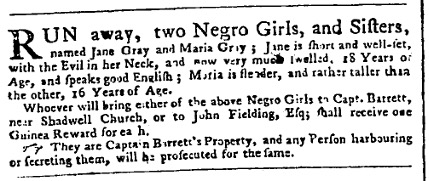

Sisters Jane and Maria Gray ran away from Captain Barrett’s residence near Shadwell church, Whitechapel some time before the 20th of November 1758. Parish records from St. Margaret’s church, Westminster (a parish about four miles across London from Captain Barrett’s in Shadwell) confirms that more than four months earlier Jane and Maria had been baptized, having learned the responses adults were required to know for the ceremony.[1]

Many enslaved individuals who found themselves on British soil believed that conversion to Christianity would release them from bondage. In essence, this was due largely to the Church of England’s emphasis on spiritual equality and liberation. This belief in conversion as a means of acquiring freedom was a consequence of the ill-defined legal status of the enslaved across Britain.[2]

On occasion, baptism appears to have brought with it a degree of formal protection and support from the parish, but what drew Jane and Maria to St Margaret’s? A significant number of Black baptisms (of both free and unfree individuals) were performed there by Dr. Thomas Wilson during his tenure (1753-84), including 20-year-old Olaudah Equiano in 1759.[3] Perhaps Jane and Maria knew one of St Margaret’s parishioners. Could it have been Ignatius Sancho who encouraged their bid for freedom?[4]

The sisters were not baptized together on the same day, maybe to avoid raising suspicions about their plans to flee in the months to come. Perhaps they were unable to leave the house together, as neither would be likely to attempt escape if it meant leaving the other enslaved and at risk of repercussions which might involve their return to the colonies and the harsh realities of plantation life.

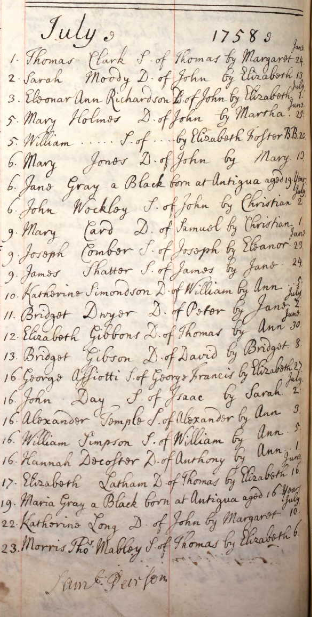

Jane was baptized on the 6th of July and Maria on the 19th. The record contains information that they provided themselves, so we discover not just their ages (19 and 16 respectively) but also that they were from Antigua, where they likely acquired the surname Gray.[5] The Gray family were well-known and influential on the island. Robert Gray’s will, dated 1754, stated that he owned and leased several plantations across the island, including one bought from John King in Belfast Division, possibly the same plantation later referred to as Gray’s Belfast.[6]

Were Jane and Maria named after the family that enslaved them, the plantation they resided on, or perhaps both? Were they purchased by the Gray family in Antigua or did their mother work on one of Gray’s plantations? Robert Gray had married Elizabeth Martin, daughter of Captain John Martin in 1737, in St. John’s parish, Antigua. Elizabeth had six surviving children when Robert died in 1760 Ann (b. 1744), Sarah (b. 1746), John (b. 1748), Elizabeth (b. 1750), Mary (b. 1754), and William (b. 1760). Robert’s daughters Ann (16), Sarah (14) and Elizabeth (10) were to each receive three enslaved individuals and £1000 as their inheritance.[7] Jane (b. 1739) and Maria (b. 1742) could potentially have grown up alongside these children on one of the Gray’s plantations in Antigua. Some of the enslaved female children of domestic servants in plantation houses were assigned as maids to the daughters and female relatives of plantation owners. If Jane and Maria had remained on Gray’s plantations, perhaps they would have found themselves among those inherited by Robert Gray’s daughters in 1760. His substantial estates were inherited by his eldest son John, who was only 12 at the time. John later married Rebecca Warner, who was the granddaughter of the Hon. Ashton Warner, Speaker of the House of Assembly in Antigua and Attorney General, who owned Clark’s Hill plantation. John and Rebecca named two of their daughters Jane and Maria.

