly Mercury, January 27, 1743.

[6] “Ran-Away from Wm Moore,” American Weekly Mercury, February 28, 1738.

[7] William Moore House, Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/pa0306/ (accessed 24 March 2024).