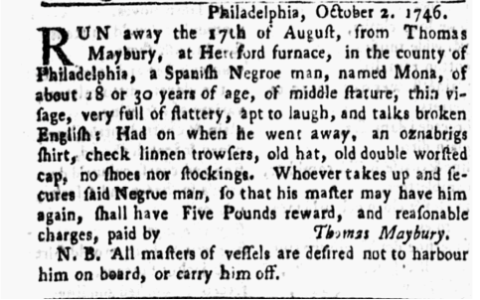

Mona ran away from Thomas Maybury’s property at Hereford Furnace in the County of Philadelphia on August 17, 1746. He is described as being “28 or 30 years of age, of middle stature, thin visage, very full of flattery, apt to laugh, and talks broken English.” His material circumstances, and the challenges he faced, were reflected in his clothing: an “oznabrigs” shirt, “check linen” trousers, an old hat, an old “double worsted cap,” and “no shoes nor stockings.” The runaway advertisement placed by Thomas Maybury offers a five-pound reward for his return and warns ship captains against aiding his escape. Labeled a “Spanish Negroe” by his enslavers, Mona escaped in 1746 from Hereford Furnace, defying the racist categorizations that denied his individuality and freedom. We can now use these words to piece together elements of his story—a life shaped by forced displacement and the brutal conditions of industrial enslavement.

While Mona’s precise origins are unknown, he appears to have been an African-descended person who had been enslaved in a Spanish-speaking colony. Because of this, he likely would have experienced different forms of enslavement and perhaps different work in Spanish colonies. He may have moved through various regions within the Spanish Americas, perhaps Central America, a Caribbean island, or even Florida, which was under Spanish control at the time, before arriving in Pennsylvania. Experiences such as these would have given him a very distinctive background, quite different from enslaved people born and raised in British North America. If his name had been shortened from Ramón to Mona, it was further evidence of his Spanish background and his move into British America.[1]

We can imagine what Mona may have experienced as having taken place within the broader context of imperial conflict and forced migration in the 18th-century Atlantic world. The War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739-1748), a conflict between Britain and Spain demonstrates the tensions over trade and colonial power at that time. Although the war officially began in 1739, British and Spanish ships had clashed for years, even during times of peace. One of the triggers for the war was Spain’s cancellation of the asiento, a contract that had allowed Britain to transport enslaved people from Africa and then sell them in Spanish America. The famous incident involving Captain Robert Jenkins, whose ear was cut off by Spanish coastguards in 1731, became a symbol of British grievances and helped stir support for war. During these conflicts, ships and cargo were seized, and people of African descent were often caught in the violence and forced into new forms of bondage. Mona may have been captured by British sailors from a Spanish ship, or perhaps he had been sold across imperial lines by enslavers. In either case, he appears to have lived under both Spanish and British colonial rule.[2]

Mona likely stood out as different. He may have spoken Spanish fluently, but as English was most likely his second language, he might not have spoken this as well as other enslaved people in Pennsylvania: the advertisement described his English as “broken.” The term “Spanish negro” further highlighted this difference, but it may also have suggested his experience of a different system of slavery. Coartación was one of these differences, a legal process whereby enslaved people could negotiate their own purchase price (and thus freedom), starting with a down payment and then paying off the remainder over a period of time. More people achieved freedom through coartación than by running away.[3] To Mona, the knowledge of coartación and the right to negotiate one’s own freedom may have shaped his understanding of enslavement as a legal construct rather than a permanent and unnegotiable state. This is one way in which he differed from the enslaved people around him in Pennsylvania, who likely had no knowledge of this legal process to secure freedom.[4]

Mona’s life in Pennsylvania was shaped by the ambitions and economic interests of the Maybury family, a family of iron-makers whose reach extended across Pennsylvania and New Jersey.[5] Enslaved by Thomas Maybury, Mona labored at Hereford Furnace, an ironworks established in 1745 in what is now Berks County.[6] At this time, furnaces relied on a variety of workers: African and American-born enslaved people owned by the furnace owners; enslaved people owned by others and hired by the furnace-owners; transported British felons, who were sentenced to work for a set period; indentured servants who worked for a set period in exchange for transport to America and their food and board; salaried free workers; and casual laborers.[7] As an enslaved ironworker owned by the furnace-owner, Mona would have likely encountered new ideas about time, work, gender, and even the skilled metal work itself.[8] In this context, with his growing knowledge of English, Mona may have steadily become acculturated to new space and people.