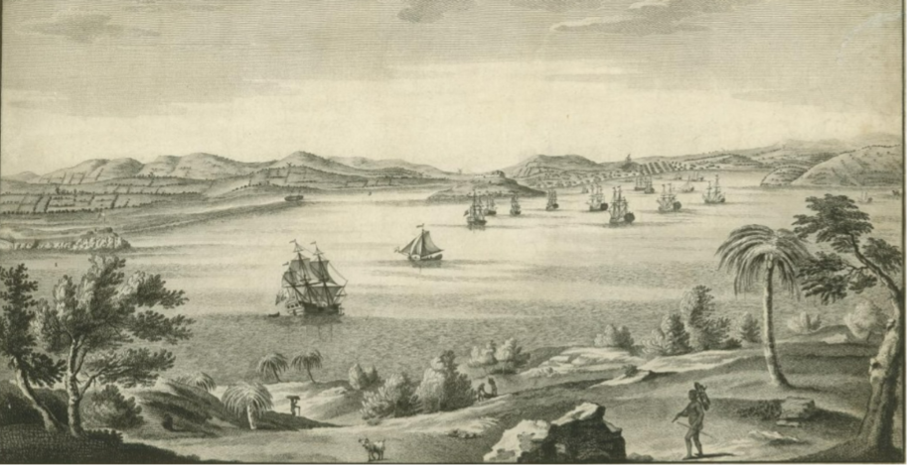

How then did the Freedom Seekers Jane and Maria Gray come to London? How did they become the property of Captain Barrett and crucially, how did they manage to stay together? Were they sold to Barrett in Antigua or in London, and if so, why? Had they accompanied female members of the Gray family from Antigua to England at some point? Perhaps on board a ship commanded by Captain Barrett? A Captain Barrett was listed in British newspapers as commander of the ship Friendship, which sailed between Antigua and London 1751-1758, as well as the Zephyr sailing the same route 1753-1757.[8] If this is the same Captain Barrett, then it is quite likely that Jane and Maria arrived in London on board one or the other ship.

