It is a misty morning and the clouds roll over the hilly battlefield. James Williams rides upon a gray horse carrying a brass drum engraved with the silver emblem of the British 4th Dragoons.[1] Besides Williams, his fellow Black drummers ride in strict formation on gray horses, clutching their drums with cold hands. In the distance, the outline of the enemy can be seen through the heavy fog. Commander Sir Robert Riche stares through the haze and signals the drummers to await his command.[2] All is silent: one, two, three…The signal comes, and Williams brings his drumsticks down, beating out a powerful march. The battle has begun.[3]

This was the life that James Williams, also known as Lithgow, hoped to achieve: a life of freedom and independence alongside his fellow black drummers. Unlike John Blanke, a 17th-century trumpeter who appeared to be a lone Black musician in a mostly white Tudor court, Williams would not have been an isolated Black musician but belonged to a predominantly Black drumming unit.[4] But before he attempted to join up, James Williams had been enslaved, most recently as a sailor under Isaac Younghusband. However, this “cunning and designing individual” had escaped and planned a whole new life for himself, joining the British 4th Dragoons at the beginning of the Seven Years’ War.[5]

Isaac Younghusband was probably born in Virginia, and he had married Mary Pleasant (after whom he likely named his ship the Pleasant).[6] The name Isaac Younghusband appears numerous times in Virginian records, including Thomas Jefferson’s Memorandum Book entry in March 1775 recording his stop at “Mrs. Younghusband’s” tavern in Richmond.[7] It is likely that James Williams was born into slavery in North America. He may have been owned by more than one person, but by 1756 he was the property of Isaac Younghusband, and like other enslaved mariners he worked aboard ship and served his enslaver both aboard and on shore. Younghusband knew him as Lithgow, and James Williams was probably the name he took when he escaped from the Pleasant and joined the army as a free man.

What kind of life did James Williams hope to lead as a drummer in Sir Robert Riche’s 4th Dragoons? James Williams was likely in the army for only a matter of days or weeks before being re-enslaved under Younghusband. Despite his short time in the army, Williams would most likely have talked with other Black drummers in the regiment and learned about life as a drummer in the 4th Dragoons. The 4th Dragoons, founded in 1685 after the Monmouth rebellion, fought in critical battles across Europe including the 1715 Jacobite uprising, the Flanders campaign and the Seven Years’ War.[8] As a drummer, Williams would have worn a standard uniform that included a striped coat, a tassel hat, and engraved brass drums.[9] Although one might expect that a drummer was only responsible for music, Williams’ daily routine would have included stoking the fire, cleaning camp, assisting the wounded, and even carrying arms if needed.[10] Drummers were also tasked with carrying out corporal punishment upon disobedient soldiers. Of course, a drummer’s most critical role was drumming since the drum beats could determine the fate of a battle. Williams’ fellow soldiers were responsible for understanding and responding to every drum beat. One drummer stated that the drum “was the very tongue and voice of the Commander” and that “Drums and their players were vital in carrying messages to and from the enemy camp, a role that gave them a special and ambiguous status.” Williams’ position as drummer would have allowed him independence and according to another drummer “a feeling that his percussive expertise had made a vital contribution to the day’s events.” Drumming gave a sense of purpose and community but most importantly it gave a Black man freedom and pay.[11]

The 4th Dragoons was unique since it had more Black drummers than any other regiment. A 1715 Scottish observer and a 1748 regiment inspection noted that “The Drummers are all Black.” What is even more significant is that pay sheets and records show that Black soldiers were trained and paid in the same way as other soldiers. Drummer John Brigade, “A Black of Riches Dragoons” served during the same time as Williams and was discharged in 1753 with rheumatism. Although Brigade and his family then disappeared from the records, he likely received a pension as a freeman like other discharged soldiers. In this way, Williams wouldn’t have been an isolated Black individual, but rather one member of a community of free Black drummers—some of whom, like him, had achieved freedom in Britain.[12]