The Mayburys were deeply involved in the colonial iron industry, a field that required skilled labor and rigorous discipline. The iron industry was one of the most specialized and labor-intensive sectors in colonial America. Furnaces like Hereford required a skilled workforce to operate the massive bellows, manage the smelting process, and produce iron goods.[9] Enslaved ironworkers, though, were allowed relative freedom during off hours when enslavers didn’t control free time, home life, or leisure activities.[10] By working even more hours in the furnaces, beyond what was expected by the enslaver, enslaved people could make a very low wage. As Ronald Lewis wrote, “Overwork played an equally significant role in mitigating the debasement of the individual slave worker.” This money would have been just enough to minimally improve living standards with extra clothing or food.[11] Further, enslaved iron workers would be unable to leave their enslaver’s furnaces, unlike their free, wage-earning white counterparts. The Maybury family’s extensive involvement in iron production meant that Mona may have been familiar with multiple forges and furnaces beyond Hereford.[12] Before establishing Hereford Furnace, Thomas Maybury had built seven forges in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.[13] If Mona had knowledge of multiple forges, he may well have gained critical knowledge of the people and landscape of southeastern Pennsylvania and beyond. This knowledge could have played a crucial role in his decision to escape and in determining his possible route to freedom.

Thomas Maybury died unexpectedly in March of 1747, and his iron empire was thrown into temporary disarray. His children were minors, and the furnace and forge operations were left in limbo until his son William Maybury took control in around 1757.[14] During this period of disarray, the family may have been more concerned with the survival of their business than finding Mona, who they were still looking for on December 30th of 1746, more than four months after he had escaped.[15]

Mona was more than just a name in a runaway advertisement, and more than just a “Spanish Negro,” a term that reflects the painful realities of eighteenth-century racial designations. Today, we can use these words to understand a little of the man behind them, and how the life that he lived had been shaped by forced displacement. Throughout his life, he would have been exposed to and learned from a number of different world views, forming a perspective unique to him, all under conditions that sought to deny his humanity. Mona’s presence in the historical record, though limited, reveals a man who sought to transcend the constraints this label intended to impose, asserting his autonomy and humanity against overwhelming odds.

View References

[1] A similar claim was made about the possible change of a name from Domingo to Mingo in John Bezis-Selfa, Forging America: Ironworkers, Adventurers, and the Industrious Revolution (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018), 68. Ramon was a common name at the time, and Spanish nicknames of short names are taken from the second half of the name according to Margarita Espinosa Meneses, “De Alfonso a Poncho y de Esperanza a Lancha: los Hipocorísticos,” Razón y Palabra 21 (2001).

[2] Beatriz Carolina Peña, “Hilario Antonio Rodríguez: Un Spanish Negro de La Habana en la Nueva York Colonial,” Fronteras De La Historia, 25 no. 1 (2020), 46–74.

[3] Manuel Lucena Salmoral, “El derecho de coartación del esclavo en la América Española,” Revista de Indias 59, no. 216 (1999), esp. 358, 357–374.

[4] Peña, “Hilario Antonio Rodríguez,” 49.

[5] Pennsylvania Historical Society, Forges and Furnaces Collection, Collection 212, 34, 49, 61. Finding Aid available online at https://hsp.org/sites/default/files/legacy_files/migrated/findingaid212forgesandfurnaces.pdf [Last Accessed May 13, 2025]

[6] “Thomas Maybury, Blacksmith,” in “The Ironworker Mayburys of America,” Maybury Family genealogical site, https://www.mayburyfamily.com/the-ironworker-mayburys#1A We know the location of Mona’s enslavement from the advertisement for him published in the Gazette (Philadelphia), October 2, 1746.

[7] Bezis-Selfa, Forging America, 68.

[8] Ibid., 69.

[9] Ibid., 82.

[10] Ronald L. Lewis, Coal, Iron, and Slaves: Industrial Slavery in Maryland and Virginia, 1715–1865 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979), 147.

[11] Lewis, Coal, Iron, and Slaves, 148.

[12] Bezis-Selfa, Forging America, 79.

[13] Pennsylvania Historical Society, Forges and Furnaces Collection 212 Catalogue, 61.

[14] “Thomas Maybury, Blacksmith.”

[15] “Advertisement.” Pennsylvania Journal, or, Weekly Advertiser (Philadelphia), December 30, 1746.