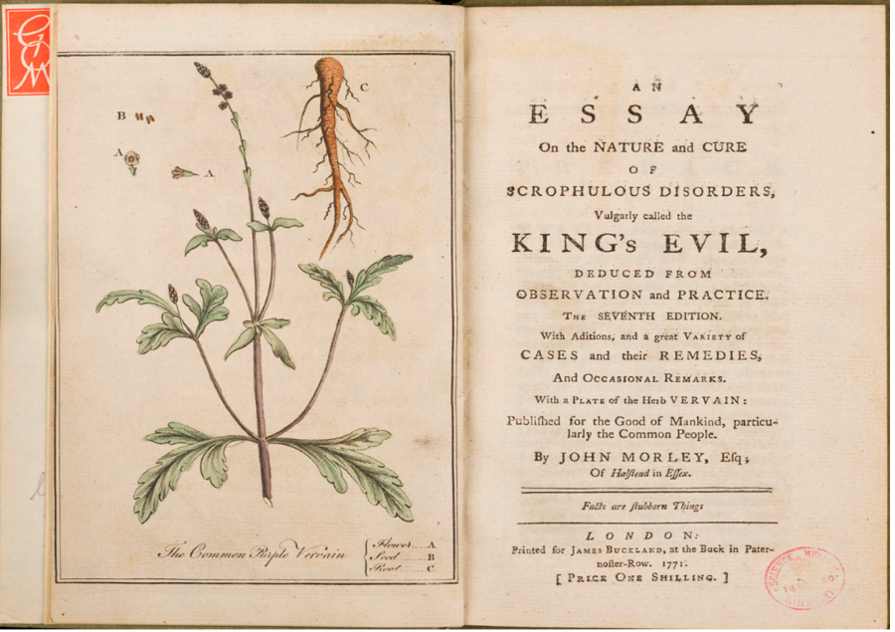

What was life in London like for the Gray sisters? The ‘evil in her neck’ that Jane suffered from is today known as Scrofula, which at the time was sometimes labelled the King’s Evil because of a popular belief that God had given kings the power to cure it by touch.[9] It is a form of tuberculosis that resulted in swollen lymph nodes and could cause horrific injury to the skin, particularly around the neck. The disease could prove fatal if it spread to the lungs and brain. Given how Jane’s swelling is described in the advertisement, her condition was perhaps becoming critical. Had they learned of a treatment known to some at this time, which used the root of the verbena plant as an anti-inflammatory? Did this motivate the sisters to escape before it was too late?[10]

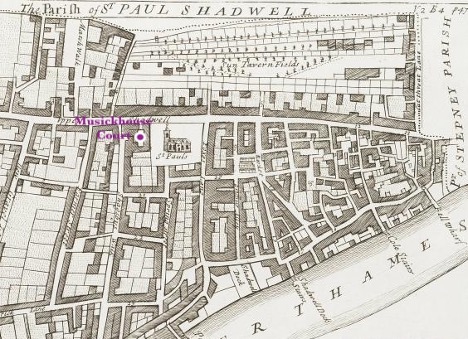

Shadwell was shaped by its proximity to the River Thames. A hub for individuals and industries serving the shipping trade, it was home to sea captains, sailors, dockworkers, ship-related tradesmen (chandlers, sailmakers, coopers, mast-makers), distillers, brewers, and biscuit bakers, alongside relatively affluent families and their free and unfree servants like Jane and Maria.[11] The newspaper advertisement placed by Captain Barrett in 1758 stated that he lived near the church. A map of Shadwell provided the names and locations of St Paul’s, the only church in the area (see map below). Land tax records confirm that in 1758 a Captain James Barrett lived in Musick House Court, just opposite the church, and had done so for several years. This is where Jane and Maria Gray lived and worked, and it was the location from which they escaped. In his will, proved in January 1761, Barrett mentions his ‘only son’ James who has not yet reached 21, and a daughter-in-law Mary (the widow of another son?) as the heirs to his estate.[12] It is likely that they also lived in Musick House Court.

What happened to the sisters? Did they find a place of safety and support in the parish of St Margaret’s, from Ignatius Sancho or other members of London’s growing and ever resourceful Black community? Though we can never be sure that their joint bid for freedom was successful, we can hope that they found themselves, for the first time, free to determine the course of their own lives.

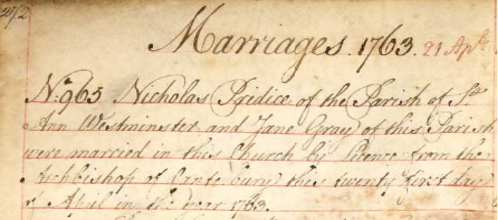

Parish records contain several references to women of the same name in London after 1758. These include a marriage record from St James’ Westminster between a Nicholas Pridice and a Jane Gray in 1763. However, this Jane Gray was not identified as Black, and the presence of a witness named Samuel Gray suggests she may have been White. Alternatively, perhaps Jane and Maria Gray were mixed race, and Jane was able to pass as White. It was relatively unusual for enslaved people to be identified with a surname, so it is possible that the name Gray indicated that these two young women were the daughters of an enslaved woman and a White planter named Gray.[14] Had Jane chosen to settle in London and integrate fully into the local community, and if so, was she still with her sister Maria? Did her husband protect Jane and Maria from discovery, recapture or kidnap? Did Jane and Maria ever discover that the threat of recapture was reduced given that Barrett died just a few years after they made their bid for freedom?

View References

[1] St. Margaret’s Church (Westminster, England), in “Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538–1934,” database, Ancestry.com (Lehi, UT), [accessed January 16, 2026]. For enslaved people’s views on baptism and freedom, see Simon P Newman, “Taken Not Given: The End of Slavery in Britain,” Law and History Review, 43 (2025), 739-770.

[2]“Baptism of Black Servants & Slaves,” Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York, https://www.york.ac.uk/borthwick/holdings/research-guides/race/black-baptisms/ [accessed January 16, 2026].

