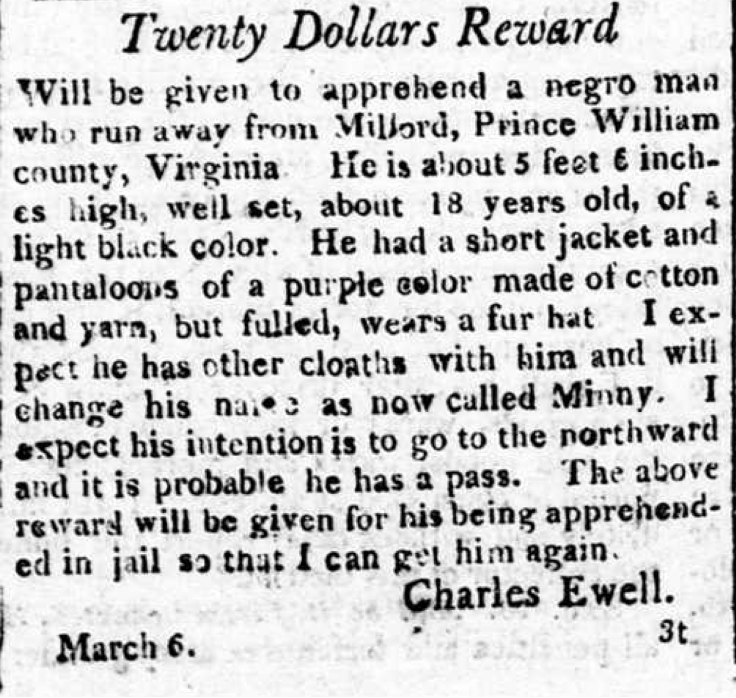

In 1811, a young enslaved man by the name of Minny absconded from Milford, Prince William County, Virginia, presumably heading North to freedom. The earliest advertisement for his capture was submitted to the editor of the Alexandria Daily Gazette on March 6th, 1811, likely by Revolutionary War veteran Major Charles Ewell. Another set of advertisements were published by late April of the same year, this time in the Washingtonian, with additional information: Minny “has been accustomed to drive a carriage, is a tolerable good cook and something of a gardener.”[1] Ewell was growing desperate and clearly believed Minny could have made it as far north as Washington DC.

While a city called Milford exists further South today, the location of his escape likely refers to Milford Mill, a grist mill owned by a Major Charles Ewell once resting near the modern town of Manassas.[2] Powered by a waterwheel and a loop in the rushing Broad Run, grist mills like Milford ground wheat and corn into flour both for local use and for export to foreign markets. Virginia’s transition from tobacco to wheat was well underway, incited by price changes in the European market and exacerbated by eroding Virginian soils; by 1803, Virginia farmers exported 100,000 barrels of wheat.[3] It is likely that enslaved people like Minny and his family, constituting over 20 percent of the Northern Virginia population, worked in constructing and maintaining the mill as well as the land around it and Charles’s estate.

The Ewell family had essentially built the Prince William settlement from the ground up.[4] By the time of Charles’s birth, they controlled large tracts of plantation land around the estate of Bel-Air, the family seat, built by Charles Ewell, the grandson of the Charles who most likely posted the advertisement.[5] Minny’s family may have lived and worked the conjoining Ewell properties, and he may have had experience traveling between plantations. His position may have given him a few advantages compared with enslaved tobacco field workers: Minny’s familiarity with driving may well have meant that he was regularly may have been tasked with taking the mill’s yield to port by carriage. About 20 miles from Milford was the port of Dumfries, and further north, an estuary opened into Washington, DC, connecting to the Potomac River and the Chesapeake. If he had obtained a legitimate pass instead of a forged one, transporting wheat from mill to market would be its most likely origin, and had he been routinely authorized to travel away from the plantation, he would have had ample familiarity with the route, guided by the Broad Run, to the Chesapeake watershed. An 18 year old boy in his prime with reasonable physical strength and plenty of practical skills might have found work under the captain of a Northbound, or even trans-Atlantic, ship.[6] His most likely destination would have been the nearby free city of Philadelphia, but in a post-Somerset world, he may have even left the colonies altogether for the free land across the sea.[7]

Minny ran with an assortment of garments, including “a short jacket and pantaloons of a purple color made of cotton and yarn, but fulled”.[8] Prior to the invention of aniline dyes in the mid-1850s, purple had garnered a reputation as the color of royalty and nobility due to its history of high cost. In classical antiquity, Tyrian purple was infamous for being produced at vast expense from thousands of tiny sea snails, and hence became the color of the imperial and priestly classes. The color no doubt still carried connotations of wealth.[9] Similarly, the short jacket and pantaloons combination was a fashionable import from the courts of France: as the breeches of the 18th century fell out of favor, they were replaced by the longer, more fitted pantaloons; the short jacket likely referred to a cropped dress coat, which by the 1810s had receded in the front to a straight cut above the waist line, leaving a tail at the back.[10] Combined with his fur hat, Minny took with him quite the lavish wardrobe, which he may have bartered and sold along the way to fund his escape, or used to present himself as a free man rather than an enslaved freedom seeker.[11]