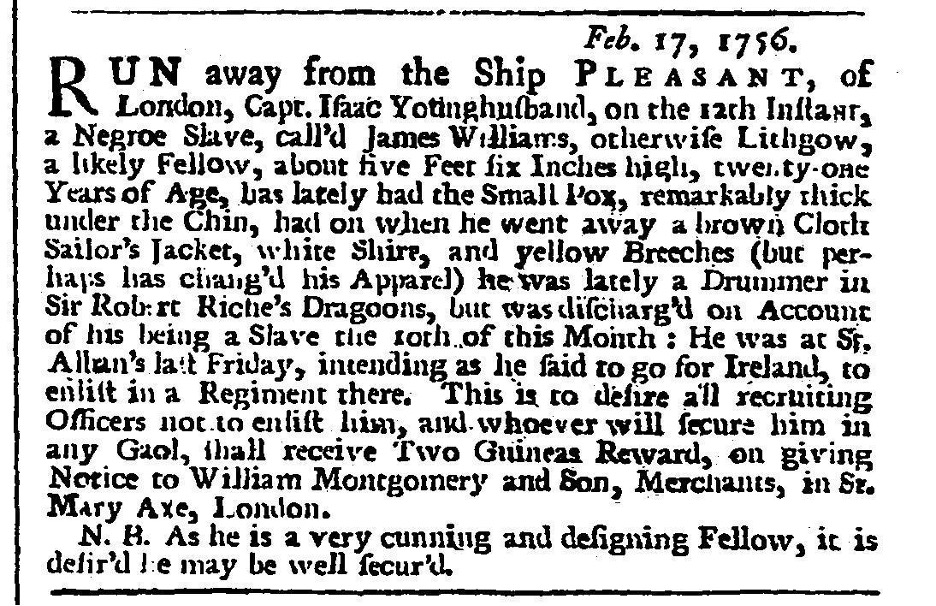

Somehow Younghusband discovered that Williams had joined the 4th Dragoons, and this led to Williams’ re-enslavement aboard Younghusband’s ship. However, Williams’ enslavement did not last long since he fled two days after being enslaved aboard the Pleasant. Although Williams’ exact relationship with Younghusband is unknown, it is clear that Williams was highly motivated to escape the Virginian captain and seek freedom elsewhere. Having enjoyed a brief period of freedom and discovered a possible new life and career in the military, Williams was not to be held back. He escaped again, prompting Younghusband’s advertisement in the London Evening Post on February 17th, which was repeated on February 23rd. Younghusband recounted how Williams had escaped before and joined the 4th Dragoons, had then been recovered by Younghusband and brought back aboard the Pleasant, but then two days later had escaped once again. The advertisement states that on February 10th, 1756, Williams was “discharged on account of his being a Slave” from the 4th Dragoons. The advertisement also states that two days later on February 12th Williams ran “away from the Ship Pleasant of London, Capt. Isaac Younghusband.”[13]

Within a matter of days or perhaps a couple of weeks, James Williams went from being an enslaved man from Virginia, to a free man serving in the army, to being re-enslaved, and then being free once again. Perhaps he was recaptured, and sailed back to Virginia on the Pleasant. But Younghusband’s advertisement suggests that Williams may have remained free this time. According to Younghusband, Williams had been seen “lurking about St. Alban’s,” some twenty-five miles from London, and “was intending to go for Ireland, and enlist in a Regiment there.”<[14] If this information was correct, then perhaps Williams had seen the potential of an exciting life in the army as a free man, and this time was venturing further away before he joined up, so as to avoid recapture. The year 1756 was significant as the start of the Seven Years’ War, a turbulent conflict that engaged European powers like Britain, Austria and France. If he made it to Ireland, Williams may have been able to join another British regiment to join the fight as a drummer. We may never know Williams’ fate, but this resourceful and determined young man had already proved he had the courage and determination to secure his freedom.[15]

View References

[1] Richard Cannon, Historical Record of the Third, or the King’s Own Regiment of Light Dragoons (London: Parker, Furnivall, & Parker, 1847), https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/50421 [accessed March 12, 2025].

[2] Cannon, Historical Record of the Third, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/50421 [accessed March 12, 2025].

[3] As this essay will show, James Williams likely served in the 4th Dragoons for a very short time before being re-enslaved, and so it is very unlikely he ever participated in military action with this regiment. But it is very possible that he did see service with a different regiment.

[4]Miranda Kaufmann, “John Blanke,” in Black Tudors: The Untold Story (London: Oneworld Publications, 2017), 7.

[5] “RUN away from the Ship PLEASANT… a Negroe Slave, call’d James Williams, otherwise Lithgow,” London Evening Post (London), 17 February 1756.

[6] “Isaac Younghusband.” WikiTree, 30 Mar. 2021, www.wikitree.com/wiki/Younghusband-132 [accessed March 12, 2025].

[7] Thomas Jefferson, entry for March 20, 1775, “Memorandum Books, 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/02-01-02-0009. [accessed March 12, 2025].

[8] “4th Queen’s Own Hussars,” National Army Museum, https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/4th-queens-own-hussars [accessed March 12, 2025].

[9] Cannon, Historical Record of the Third.

[10] Steven M. Baule, “Drummers in the British Army during the American Revolution,” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, No. 345, 86 (2008): 20-33.

[11] Christopher Marsh, “‘The Pride of Noise’: Drums and Their Repercussions in Early Modern England,” Early Music 39, no. 2 (April 21, 2011): 3, 5, 6.

[12] Cannon, Historical Record of the Third.

[13] “RUN away from the Ship PLEASAN,” London Evening Post, 17 February 1756.

[14] “RUN away from the Ship PLEASAN,” London Evening Post, 17 February 1756.

[15] Richard Hayes, “Irishmen in the Seven Years War,” Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review 32, no. 127 (September 1943), 4, 8.