[3] “Thomas Wilson,” St. Stephen Walbrook, https://www.ststephenwalbrook.net/thomas-wilson [accessed January 16, 2026].

[4] Charles Ignatius Sancho was a resident of this parish. He was married at St Margarets in December 1758, all his children were baptized there and remained in the parish until his death. Ed. Rory Lalwan, Sources for Black & Asian History at the City of Westminster Archives Centre (London: Westminster City Archives, 2005)

[5] St. Margaret’s Church (Westminster, England), in “Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538–1934,” database, Ancestry.com (Lehi, UT), [accessed January 16, 2026].

[6] Vere Langford Oliver, The history of the island of Antigua, one of the Leeward Caribbees in the West Indies, from the first settlement in 1635 to the present time, Vol. 2 (London: Mitchell and Hughes, 1896) 34; “Gray’s Belfast/Lambert Hall,” Antigua Sugar Mills – A Griot Institute Project, https://sugarmills.blogs.bucknell.edu/grays-belfast/ [accessed January 16, 2026].

[7] Oliver, The history of the island of Antigua, 34.

[8] Derby Mercury (Derby, England) May 30, 1755; Leeds Intelligencer (Leeds, England) June 14, 1757; “Ships to and from Antigua 1752 – 1858,” West Indies Philatelic Study Group, https://wipsg.org/wp-content/uploads/Publications_WIPSG/Extracts/Publication_BWI_TudwayShipsAndCaptains.pdf [accessed January 16, 2026].

[9] “The King’s Evil and the Tradition of Touch Coins,” The Royal Mint, https://www.royalmint.com/stories/collect/the-kings-evil-and-the-tradition-of-touch-coins/ [accessed January 16, 2026].

[10] John Morley esq. published an essay on treating scrofula in which he described inheriting a treatment centered around the use of the root of the verbena plant which has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. See John Morley, “An essay on the nature and cure of the king’s evil: deduced from observations and practice. The second edition: with an addition of remarkable cases of poor sufferers, cured by the author. …” Eighteenth Century Collections Online, University of Michigan Library Digital Collections, https://name.umdl.umich.edu/004773729.0001.000. [Accessed January 13, 2026]. The use of verbena root in poultice form or as a tincture for the treatment for Scrofula is thought to derive from India. See “Verbena officinalis (PROSEA),” https://plantuse.plantnet.org/en/Verbena_officinalis_(PROSEA) [accessed January 16, 2026].

[11] Enslaved individuals like Samuel Can, Anthony Shill, George Pompey and Cato who all resided in Shadwell. See entries in “The Database,” Runaway Slaves in Britain: bondage, freedom and race in the eighteenth century, https://www.runaways.gla.ac.uk/database/ [accessed January 16, 2026].

[12] James junior was living in Sarah Street, Shadwell in 1798 ironically on the same street as a Peter Gray. See Land Tax Redemption Records, Middlesex, The National Archives, IR 23/48. Will of James Barrett, Mariner of Saint Paul Shadwell, Middlesex, proved February 4, 1761, The National Archives, PROB 11/862/408 https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D474447 [accessed January 18, 2026]. Did Barrett’s son and daughter-in-law Mary also reside at Musick House Court? The National Archives; PROB 11/ 862.Captain Barrett took on an apprentice called Edward Cole in July 1756, who may also have resided in the Barrett household. Board of Stamps: Apprenticeship Books, City Registers, National Archives, IR1/ 20.

[13] Excerpt of map of Wapping and Shadwell in John Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster: Containing the Original Antiquity, Increase, Modern Estate and Government of Those Cities. Written at first in the Year MDXCVIII, By John Stow, Citizen and Native of London (London: for A. Churchill et al 1720), IV, 47, https://www.dhi.ac.uk/strype/figures.jsp [accessed January 16, 2026].

[14] Marriage record for Nicholas Pridice and Jane Gray, St James Westminster, 21 April 1763. Records of St James, Piccadilly, Westminster, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1935, accessed through ancestry.co.uk [accessed January 18, 2026].