If Minny managed to remain free, the impending War of 1812 would have offered a perfect opportunity for freedom. As British warships advanced up Chesapeake Bay, enslaved people fled en masse, aided by the British, who sought to guide them by lighting lanterns at their ship masts to guide them in the dark, reuniting them with families, and assisting organized escapes for their friends and family, and even sending ashore armed guards.[12] As part of the campaign of 1814, warships heading North to take Washington DC raiding the Chesapeake Bay and the Potomac certainly would have intersected ports at Dumfries and Alexandria. If Minny was still in the area, running to the British and then leaving with them would have certainly been possible.

Despite their outward affluence, as described by Donald Pfanz, “like many Virginians the Ewells were land poor; that is, they owned large amounts of land but had little money.”[13] The Ewell family fortune had been in decline ever since the conclusion of the American Revolution, even the nearby family seat struggling after the death of Charles’s uncle, Jesse. Their situation had likely worsened in 1811: by November of 1818, the conjoining Milford property was being advertised for public sale by virtue of a deed of trust from Charles to one J. D. Simms[14], and by 1830, the year of his death, Charles had moved to McCracken County, Kentucky.[15] The building pressure of Ewell debt may have finally encouraged Minny to flee, especially if he was in danger of being sold. As Alan Taylor notes, “Slaves had an extra incentive to flee if they belonged to estates facing disruption by the master’s death and debts”.[16]

With this knowledge, under the combined providence of the fact that Charles may have been distracted by his family’s situation, and then the outbreak of war; Minny’s geographical knowledge based on his experience with travel, his proximity to the port of Dumfries, major waterways such as the Potomac, and the unguarded Pennsylvania border; and finally the confidence offered by his pass, one may be hopeful that Minny managed to eventually escape bondage. The number of advertisements published make clear that Minny was not quickly or easily recaptured, and it is possible that he was able to make a free life for himself.

View References

[1] “Twenty Dollars Reward”, The Washingtonian, May 7, 1811.

[2] Manassas is famed as the location of the 1st and 2nd Battles of Bull Run during the Civil War. Cain, Charlotte.”Milford Mill – the Lost Landmark.” Prince William Reliquary, Vol 4 (3), (July 2005): 49–55.

[3] A. Glenn Crothers, “Agricultural Improvement and Technological Innovation in a Slave Society: The Case of Early National Northern Virginia.” Agricultural History 75, no. 2 (2001): 135–67. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3744747.

[4] Famous Confederate general Richard Ewell hailed from the Ewell family in question. Pfanz, Donald C. 2000. Richard S. Ewell. Univ of North Carolina Press, 2.

[5] “Bel Air”, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service.

[6] Henry J Berkley, “The Port of Dumfries, Prince William Co., Va.” The William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 4, no. 2 (1924): 99–116. https://doi.org/10.2307/1921197.

[7] In 1772, the Somerset v. Stewart decision ruled that enslaved people could not be detained in England and sold back into slavery. Many interpreted the case as effectively ending slavery on British soil; enslaved Americans who fled to Britain were effectively free. See Van Gosse, “As a Nation, the English Are Our Friends: The Emergence of African American Politics in the British Atlantic World, 1772-1861.” The American Historical Review 113, no. 4 (2008): 1003–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30223242.

[8] “Twenty Dollars Reward,”Alexandria Daily Gazette, Commercial & Political, March 8, 1811.

[9] Grovier, Kelly. “Tyrian Purple: The Disgusting Origins of the Colour Purple,” February 24, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180801-tyrian-purple-the-regal-colour-taken-from-mollusc-mucus (accessed March 16, 2025).

[10] Franklin Harper, “1810-1819 | Fashion History Timeline,” Fashion History Timeline, n.d., https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1810-1819/ (accessed March 16, 2025).

[11] Shane White and Graham White,“Slave Clothing and African-American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.” Past & Present, no. 148 (1995): 149–86. http://www.jstor.org/stable/651051.

[12] Alan Taylor, The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013).

[13] Donald Pfanz, Richard S. Ewell (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2000) 7.

[14] “Public Sale”, Alexandria Daily Gazette, Commercial & Political, November 5, 1818.

[15] “1830 Will of Major Charles Ewell – McCracken County,” Kentucky Kindred Genealogy, https://kentuckykindredgenealogy.com/2021/08/03/1830-will-of-major-charles-ewell-mccracken-county/ (accessed March 16, 2025).

[16] Alan Taylor, The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2013), 254.